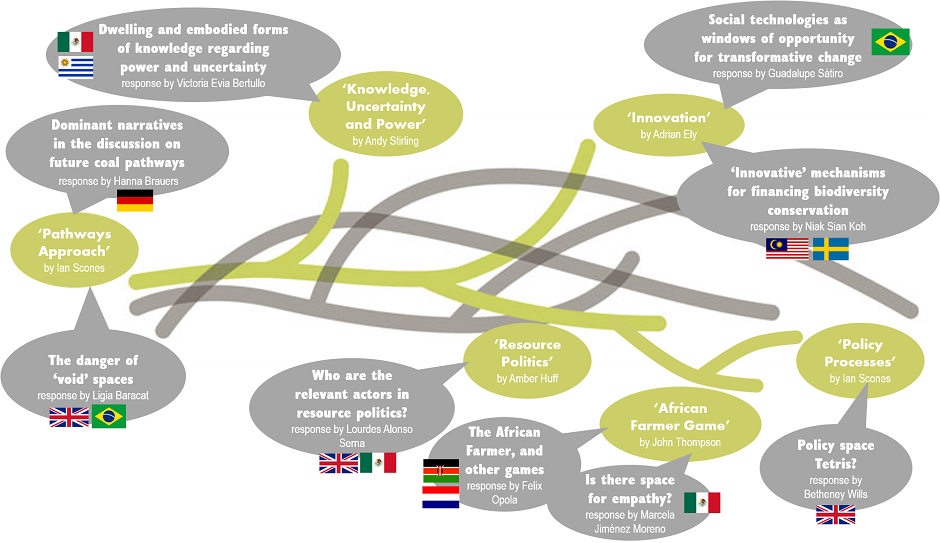

Following the STEPS Summer School in May 2018, this blog post is a conversation convened by three participants, Nimisha Agarwal, Ankita Rastogi and Jessica Cockburn. It includes introductions to the STEPS Centre’s ideas on six topics by STEPS researchers, and responses to each by different participants at the Summer School, drawing on their own knowledge and expertise.

The STEPS Summer School opened up discussions on ‘Pathways to Sustainability’ among 42 students from 25 countries. The call to participants during the Summer School was to incorporate multiple and diverse narratives (including non-mainstream ones) into research and practice. The STEPS approach is to maintain a plurality of alternatives while acknowledging the numerous framings and positionalities that these may emerge from.

While the participatory pedagogy was instrumental in getting these points across, there was a feeling among participants in the Summer School felt that at times the lived experiences and evidence from participants which corroborated or challenged dominant ‘pathways discourses’ were not adequately discussed.

A general point about path dependency leading to a ‘lock in’ was acknowledged. But concerns about the complexity that arises due to potential sustainability outcomes being bypassed by prior policy decisions were left hanging.

The obsession with quantification was rightly critiqued, but an alternative set of parameters to judge the success of a self-reinforcing strategy was left at vague value judgements (like the pathway has to be “just and safe”).

This raises critical questions of positionality and framing: which goal do we prioritize? And how do we deal with conflict in ideals such as democracy and sustainability? Since the conversation was started at the Summer School, and a lot of this “context-specific complexity” lingers, we decided to complete the loop and voice some of our contextual narratives in response to what has been presented in the discourse by researchers of the STEPS Centre.

Below we therefore present a series of ‘dialogues along plural pathways’. We do this by responding with evidence, narratives and possible practical applications from the experiences we as scholars have in the diverse contexts in which we live and work.

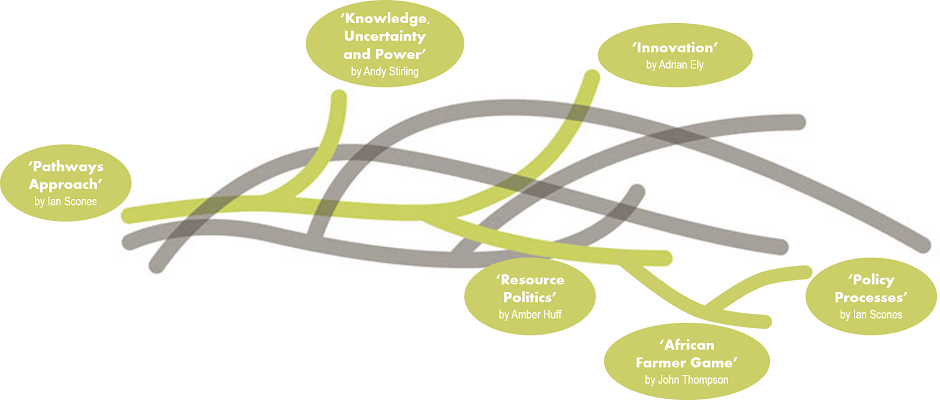

The blog is structured as a dialogue in which STEPS Centre researchers make a proposition around a key ‘thematic pathway’ as presented during classes at the Summer School, and scholars who participated in the Summer School provide a response.

The thematic pathways discussed here include ‘the Pathways Approach’, ‘Innovation’, ‘Knowledge, Uncertainty and Power’, ‘Policy Processes’, ‘Resource Politics’ and the ‘African Farmer Game’ – a way to understand some of these themes in a more interactive way through a simulation. We invite you to join the conversation and add your thoughts and comments below the blog. In recognition of the importance of positionality and ‘knowing where we come from’, we have provided biographies of all the authors below the article.

The Pathways Approach – by Ian Scoones

The STEPS pathways approach explores how social, technological, environmental pathways to sustainability are generated through an intensely negotiated political process occurring in complex, dynamic environments.

Pathways are constructed around narratives – storylines about the way the world is and its future – and so are deeply affected by underlying framings. Different actors have different framings, so depending on who you are and where you are located, sustainabilities will look very different and, with them, the pathways to get there.

A pathways approach is therefore attentive to power relations and how dominant pathways emerge, while other alternative, hidden pathways get silenced. Dominant pathways, associated with powerful public and private institutions, often promote a closed-down, controlling approach to transformations to sustainability, while alternative pathways may open-up to offer a more relational, caring approach.

Dominant narratives in the discussion on future coal pathways – a response by Hanna Brauers

The pathways approach provides a helpful tool to unpack complex dynamics of proposed futures – and how varying framings lead to very different, seemingly unavoidable, pathways.

To give an example, Germany has officially installed a commission to decide on a reduction of coal consumption to comply with the Paris Agreement. However, illustrating the power of framing, the commission has been called the commission on “growth, structural development and employment”. The words “coal”, “phase-out” or “climate” had no sufficiently powerful support to even be mentioned.

When the prospect of a coal phase-out is being framed by certain actors as detrimental for the regional economy and employment, while Germany’s emissions are small compared to e.g. China’s and India’s, it seems unreasonable to restrict coal consumption in Germany.

Narratives are used to create fears about electricity blackouts, a loss of a large numbers of jobs; and the competitiveness of the entire German industry. Other narratives are marginalised – for example about how a coal phase-out is crucial to reducing (local) air and water pollution levels; how it is important for preventing relocations of citizens and the destruction of forests and other natural habitats for new mines; or the effect on climate change.

The STEPS pathways approach can first of all help to unravel the underlying power relations. Secondly, it might be used to come up with alternative pathways, including a wider diversity of narratives and stakeholders’ positions, for a more honest discussion that goes beyond the climate vs. economy debate, finding more creative and caring solutions.

The danger of ‘void’ spaces – a response by Ligia Baracat

The STEPS pathways approach rightly calls for a ‘relational and caring approach’ to sustainable development. This is a reaction against the ‘closed-down, controlling approach’ often based on entrenched dualisms.

In the dualist logic, both ends – the ‘all ins’ and the ‘all outs’ – push and pull debate, and from the resulting polarisation, a new space emerges.

My concern is that this can often become a ‘void’ space. Instead of a creative, utopian space where alternatives are explored, as the pathways approach advocates, the newly created space is instead a mess of actors trying to understand which position – ‘all in’ or ‘all out’ – they feel it would benefit them to side with.

What is worse is that, in order to maximise such perceived benefits, we can often observe the most marginalised people in consensus with oppressive power structures and their dominant narratives. This, arguably, is a result of entanglement with funding streams. Local communities, NGOs and researchers alike find themselves weighing up the benefits of funding versus its downsides (the undesirable constraints or changes that it may demand from them).

Economic systems and interests have been instrumental in the erosion or annihilation of ‘alternative’ underlying framings over the course of history. The STEPS pathways approach must therefore also explicitly focus attention on the creation of alternative and pluralistic economic pathways – alongside social, technological and environmental ones – to be successful in turning ‘void’ spaces into truly ‘alternative’ ones.

Innovation – by adrian ely

Who determines what counts as innovation and what is excluded? This is a crucial question for the role that ‘innovation’ plays in pathways to sustainability.

Scholars from the economics of innovation (primarily in the ‘global North’) have traditionally focused on technological innovation that incorporates formal scientific knowledge, framing innovation as the point at which its application leads to an economic impact.

For example, manuals that guide the studies of the OECD and the EU define approaches to measuring particular characteristics of innovation systems. What gets measured is things like expenditure on formal research and development, outputs such as academic journal articles, patents or innovative activities within firms.

A key question for the ‘global South’ is: how relevant and applicable are these frameworks, in contexts that are very different to those in which they were developed?

‘Innovative’ mechanisms for financing biodiversity conservation? – a response by Niak Sian Koh

Limited funding is often highlighted as a major impediment in managing effective biodiversity conservation programs.

In order to scale up conservation funds, the Convention on Biological Diversity has highlighted some ‘innovative financial mechanisms’, which include Payment for ecosystem services and Biodiversity offsets. These financing mechanisms have emerged from policy discussions and institutions in the Global North (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, the World Bank Group), to be implemented in biodiversity-rich areas that predominantly exist in the Global South.

However, these ‘innovative mechanisms’ have posed social risks to the rights and livelihoods of indigenous peoples and local communities.

Biodiversity offsets, for instance, involves compensating biodiversity losses from infrastructure projects by conducting conservation activities somewhere else. On the Malaysian side of Borneo island, the Malua BioBank sells ‘rainforest credits’ to palm oil corporations and logging companies to offset their biodiversity losses. Each credit costs US$10 and represents 100m2 of protected rainforest.

Despite being hailed as an ‘environmental market solution for the green economy’, these conservation approaches can be exclusionary. Indigenous communities living around the offset area end up losing their access to nature.

The social risks of these ‘innovative mechanisms’ must be considered with respect to the local context they are being implemented in, whilst questioning who benefits and who loses out from these innovations.

Social technologies as windows of opportunity for transformative change – a response by Guadalupe Sátiro

The description of technology as a ‘social construct’ has helped to raise questions the supposed neutrality of science, and consequently of technology. And the emergent concept of ‘critical’ and ‘alternative technology’ has fed into growing concern about social and environmental issues.

The Social Technologies Network developed in Brazil, as a global South example, emphasizes the capacity of a collective to actively and successfully explore a new idea, resulting in a material and social product. This is in contrast to dominant narratives around innovation in which citizens are almost never drivers of innovation.

In this vein, the Social Innovation Movement around the world can involve the development of new processes, organizations and services to present incremental or even radical changes in the operating social context.

In Brazil, initiatives such as the Integrated and Sustainable Agroecological Production System (PAIS in Portuguese) reveal the potential to develop and expand agroecological practices and instruments to other similar contexts, in opposition to the dominance of agribusiness. Local initiatives are thus important sites of micropolitics for the achievement of sustainable development at multiple scales. The prospect of social practice and behaviour change in such innovative initiatives creates opportunities to link development, democracy and active citizenship.

Policy Processes – by ian scoones

Policy change does not occur in a linear, mechanistic fashion, despite what the textbooks suggest.

By understanding the practice of policy as a politically negotiated process involving multiple actors, we reject the idea of simple stages, artificial separations of facts and values, and an approach that separates policymaking from implementation. Policies may create, block or direct pathways, and so are essential in understanding how sustainability emerges, or doesn’t.

Accepting a non-linear, messy and political policy process, in any policy process – whether playing out at a very local level or in national or global arenas – we must look at three interacting questions.

- First, what discourses and narratives are being generated around a policy area: what problems are being defined, what expertise is being deployed and what solutions are suggested?

- Second, which actors and associated networks are involved, and how are they organised around particular policy narratives?

- And third, what politics and interests influence the outcome of policy processes through what means?

Analysing these three questions together helps identify which policy spaces are opened up and for whom, and which are closed down, and so helps us understand how policy changes, and how to change it.

Policy space Tetris? – a response by Betheney Wills

From all the sessions in the summer school, the session on policy process session was the one that most got me thinking about comparisons my PhD research (on UK marine natural resource governance).

The linear, mechanistic idea of policy process as depicted by the UK government in documents such as the Green Book Policy is shown to be created using rational choice via the ROAMEF cycle of Rationale, Objectives, Appraisal, Monitoring, Evaluation and Feedback.

However, as was reinforced at the Summer School, such a linear view can discount how political the policy process is, with values and priorities of some actors progressing over others. Currently in the UK there seems to be a drive to incorporate the ‘natural capital’ approach into the management of natural resources. Perhaps the economic roots of such a concept are allowing the approach to become the dominant pathway.

To me, the three interacting questions approach taken by STEPS is comparable to Kingdon’s model of policy streams, where the problem (agenda), policy (solution) and political (opportunity) streams align to open the policy window of change.

The Brexit process, as the UK leaves the EU, could be opening up different policy spaces or windows for change in the way marine resources are governed. If so, we need to ask: what change, and who will benefit from this?

Knowledge, Uncertainty and Power – by andy stirling

Despite many dimensions of acute difference between contrasting political settings around the world, a STEPS approach tries to cast light on some general patterns in relationships between different kinds of knowledges, uncertainties and power.

Interpretations of these patterns cannot be assumed, but must be constantly questioned. These interrogations can be done not only in ways that invite – or claim – ‘engagement’ in highly structured and codified ways, but also recognising that ‘participation’ is often most emancipatory when it is messy, unruly and uninvited.

Among these patterns, it’s clearly important not only to “speak truth to power”, but also to question how “power shapes truth”. Some of the most important ways in which different kinds of power work in the world, lie in the framing of what are held to be normative truths – about what is politically ‘right’. And this applies even more deeply to epistemic and ontological truths – about what it is that is ‘known’ about the world, and what are best ways of knowing.

Where prevailing power structures are successful in instilling the idea that there is just one ‘way forward’ with ‘no alternative’, then the resulting fatalism and despair can become their most oppressive assets. Across different sectors, this is the norm in much ‘development’ or ‘innovation’ policy around the world. Whatever the aims – for instance in support of social justice or climate change mitigation – uncompromising ‘no alternatives’ rhetorics often end up inadvertently favouring narrow incumbent interests.

This is why STEPS work bangs on so much about ‘opening up’. It recognises there is no shortage of powerful forces trying to engineer closures in knowledges and uncertainties.

What STEPS tries to do is to rebalance these wider power dynamics, by using contingent privilege to prise open greater political space in which marginalised interests can more directly act themselves.

It is in the resulting complex and diverse ways around the world, after all, that messy, unruly, uninvited emancipatory struggles have arguably achieved their most important gains.

Dwelling and embodied forms of knowledge regarding power and uncertainty – a response by Victoria Evia Bertullo

How do we question how power shapes truth? I agree with the standpoint that power informs our framing of what is ‘known’ about the world and what the best ways of knowing are.

I would like to reflect on this problem from my current research experience about the health and social impacts of massive pesticide usage in GMO soybean crop expansion in Uruguay.

The only aspect of the ‘technology package’ that is taken into consideration by the government risk assessment agency before approving a GMO event is released into the environment, is the GMO technology event itself. Other aspects of the “technology package”, which implies the use of huge amounts of pesticide that comes with them, are not taken into account. Even less are the everyday life experiences of people who work or live near the crops and have to experience frequent pesticide spraying.

“The soybean pesticide “smell” gives you allergies and headaches and you have to shut down on your house to prevent it from entering”; “The orchards are getting burned by the pesticide smell”; “Small animals, birds, bees and fishes are dying”; “People that work with those products for a long time are getting sick”.

Small farmers, agricultural workers and their wives and children are informed by their day to day lives in the territories they inhabit, and their dwelling and embodied forms of knowledge which arise from these. I think it is important to account seriously for these subaltern daily ways of knowing and a long term and deep ethnographic fieldwork is a way of approaching this.

By taking such an approach, I’m trying to open up a little bit the terms of the discussion of what is still unknown or uncertain about the GMO soybean expansion process in the Southern Cone, and which ways of knowing about it we are considering – and which ones we’re not.

Resource Politics – by amber huff

Resource politics – contestations and politics concerning access, use and control of resources – has leapt up policy debates on global development in recent years.

Powerful high-level narratives about growing food and energy scarcity and natural ‘limits’, together with concerns around international security and financial volatility, are influencing new policy configurations and powerful alliances between states, corporate capital, finance, researchers and environmental NGOs. Concepts and frameworks like the ‘Anthropocene’ and ‘planetary boundaries’ have increasingly become entangled with the rhetoric of sustainable growth and environmental management in ways that justify ‘top-down’ techno-bureaucratic and market-driven intervention as the ‘only option’ for responding to overlapping crises.

At the same time, critical research has highlighted the contested nature of dominant ‘global’ narratives on sustainability and crises, and has demonstrated many ways in which proposed ‘fixes’ such as market-driven climate mitigation, resource commodification and resource privatisation, even when part of ostensibly ‘community-led’ schemes, can intensify exclusionary relations of governance, accumulation and control at different scales.

Rather than effectively closing down opportunities for considering alternative and plural pathways and crucial justice concerns, we must develop and foster approaches that put politics – from political economy to the micro-politics of social difference – at the forefront of analyses of change.

In doing so, it’s important to take seriously the vernaculars of sustainability, security and justice that emerge from the particular histories, knowledges and experiences of people living in real-world settings who experience the social and environmental challenges and consequences of the ‘Anthropocene’ in their daily lives.

Who are the relevant actors in resource politics? – response by Lourdes Alonso Serna

This is a conversation I am really looking forward to having with all those interested in political ecology. Amber’s reflection on resource politics opens various entry points for a discussion around the forms of use, access and control of resources, and their intrinsically political nature.

In this proposition, Amber highlights the powerful alliances that shape market driven policies, and the role of critical research in unveiling the exclusionary relations of governance, accumulation and control.

I do not deny the significance of critical research, but what is missing here is the recognition of the actors that are affected by these policies. People affected, people who lose access to resources, people that oppose and fight. They are the ones that challenge the dominant narrative, they are the ones that produce any change.

Critical research is important because it frames (theoretically) these struggles, but most of the time, critical researchers don’t take an active part in these struggles.

The ‘African Farmer’ Game – by john thompson

Development of Africa’s smallholder agriculture sector and the introduction and application of new technologies and practices are critical for reducing rural poverty, improving economic growth and enhancing human welfare across the region. Yet there’s also a clear need for a new vision for agricultural development that can guide these efforts, while responding to the dynamics of agrarian change in Africa’s complex farming environments.

But whose vision should this be? How can risk and uncertainty be dealt with effectively? How can issues of gender, equity and social inclusion be taken into consideration in the design and implementation of these new initiatives? How should new investments in agricultural research and development be governed so that they benefit smallholder women and men farmers, who represent the vast majority of Africa’s agricultural producers?

The main aim of the African Farmer Game is to bring alive to players what life is like for a small farmer living in a rapidly changing, risk-prone environment. The simulation exercise demonstrates the complexity of decision-making, even in a simplified model of an agricultural society, and helps sensitise players to the impact of agrarian change from the producer’s point of view.

Of course, these experiences are not unique to Africa, as the life of small-scale producers throughout the world, both South and North, is characterised by uncertainty. All must navigate the vagaries of weather, pests and diseases and other chance events, coupled with unpredictable and volatile market supplies and prices, which create an environment in which decision-making is complex and ever-changing.

A key objective behind the African Farmer Game is therefore to increase players’ understanding of the sophistication of farmer decision-making under uncertainty. The game aims to help players appreciate the multiple trajectories which farmers may follow in their search for more sustainable livelihoods.

The African Farmer, and other games – a response by Felix Opola

In many parts of the world, smallholder farming systems have not ‘disappeared’ as earlier predicted. The complex decision-making process of a farming household depicted by the African Farmer game is often influenced by other ‘games’ that are being played elsewhere, where winners and losers are rarely well-defined, and where smallholder farmers hardly participate.

In the past decade, concepts such as inclusive growth, inclusive development and inclusive innovation have been used to refer to policies and practises that are aligned to the needs and interests of the marginalised. However, in agriculture for instance, the definition of ‘the marginalised’ has been elusive and there are as many interpretations as there are actors involved with varied backgrounds and interests.

How best smallholder farming can be supported is therefore a subject of debate. Market-based solutions are increasingly being recommended as more effective and financially sustainable ways of supporting ‘agricultural development’, compared to aid approaches, which are perceived to be a failure. But the ‘opening up’ of this pathway ‘closes down’ the role of the state, which is often crucial in the provision of public goods such as supporting the marginalised within a society.

Is there space for empathy? – a response by Marcela Jiménez Moreno

The African Farmer Game is a tool that without a doubt promotes empathy. For someone who has never had the opportunity to live and learn from rural families and small producers, it will surely be a revealing exercise that will influence the way they feel and think about sustainability issues in rural contexts. It is encouraging to think how this tool can help increase sensitivity among decision makers.

After participating in the game during the Summer School and while knowing that in many countries – in my case, Mexico – relevant decisions are still made in ways that vulnerability and marginalization of small farmers are being systematically reproduced or even accentuated, I couldn’t help but ask: are decision makers really unaware of the uncertainty faced by small farmers? Or even worse, do they know their situation and are systematically deciding not to change it?

I think the African Farmer Game, as part of the pathways approach, invites us to question the ways in which not only small farmers but different people make choices.

Under this approach, I would like to ask, in addition to the previous questions: how “broad” or how “narrow” is the space that decision-makers have in which to deliberate? And consequently, how many and which of them have the privilege to have a “wide and safe enough space” to bring empathy into major decision making? I am not justifying anyone, just trying to think about alternative questions.

Concluding thoughts on the dialogues

One of the key discussion threads of the Summer School was looking at ways in which sustainability can be approached in a plural, globalised world.

Over the years, economically driven technocratic models, developed in the global North, have gained significant traction. The STEPS Centre rightfully points out the need to open up pathways.

In this blog, we have continued these conversations as a means of sharing our understanding of the plural pathways that emerged from discussions in the 2018 Summer School with a wider audience.

During the Summer School, our conversations centred on opening up pathways to sustainability through the diverse interactions of society, technology and environment whilst recognising that these are complex process with the inherent ‘uncertainty’ of power relation and access to resources. The ‘Plural Pathways’ conversation which we have shared here brings forth the diversity of experiences and opinions from global south and global north, challenging, critiquing and acknowledging the understanding of these systemic power relations. Therefore it is an attempt to illustrate the diverse contexts in which the ‘thematic pathway’s of the pathways approach might play out, and to bridge the gap between dominant narratives and marginalised voices.

We hope to have illustrated that dominant and marginalised narratives are not at the polar ends of a binary line. Rather, we have sought to unpack somewhat the complexity and spectral nature of issues that emerge when working towards a sustainable future, keeping in mind equity among human beings and nature which we inhabit.

Author biographies

Nimisha Agarwal was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: My doctoral thesis deals with the subject of climate change from the perspective of rice and wheat farmers in Uttar Pradesh in northern India, focusing on different vulnerability zones. I examine how traditional knowledge systems and local methods/strategies are used by the farmers in dealing with climatic changes. My research work engages the specific issues in different vulnerability zones and shows how different social groups are impacted by climate change. My work presents material on farmer understandings of climate change, the problems they face and their reasons for opting for different strategies. Apart from formal work, my other interests include reading and working on queer and feminist practices, and bringing forth the same to discussions on marginality and sustainability.

Lourdes Alonso Serna was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She is a Postgraduate researcher at the University of Manchester. Her research title is ‘Harvesting the wind: the political ecology of wind energy in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca’. Lourdes has her Bachelor’s degree in International Relations, and a Master’s degree in Latin American Studies from UNAM, Mexico. Her research interests are political ecology, renewable transitions and uneven development.

Ligia Baracat was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: I recently returned to the UK after undertaking independent fieldwork in Acre, Brazil on the local-level effects of the global climate change mitigation policy, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD+). Here, I spent time with a number of indigenous communities and other actors working closely on the rights of indigenous peoples. Immersing myself in various, often conflicting views, about ‘development’ and REDD+ has led me to reflect on the decolonisation of knowledge production. I feel this is particularly relevant in the discussion surrounding Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC). I am a graduate in Social Anthropology from Aberdeen University, received my MA in the Social Anthropology of Development at SOAS and am currently putting together a proposal for PhD.

Hanna Brauers was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She is a research associate at the Workgroup for Infrastructure Policy (WIP) at TU Berlin and is a guest researcher at the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW Berlin). She holds a master degree in industrial engineering and management. In her PhD thesis she analyses the phase-out of coal and natural gas in Germany and Europe using a combination of economics and political science approaches with modelling exercises to enable the inclusion of stakeholder interests, power and inequality, as well as technological constraints in the analysis of the destructive part of the imminent post-carbon energy transition.

Jessica Cockburn was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: Working as a ‘pracademic’ in boundary spaces to better understand and transcend sustainability challenges really excites me. I recently graduated with my PhD in Environmental Science from Rhodes University (South Africa). In my PhD I applied a transdisciplinary research approach, engaging closely with practitioners in local NGOs who are facilitating stewardship in diverse multifunctional landscapes. This built on my previous experiences working as a practitioner in sustainable agriculture and catchment management. I also enjoy a glass of wine with friends, nature walks, cuddles with my husband and cat, or delving into a good book.

Guadalupe Sátiro was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She is a PhD student in Sustainable Development at the University of Brasilia, UnB. Her thesis is about the Social innovations for Sustainable Development with a comparative perspective between Brazil and UK. She holds a master degree in International Cooperation for Development and her topics of interests are development studies, pathways to sustainability, social innovation and social learning process.

Adrian Ely is the Head of Impact and Engagement at the STEPS Centre. His areas of interest include environmental impacts of GM crops, frameworks for biotechnology regulation, risk and uncertainty in policy-making around new technologies and innovation for sustainable development.

Victoria Evia Bertullo was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. I am a Uruguayan social anthropologist and I have a position as teaching assistant at the Department of Social Anthropology and on the Research Council of the Universidad de la República, Uruguay. Since September 2015 I have been studying for my PhD in Anthropology at the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS) in Mexico City. My main topics of academic interest are critical medical anthropology, political ecology and CTS studies. My doctoral research is focus on pesticide use impact from OGM soybean agribusiness in Uruguay. Other than that, I like travelling, cycling and gardening.

Amber Huff is a Research Fellow of the STEPS Centre. She is a social anthropologist and political ecologist. Her primary areas of interest include resource politics, the production of social, environmental, and health policy, and the politics of indigeneity and autochthony in resource struggles. Her research projects have involved investigating relationships among environmental policy production and human health and wellbeing, and studying the economic, social-structural, clinical, and policy contexts of healthcare quality and access. She is interested in developing innovative methodological and analytic strategies for understanding relationships between policy processes and human wellbeing, and for understanding how people perceive, respond to, and cope with the dynamic processes of social and environmental change.

Marcela Jiménez Moreno was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: I’m a Mexican graduate student with degrees in geography and human ecology and I am currently in my second year of a PhD in Sustainability Science at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. My doctoral research project focuses on the outmigration of young people from the rural areas of central-eastern Mexico, and analyzes the effects that migration has on local food security and land-use change. My main academic interests are vulnerability and resilience to global environmental change, environmental dimensions of human migration and contemporary rural youth. I really enjoy hiking, reading, watching movies and dancing.

Niak Sian Koh was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She is currently a PhD student in Sustainability Science at the Stockholm Resilience Centre. With a background in business management, sustainable development and a passion for biodiversity conservation, she bridges both areas through her work. Her research examines biodiversity offsets as a controversial financial instrument for compensating the ecological and social losses caused by infrastructure development projects. Her passions are volleyball, sea turtles and scuba diving.

Felix Opola was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. He says about himself: I’m a Kenyan PhD student at the Knowledge, Technology and Innovation Group, Wageningen University, currently based at the African Centre for Technology Studies, Kenya. My research focuses on the various discourses on inclusive innovation in Kenya’s agricultural sector and how these are implemented in practise. I have a background in sustainable development in agriculture (MSc) and food science and technology (BSc). I’m interested in a better understanding of the importance of innovation and technology in areas with resource scarcity such as the informal sector.

Ankita Rastogi was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: I am a doctoral candidate at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in Delhi, India. I work on waste recycling in Indian cities. Despite being born in Lucknow, my urban upbringing was fraught with gender and economic discrimination. My early exposure to classical art, literature and cinema provided an understanding of the feudal character of my nation. Waste recycling is just a sector that I use as an example of the persistence of it in “modernised” urban spaces. In pleasant weather I enjoy strolls through nature. Otherwise, listening to music indoors and completing my craftwork is fulfilling.

Ian Scoones is the Director of the STEPS Centre. He is an agricultural ecologist whose research links natural and social sciences, focusing on relationships between science and technology, local knowledge and livelihoods and the politics of agricultural, environment and development policy processes.

Andy Stirling is the Co-Director of the STEPS Centre. He trained in astrophysics, archaeology and anthropology, later working for Greenpeace International before research in technology policy. He focuses especially on questions over uncertainty, participation, diversity and sustainability in the governance of science and innovation.

John Thompson is a Research Fellow of the STEPS Centre. He is a resource geographer specialising in political ecology and governance of agri-food systems, community-based natural resource management and water-environment-health interactions. He is a research fellow at the Institute of Development Studies.

Betheney Wills was a participant of the STEPS Centre 2018 Summer School. She says about herself: I am currently in the first year of my PhD in the Sociology Department at the University of Surrey, Guildford (UK). My PhD is a case study investigating the governance structures and natural capital approach taken in the Marine Pioneer, a UK government pilot. My research interests are based around marine conservation, environmental policy and integration of local stakeholder knowledge. Out of the office, I am still drawn to the water, happiest on a beach, sea swimming or rowing as a member of my local club.