The question of how to improve farming to feed and sustain people in developing countries is as important as ever, and there are no easy solutions. One route to finding answers is through the science of agronomy – testing and evaluating how crops and farming techniques perform under different conditions. But, as with any science, there are battles and debates over what works, and even which problems agronomy should be trying to solve.

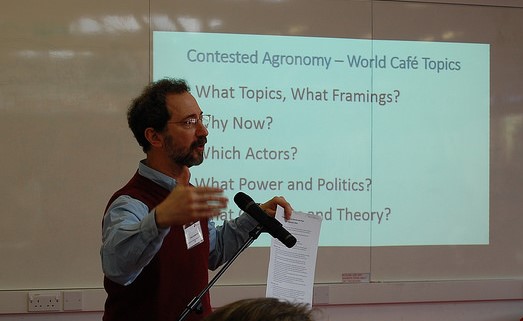

Whose agronomy counts? Is agronomy trying to solve the wrong problems? How can agronomy and the social sciences work together better to understand what happens to the science when it comes into contact with real farmers in the field? These were some of the key questions asked at the Contested Agronomy conference, which took place on 23-25 February at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS).

The event brought together over 80 participants from 18 countries to examine the politics of knowledge within the field of development-oriented agronomy (read more about the background & themes of the conference).

What is agronomy for?

On the first day, Bart Steenhuijsen Piters (KIT) asked “Will conventional agronomy ever reach the rural poor?” The answer, according to his reading of the literature, is that there was little evidence to suggest it will.

Much conventional agronomy focuses on intensification and increased production of food for markets. The rural poor often feature in proposals and disappear from evaluations. Remote rural areas are less and less prioritised by donors, and projects often take value chains and markets as their starting points.

Instead, suggested Steenhuijsen Piters, agronomy for rural poor people might focus more on the needs of households and individuals; nutrition and what they eat; trying to reduce the risks they face; the quality and remuneration of labour; and other factors like gender and young people’s skills.

Above all, he stressed the importance of not conflating ‘smallholders’ and the ‘rural poor’ or treating them as an undifferentiated bloc. Poor people’s views should be heard and included in the debate.

What – and who – is left out?

The story of agronomy is also a story of what gets neglected. Sieg Snapp (Michigan State University) talked about pigeonpea growing in East Africa, as an example of crops that are popular among some farmers, but under-researched. To illustrate this, Snapp showed a list of research projects where pigeonpea was initially included, then cut (watch the video of her talk here).

She showed the diversity of ways that farmers adapt and use pigeonpeas – from ratooning them to changing the time that the crop takes to mature, to using the thick stalks as cooking fuel. But pigeonpea was ‘always the bridesmaid, never the bride’, she said.

What questions does agronomy ask?

Other participants pointed out the need to reframe the fundamental questions being asked and who is asking the questions: whose knowledge and whose agronomy? As Ian Scoones (IDS/STEPS Centre) pointed out, if different groups, such as poorer farmers, were in the room, we would be asking different questions. To address these gaps, we need to talk to farmers and understand how they imagine their own, different futures.

Other participants pointed out the need to reframe the fundamental questions being asked and who is asking the questions: whose knowledge and whose agronomy? As Ian Scoones (IDS/STEPS Centre) pointed out, if different groups, such as poorer farmers, were in the room, we would be asking different questions. To address these gaps, we need to talk to farmers and understand how they imagine their own, different futures.

Ken Giller (Wageningen UR) pointed to the importance of healthy scientific debate, using the case of Conservation Agriculture. Though undoubtedly useful in some settings, this no-till technique has also been promoted by campaigners and donors in places where it is ineffective, he said. The way evidence was presented and promoted was undermining proper debate about the method. (Watch a video of Ken Giller’s talk.)

Listening to farmers

Much research – both in the South and North – does not take into account farmers’ viewpoints, according to Klara Fischer (Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences).

After a literature review of research on the social impacts of GM crops, out of 99 publications, Fischer found very little on farmers either in the literature about the north or the south: “farmers are at the bottom of the value chain”. Fischer also found a mismatch between the literature and the way the technology had been rolled out. Though the discourse in the literature on Africa was focused on how GM crops could increase production and yields, in fact the technologies commercialised to date have broadly been targeted at increasing the ease and convenience of farming, rather than raising yields.

The country most frequently studied in the GM literature is India, with Kenya, the UK and Germany also popping up in the titles, even though they don’t have commercial GM planting for food in those countries. Most research about the South is carried out by western researchers or researchers from the North – where many centres of agronomic research are based.

Challenging assumptions

Thomas Price from the Global Forum on Agricultural Research pointed out that we ignore these perspectives at our peril. He pointed to the assumptions that more agricultural production was necessary, that agri-food innovation and the “business of science” was required for a sustainable world. But, he said, when he was working in the Sahel the most important innovation wasn’t seeds, but the donkey cart. We need to look at the historical underpinnings of a place and the local context to inform the research, he said.

‘Transferring’ knowledge

This was an issue that cropped up in presentations on exporting China and Brazil’s agricultural know-how to Africa. Can China and Brazil use their home grown agricultural knowledge, which has driven phenomenal agricultural productivity at home, to transform agriculture in Africa? Lidia Cabral (Institute of Development Studies) gave an example of a Brazilian agronomist who had bought long-handled hoes for farmers in Mozambique to replace their ‘primitive’ short-handled tools, only to find that they broke them in half. He later realised that the farmers needed short handles so they could carry the hoes at the same time as babies, and other materials.

China, in its outreach to African agriculture, focuses on technological solutions that prioritise agricultural productivity and enhance growth. China has already established 23 agricultural demonstration centres in Africa, and more are planned. The agricultural demonstration centres are an example of “a top-down policy being implemented at the grassroots” says Xu Xiuli (China Agricultural University), who has developed case studies and research on four of the centres.

Agronomy in context

However, “context matters”, as Ian Scoones writes in a blog post reflecting on the conference : “‘agronomy’ had to be understood both as a technology and practice, which is always connected to social, cultural and political contexts. Agronomy is always mutually constructed, situated and relational.” The importance of context was a theme running throughout the conference.

Unfortunately, there is increasing pressure on agronomists to remove their studies from farm contexts and construct them as projects, often in short time scales. Scoones also wondered about the implications of the shift of agronomists from public to private sector institutions. Does this suggest a growing ‘commodification’ of agronomic knowledge, and if so, to what effect?

Finally, there are more sources of knowledge-technology, from different contexts, as part of the process of globalisation. All of these factors affect the context which agronomists and researchers and working in that shape agronomy and its contestation.

Opening up dialogue

Joshua Ramisch (University of Ottawa) said many of the participants at the conference were ‘interdisciplinary-curious’ – agronomists and social scientists keen to learn from each other’s insights.

Making agronomy work for poor farmers means taking seriously different forms of knowledge, technology and practice. It was clear from the discussion that the physical and social sciences could ask different questions about food, farming and rural futures. Events like the Contested Agronomy conference, by bringing together these different questions, could create a much-needed dialogue between the disciplines, which might better address the needs of farmers and rural economies in an increasingly complex and changing world.

Watch a series of videos, browse photos or look through presentations and posters from Contested Agronomy.

Contested Agronomy: Whose agronomy counts? was hosted by the Institute of Development Studies on 23-25 February 2016. It was supported by the ESRC STEPS Centre and hosted by the Institute of Development Studies, the Plant Production Systems Group, Wageningen University and the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT).

The conference built on an earlier workshop at IDS and the edited collection Contested Agronomy: Agricultural research in a changing world. Edited by James Sumberg and John Thompson and published by Routledge, it is part of the STEPS Pathways to Sustainability book series.

Comments are closed.