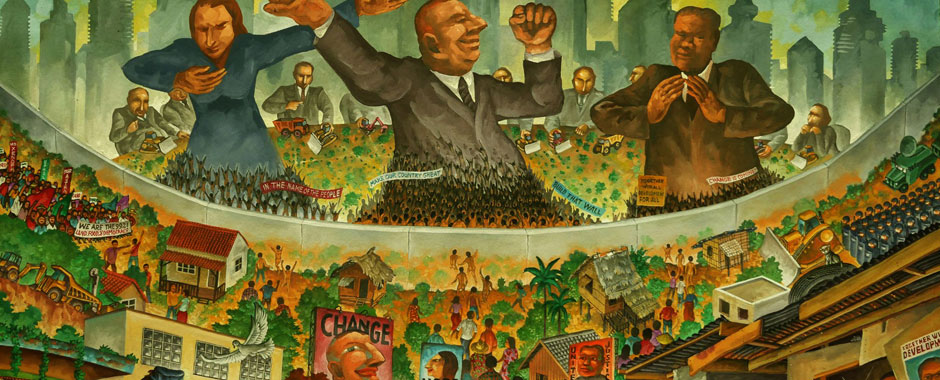

The last week has seen major gains for nationalist, populist parties in elections, both in Europe and India. Is this the end of the centre-ground consensus? What are the alternatives?

In India, the BJP swept to victory on the back of anti-Muslim rhetoric and Hindu nationalist slogans. Only Kerala stood out as a state where progressive politics resisted. In Europe, the picture was more mixed, but in France, Hungary, Italy, Poland and the UK, populist parties won, while in Germany a proto-fascist party won 10 percent of the vote.

Such parties rail against ‘elites’ and ‘outsiders’, notably migrants, and set a nation-first policy agenda seemingly against any forms of internationalism and globalisation. But who are their supporters? What are the connections to rural areas?

Authoritarian populism and the rural world

The rural roots of such regressive, populist movements have been the focus of research linked to the Emancipatory Rural Politics Initiative (ERPI) over the last couple of years. Yet, as we argued in the framing paper that kicked off the initiative, the rural dimension is frequently missed out in much contemporary commentary.

A major event last year gathered together researchers and activists to debate the issues. Emerging from this, a number of papers have been published in the Journal of Peasant Studies Forum on Authoritarian Populism and the Rural World. New papers (all currently open access) look at the US, Belarus, Hungary, Turkey, Spain, Russia, Bolivia and Ecuador…. and there are more in the pipeline.

Together, these papers demonstrate how the failure of neoliberal economic policies over the past decades has resulted in often extreme rural deprivation, combined with land and resource grabbing, and declining opportunities for young people in particular. A good overview from the Europe group in ERPI is offered by Natalia Mamanova. It is no wonder that populist politicians can easily enlist those who have been left behind. The dynamics are different across countries, of course, but the failure of the centrist consensus – what Nancy Fraser refers to as ‘progressive neoliberalism’ – is clear.

Whether it is the mainstream parties in the UK, the Indian National Congress or Macron’s En Marche, people do not see the jobs or livelihood opportunities being generated, and blaming migrants or minorities is an easy political win. Even when there’s a failure to create jobs or regenerate the countryside, as with Narendra Modi’s BJP over the past five years, nationalist-populist, religiously-inflected rhetoric seems able to deliver the votes, especially when a convincing alternative is absent.

Emancipatory alternatives?

So what of other alternatives that offer more hope, and tap into a more radical desire for economic and environmental transformation?

Across Europe, the Green parties had a good showing last week, committing to social justice, economic transformation and environmental policies. In Kerala, the Congress-led alliance won with commitments to poverty reduction and social welfare. Yet both were limited: the Greens won in urban areas, while Kerala is just one state.

Alternatives have to respond to real, lived, local problems, and, as we discussed at the ERPI conference last year – and shared in a number of short videos – there are many emergent examples of alternatives across the world that are creating new economies and generating sustainable alternatives. Whether these are experiments in food or energy sovereignty; new forms of mutual, collective economic regeneration; or commoning practices using new technologies that generate jobs and livelihoods, they all challenge the standard neoliberal recipe of austerity, efficiency and externally-led investment in rural areas.

Mobilising against right-wing populism

Too often, though, connections are not made between rural and urban efforts, between farmers and workers, between land-based and housing design initiatives. If isolated, the opportunities are missed for political mobilisation, based on new emancipatory narratives – what Chantal Mouffe calls left-populism. This is frequently the failing of the Green movement, seen too often as a privileged, urban, middle class concern; or indeed the Left more generally, with its roots in industrial unions.

Yet, taking a leaf from the right-wing populists and the Steve Bannon playbook that was well-rehearsed in Trump’s America, networking across potential supporters, linking diverse concerns, is essential. A great new paper from Jun Borras explains how mobilising alternatives in agrarian settings is tough, but not impossible.

The rural dimensions of creating emancipatory alternatives to both neoliberal capitalism and populist nationalism are essential. This is the case across the world. The elections this week are yet another wake-up call.

Further reading

- ERPI Framing paper

- JPS Forum (new series of articles)

- Open Democracy blog series

Video

- Open Democracy video series on authoritarian populism and the rural world