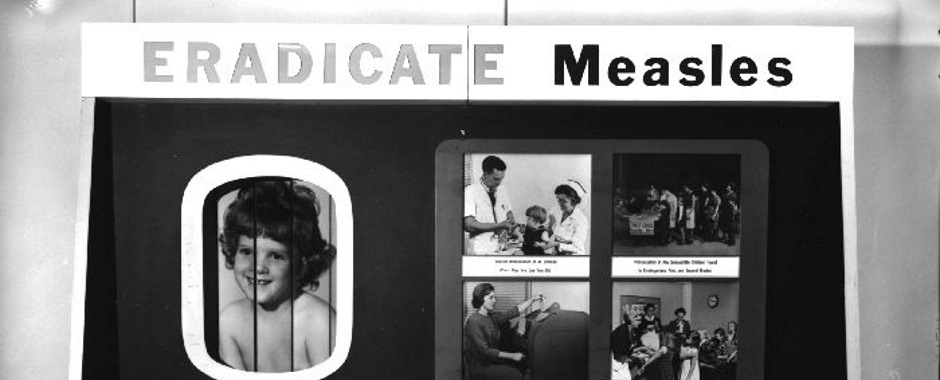

Measles and vaccines are back in the news. The UK has lost its measles-free status, according to Public Health England. The Guardian reports that about 30,000 children are starting primary school next month with no protection against measles, mumps and rubella, while 90,000 have had only the first of the two vaccines necessary for protection.

Why do people refuse the Measles, Mumps & Rubella (MMR) vaccine, and put their children (and others) at risk of serious illness or death? The old claims of links between MMR and autism generated by Andrew Wakefield, heavily reported at the time, are a big reference point. Even though these were discredited, their legacy still influences how some parents think about vaccines and the risks they seem to present. But there are lots of factors that affect the decisions that parents make about whether to vaccinate their children, and complicated social processes around these decisions.

As a public health measure, vaccines rely on mass public participation; even a few people refusing them undermines the project. So understanding why people refuse them is really crucial. Even so, it’s only one of many contributors to the decline in coverage for vaccinations – this report suggests a number of barriers, including difficulties for those with large families, people moving between health authorities, availability of appointments, literacy, shortage of time and access to health visitors.

Hesitancy and anxiety about vaccines is only one of many factors that might prevent people from using vaccines. But this can be made worse if people are not able to access the services that help to build relationships between health professionals and parents.

In their 2007 book Vaccine Anxieties, Melissa Leach and James Fairhead analyse fears about vaccines in the UK and West Africa, and the key ideas that people use to try to understand why people refuse them. These include ignorance & misunderstanding of science; risk and uncertainty; the role of trust; and the notions of rumour & resistance.

Risks are particularly interesting for the UK and MMR. A lot of effort is made in trying to persuade parents to take up vaccines by using facts and figures to stress the low risks of the vaccine to children; and the risks that refusing it present to a child and the wider population.

The success of this kind of communication depends on how parents interpret these risks and how they make decisions around them. Leach and Fairhead point out, for example, that parents’ decisions are not made in a single moment on a calculation of risk: rather they’re “dealt with by ongoing processes embedded in personal history, social relations and interactions, which may involve discussions among family members, peers or a wider community”. Online networks are mentioned in the book, but nowadays it’s likely that social media (especially Facebook) play a stronger role than ever in this dynamic. But the key point is that it’s hard to pinpoint a moment of ‘risk calculation’ where parents decide whether or not to vaccinate.

Risks are also often developed from statistics across a general population, grounded on “a view of an average person” – but people often don’t consider themselves as average. And the focus on risk overlooks the fact that people may not view these questions in terms of risk at all – there may be other ways that they ‘frame’ the problem that are stronger or more prominent in their minds.

Another dimension that isn’t always discussed is the way that people understand autism. From my own limited experience, conversations between parents after a diagnosis of autism are charged with emotion and personal stress; many parents are desperate to seek answers and ways forward to help their child flourish, despite patchy support. In search of practical advice, parents will often spend hours searching the internet or turn to online support groups – much easier and quicker to get than through official channels. Much of this advice and support will be helpful; some of it, including quack cures and ‘therapies’ for autism, will be downright harmful.

Parents have to sift through mountains of conflicting information to decide who to trust, and much bogus information is presented in reassuringly scientific language. The uncertainties about the causes of autism and the highly specific and diverse ways that it presents in children can lead parents to turn away from generic advice, and try a number of different ideas in search of something that works. This is a process that can take place over several years – creating difficulties for focused, time-limited public health campaigns. The doubts and anxieties formed in this process may easily feed back into parents’ groups where MMR and vaccination is discussed.

In the background of all of this is the problem of people’s trust in doctors and other experts in the news, and in the government more generally. Vaccine Anxieties, written in 2007, includes an observation that parents felt that their concerns had not been listened to and that the debate appeared to be a ‘battle’. Twelve years later, at a time of ever more diminishing trust and rising suspicion towards those in authority, it will not be easy for top-down approaches to communication to persuade parents to overcome their suspicion of the vaccines that keep us safe.

This article was posted as part of our 2019 theme on Uncertainty.

Uncertainties can make it hard to plan ahead. But recognising them can help to reveal new questions and choices. What kinds of uncertainty are there, why do they matter for sustainability, and what ideas, approaches and methods can help us to respond to them?

Uncertainties can make it hard to plan ahead. But recognising them can help to reveal new questions and choices. What kinds of uncertainty are there, why do they matter for sustainability, and what ideas, approaches and methods can help us to respond to them?

Find out more about our theme for 2019 on our Uncertainty theme page.