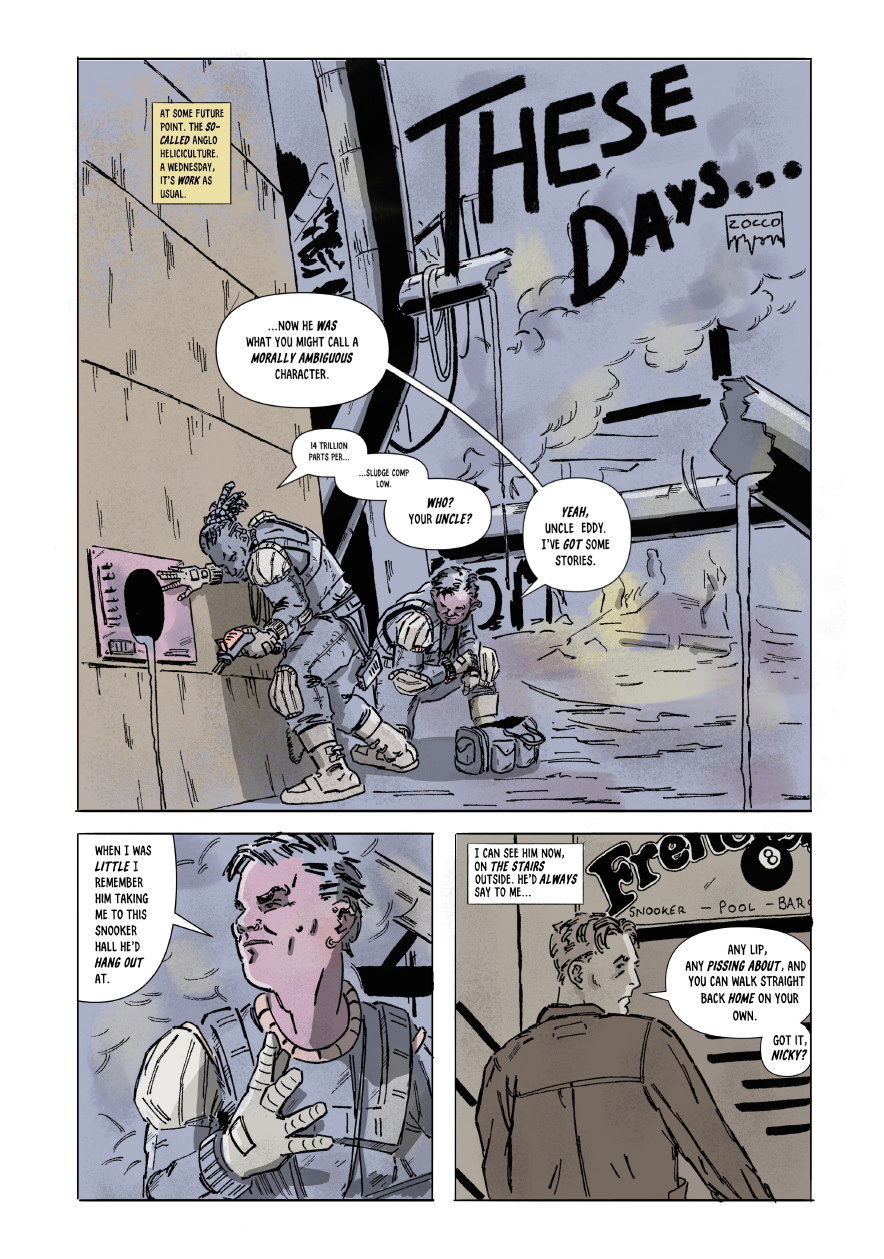

In our Natures theme for 2020, we are collaborating with the artist Tim Zocco. In the comic ‘These Days…’, a glimpse of a future age shaped by traumatic events, Zocco reflects on crisis, the difficulties of predicting radical change and thinking about what is to come. It’s the first in a series of creative responses to Natures, which will follow over the next few months.

Introduction

It was my last time in a pub before lockdown, I recall, when I started thinking about it. The full implications of coronavirus were coming into focus, we were in the Shakespeare’s Head and there was only one topic of conversation.

We all agreed that although its particular shape was unclear, a change was coming. If there was a gauze-thin membrane between normal life and one radically altered, we were passing through it.

This was all before a succession of calamitous mistakes taken by the UK government led to one of the largest death tolls in Europe (as of late May). But it still seemed obvious something big, an event, was taking place. It was a moment of crisis, a point of rupture between what had come before, and what would emerge after. It was rupture, public health, and the familiar calculation that weighs human lives against private profit.

That’s what had me thinking about the Lisbon Earthquake.

When it happened in late 1755, the earthquake sparked a fierce ideological war amongst competing sets of intellectuals. Those on one side, of a more conservative nature, sticking steadfastly to the faith based rationalism of the early enlightenment, and those on the other who began to question the wisdom and judgments of such beliefs. Emerging from this turmoil, Voltaire, firmly in the later camp, shook off the docility of Enlightenment Theodicy with the composition of Poem on the Lisbon Disaster (1755), a searing attack on the idea of Providence and a benevolent personal God. In the chaos of the Lisbon earthquake we begin to see people throwing off the magical thinking of innate hierarchy, and, along with the French Revolution, the moment helped to conceive the century that followed, and ultimately the Romantic philosophical tradition.

The Lisbon Earthquake was a moment of exogenous shock which radically altered the political and economic landscape, but it was not the sole parent of its effects. Like coronavirus today, the earthquake acted as an accelerant to the already existing tensions of its day. Precarious employment, wage volatility, and vast inequalities all exacerbated the trauma.

Our situation runs in parallel. The devastating consequences of coronavirus are further complicated by years of neoliberal policy, from austerity to precarious low-paid work. So as the world transforms around us, certainly beyond any one individual’s capacity to shape it, how are most of us going to recognise, understand, and contend with what it has become? Especially having spent so much of the time in isolated lockdown.

Above all, at least in the UK, there is the unmistakable class division between those on the front lines of the pandemic: hospital staff, shop-workers, gig economy professionals, whose experience is much deeper and more keenly felt then those, many in the professional and managerial classes, who have remained indoors. Of course, this does present the opportunity for some greater flourishing of working class consciousness, as the crisis exposes more and more the exploitative mechanisms of capital. But, for now at least, these mechanisms are kept safe by the prevailing ideology of neoliberalism and the myth of middle class exceptionalism.

It’s too early to say whether this disaster will transform the way that most people view human value and the structures of capital. But, in any case, for better or worse, the economy will be radically different, and those who service it will in turn be radically different too.

I can’t think about something like this without bringing to mind Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle – the old man who slept for 20 years, crucially, right through the American revolution. Or better yet, Kurt Vonnegut’s Billy Pilgrim, lost somewhere in time and memory, constantly emerging, slightly dazed, into new worlds and new continuities he doesn’t understand. An incomprehensible trauma breaking the backbone of time.

While any informed speculation on the future after coronavirus is probably beyond the power of this cartoonist (not least because I’m pessimistic about the further entrenchment of existing prejudices), I am interested in the idea of this Billy Pilgrim effect, with time out of joint, and negotiation determining our new collective reality. As Bifo puts it, coronavirus leaves us contemplating ‘A personal threshold of no more and not yet. But also a universal threshold of a mutation that is traversing the history of mankind. Enigmatically.’

Read the comic

Download the comic as a PDF or flipbook, or view it below (click on images for larger size).

Download (PDF, 11 MB) Flipbook version

Natures: Our theme for 2020

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

How is talk of crisis shaping nature and people’s views of it? How can colonial forms of knowledge, technology and power be challenged, and what might it mean to ‘decolonize’ the study of environmental change? What do alternatives look like, and how can we explore, nurture, imagine and live the relationships we might want for the future?