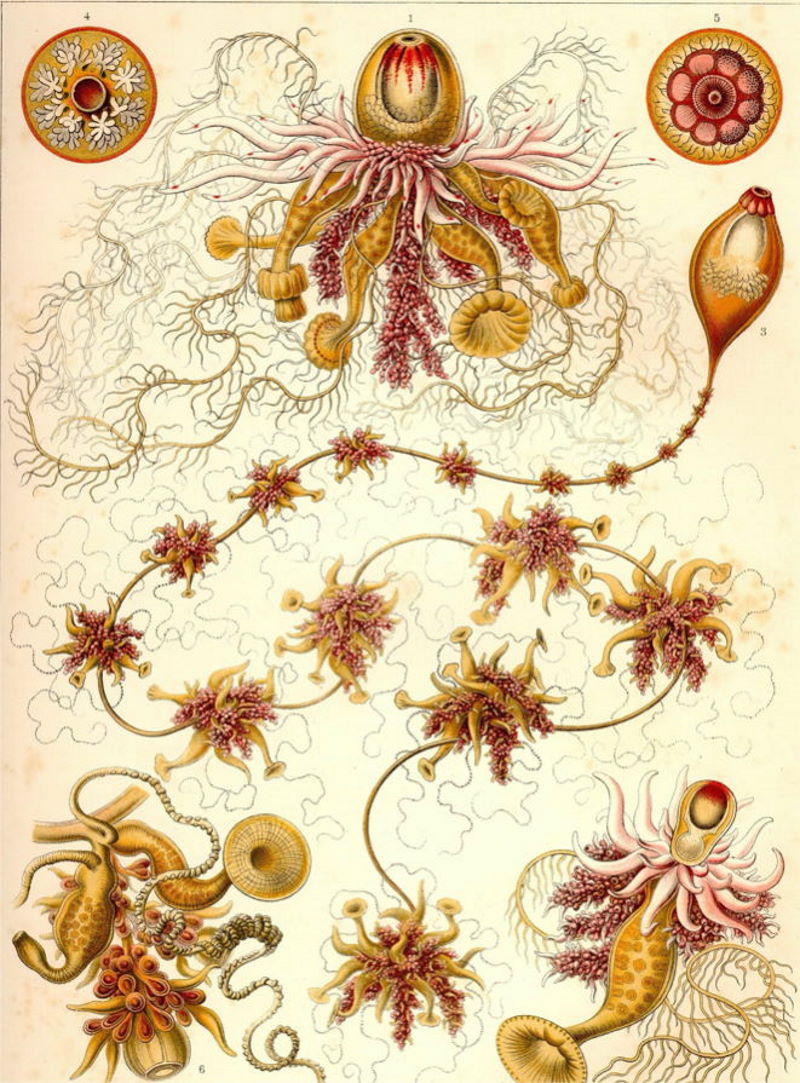

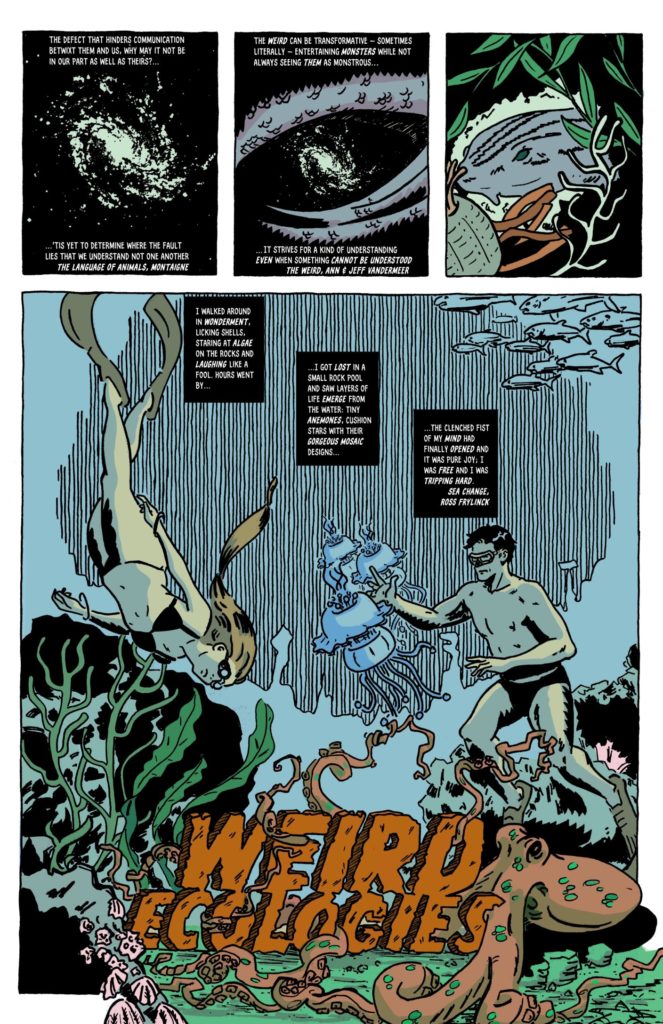

In this short post, Amber Huff (STEPS/IDS) and Adrian Nel (University of KwaZulu Natal) introduce the idea of ‘weird ecologies’ and explains why ‘the Weird’ has such an enduring appeal in culture and philosophy. The piece is followed by an original comic by Tim Zocco for the STEPS Natures year, a weird expedition into the undersea kelp forest explored by the Sea Change Project and beyond to chthonic monsters, alien ecologies, and ‘tentacular’ thinking.

The way many of us experience the effects of rapid globalization is that it has unsettled our ordinary perceptions of time, space, ecology, causality, and agency. Many who dwell in the so-called ‘Anthropocene’ “no longer find ourselves capable of believing in the innocence of the sensual world that surrounds us”. People often say that they feel dislocated and alienated from ‘nature’ and within society, despite our reality as natural and social beings.

The effects of globalization trouble distinctions between the real and the virtual; the actor, the action and the acted-upon; certainty and the margin of error. The result is disorientation and anxiety, as well as feelings of urgency and impotence, leaving some people despairingly passive and without the possibility of response. There are things out there and I know that they are real, but that I can’t see and can’t touch and can’t know ‘…and I don’t even know how much I don’t know about it. But it’s coming’. As Brad Tabas writes, the ‘world has become weird, our reality horrifying’.[1]

Can such a shared sense of disorientation in part explain the renaissance of ‘the Weird’ in recent years? ‘The Weird’ is seen in the proliferation of the elements and imagery of a liminal pulp literary genre in not only its ‘classic’ domains of fiction, film and visual art, but also as an analytic in cultural theory, philosophy, ecocriticism and the social sciences. How can art or philosophy provide new angles for making sense of and learning to live in the entangled and ‘Weird’ ecologies that we find ourselves in?

What is ‘the Weird’?

‘The Weird’ is distinguished from adjacent genres of fantasy, horror and science fiction by an uncanny aesthetic, a sensation of cosmic disorientation and imminence that passes from the subject to the reader, and that hinges upon two or more different worlds – in an ontological sense – becoming entangled or superimposed. In the so-called ‘weird tale’, the ‘monsters’ and ‘aliens’ are not from another planet: they are invaders from another reality system, experienced through noticings and encounters that unsettle ordinary perceptions of time, space, ecology, causality, or agency.[2]

H.P. Lovecraft is almost universally credited with the formalization of the Weird as a genre, and his style of ‘cosmic horror’ has had a vast influence on art, literature and philosophy. But Lovecraft did not invent the Weird, either in literature or in the popular consciousness. Long before his Elder Gods and eldritch horrors, writers such as Mary Shelley, Edgar Allan Poe, H. G. Wells and Ambrose Bierce worked with aesthetic, atmospheric and philosophical elements that would come to define the coordinates of the Weird.

Nor is the Weird limited to modern fiction or English language writers. Fairy stories, folktales and myths collected from oral and written traditions from around the world explore the weird and uncanny realms existing in or alongside ours; caves, forests, waters and misty twilights are borderlands and everyday portals of the Weird. The Weird has always been with us.

The Weird is often expressed in imaginative ecologies that challenge binaries and biological essentialism, and which play on (and with) scientific taxonomies and commonsense ‘differences’ or boundaries between biological taxa, states of matter, human and ‘other’ (see Fisher, 2016). This is exemplified in works like Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach Trilogy and Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy, just to name a few.

Resonant with Donna Haraway’s idea of the ‘tentacular’, the ecological Weird reflects a way of thinking and telling stories that de-centers the subject and unsettles the ‘rational’, making ‘…human exceptionalism and bounded individualism… become unthinkable’ (Haraway 2016: 30). Because of this, encountering the Weird can be horrific, a source of fear and avoidance. But it can also be a source of re-enchantment, fascination or of giving-over and embracing the inevitability of transformation. As Jeff and Ann VanderMeer contend, with the ‘abolition of the rational, can also come the strangely beautiful’.[3]

What can embracing notions like the Weird offer political ecologists and others trying to make sense of the current juncture? Can a weirdly re-enchanted yet sharply critical realism help us see new ways of exploring plural natures and plural futures, whilst compelling us to think deeply about the struggles that shape the places that we inhabit and the histories, forces, and scales that they enmesh? Can it help us to face the strangeness and alienation in contemporary society, opening up not only an expanded sense of earthly kinship and relationality, but also an expanded sense of possibilities that the material cosmos might contain?

References

[1] Tabas, B. (2015). Dark places: Ecology, place, and the metaphysics of horror fiction. Miranda. Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone world (11). Emphasis added.

[2] Fisher, M. (2016). The weird and the eerie. London: Repeater Books.

[3] VanderMeer, A., & VanderMeer, J. (2012). The weird: A compendium of strange and dark stories: Macmillan

Comic: Weird Ecologies

Download Tim Zocco’s original comic exploring Weird Ecologies, fantastical worlds and tentacular thinking.

Related resources

Enchanting Nature: Tentacular storytelling in the Great African Kelp Forest

Enchanting Nature: Tentacular storytelling in the Great African Kelp Forest

Roundtable with the Sea Change Project, makers of the film My Octopus Teacher, on their encounters with (and in) nature, and how they tell stories about their experiences and insights.

Contested Natures

Collection of sessions at the POLLEN2020 conference co-organised by the STEPS Centre in September 2020, including on kinship among different species, multispecies flourishing in urban spaces, and more. Create a free profile to browse video from the whole conference.

Natures: our theme for 2020

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

How is talk of crisis shaping nature and people’s views of it? How can colonial forms of knowledge, technology and power be challenged, and what might it mean to ‘decolonize’ the study of environmental change? What do alternatives look like, and how can we explore, nurture, imagine and live the relationships we might want for the future?

Enchanting Nature: Tentacular storytelling in the Great African Kelp Forest

Enchanting Nature: Tentacular storytelling in the Great African Kelp Forest