This is the last in a series of three blog posts by Andy Stirling about the theme of the STEPS Centre for 2019: Uncertainty.

In previous blogposts in this series, I argued that not all is as it seems in the politics of incertitude.

Deep intractabilities are papered over with the apparently precise language of ‘probabilities’. The everyday terminology of ‘uncertainty’ becomes dangerously misleading. And the apparently practical injunction to ‘keep it simple’ is revealed as pragmatic in a rather different way: as a means to maintain privilege by feigning control.

The question arises: what does all this mean for science? This will be the focus in this third and final post.

Science is about Opening Up, Not Closing Down

None of this is necessarily negative. It is simply how things are. Closure is not intrinsically bad – it is how things get done in everyday governance. So pressures unrealistically to close down incertitude are an inherent feature of the politics of knowledge.

Whether any given case is seen as positive or negative – justified or not – will depend in the end on the views in question and the values at stake. That’s not the problem. The problem is that pressures for closure remain so hidden and undiscussed.

It is here attention alights on the multiple roles of science. As recalled in the venerable Royal Society motto ‘nullius in verba’ (‘not on authority’), a distinctive aspiration in science lies (for all its flaws) in its recognition for the value of organised scepticism. Yet the political pressures discussed in these blogposts are increasingly leading science itself to be paraded as a body of doctrine. After several hundred years, history is turning full circle – science is moving from a process for challenging power-in-knowledge, to becoming an apparently rigid and uncompromising body of dogma in its own right.

For scientists, little is more motivating than the allure of incertitude. And for ordinary non-scientists, a large part of the fascination of science lies not only in the wonder of what has been achieved, but the mystery of what remains unknown. But in between these two forms of respect for incertitude among scientists and publics, there lie the crushing pressures of policy justification. The open-ended indeterminacies of science are alluring for people, but threateningly inconvenient for power.

The more this reality of incertitude is denied by rhetorics of ‘sound science’ and claims to definitively ‘risk-based’ objectivity, the greater the damage done to science itself. Although often presented as if defending science, denial of politics-inside-science, is actually deeply unscientific.

Indeed, key practices of science – like transparency, peer review, egalitarianism, communitarian sharing, experimental validation and healthy scepticism – all evolved expressly to address the ever-present ways in which power tries to shape knowledge. Science is not special because it avoids internal power dynamics, but because it at least tries to resist them. But it follows from this that science is rarely more undermined than when these aspirations turn into claims.

A number of growing trends threaten to compound this. For instance, why in debates like those around nuclear power or GM foods, is ‘trust’ typically spoken of only in one direction: for science by an acquiescent public, rather than by science for a questioning society? Why is it assumed that anything expressed in risk numbers somehow becomes magically objective? Underlying categories and relations are not mystically transformed by quantification. They remain as questionable as ever.

So we have an intense irony. To assert as ‘sound science’ the aggregation of single prescriptive policy recommendations under incertitude, is actually itself deeply anti- (as well as un-) scientific. Pressures for such assertions are less to do with science, and much more to do with the politics of justification. And it is when science is subverted by politics in these invisible ways, it risks its own deepest harm.

The Track Record of Closure

Nor is there any lack of evidence for the practical consequences of these pressures. Over many decades, it is a matter of record that scores of ecological and health threats have become recognised to be far more serious than official risk assessments initially conceded.

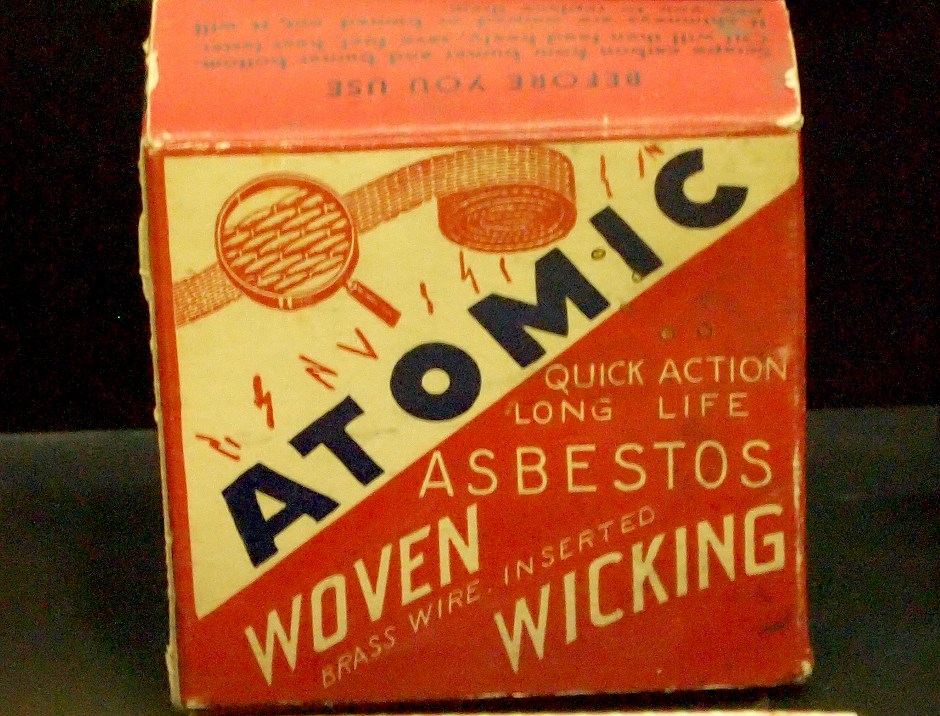

This is so, for instance, in histories of asbestos, heavy metals, many pesticides, carcinogens, ionising radiation, and endocrine disrupting chemicals, among many others. Each showed horrific limits to ‘risk-based regulation’. Yet risk-based rhetorics grow ever stronger, as if the fairy dust of probabilities, somehow erases all memory that these failures ever occurred in the past.

So – whether about safety, health or environment – official risk assessments of everyday products, pervasive chemicals and emerging technologies – continuously experience massive pressures to underplay incertitude. But perverse forces also work the other way. On the relatively rare occasions when the tables of science are turned, incumbent interests like tobacco or fossil fuel industries then find themselves on the other side of regulatory arguments – emphasising spurious uncertainties.

Either way, though (across different sectors), a recurring mantra slowly beats a defensive retreat. As new evidence emerges, the politics of incertitude typically remains oblivious for anyone who would look – dancing to its own ponderous music. One constant, however, is that it is those seeking to defend marginalised (rather than assert incumbent) interests, who bear the heaviest burdens. Defensive voices calling for ‘further research’, buy precious time for problematic practices to persist.

Indeed, there arises here a further sign of the hidden politics in incertitude as a world of its own. For assumptions that research will somehow always ‘reduce uncertainty’, involve the same kinds of simplistic and circumscribed linear thinking as probabilistic risk assessment. And the effects can be equally dangerous. In fact, as Einstein pointed out (and research itself often confirms): as the circle of knowledge widens, the circumference of experienced incertitude typically grows with it.

Incertitude and innovation

Again, these dynamics are not innocent. As innovations like new forms of agriculture or energy are built on the foundations of research, so these politics of incertitude intensify.

Sunk investments grow, institutional commitments harden, partisan communities of expertise proliferate to take ever greater ownership over what counts as ‘relevant’ science. In the process, stories about ‘risk’ and ‘uncertainty’ move ever further away from disinterested analysis and towards political polemics.

In areas like synthetic biology, human enhancement, autonomous systems, or artificial intelligence, controversies over ‘which way?’ to go (or whether to proceed at all), get artificially constricted into debates merely over ‘how fast?’ to proceed in whatever happens to be the direction most favoured by incumbents – and (as mediated by the incumbent’s own models) ‘what risk?’ to tolerate.

So in innovation debates, the expedient shaping of incertitude is just as striking as it is in discussions about risk. The picture is especially clear in retrospect. Also over many decades, alternative possibilities like renewable energy or ecological farming were long unduly side-lined in artificially constricted innovation discourse. With uncertainties obscured and these effects of power-in-knowledge concealed, incumbent interests doggedly resisted these alternatives as being simply ‘incredible’. Here again, power shaped knowledge to exclude inconvenient choices.

Only in settings relatively free from these pressures, did it prove possible for radical alternatives to escape these imprints of power in knowledge.

Take, for instance, wind power in Denmark through the 1970s and 80s. In larger countries – like the USA, UK, Germany, Japan and Sweden – the overbearing interests of the nuclear industry help snuff this option out. Only ‘under the radar’ in this distinctive non-nuclear setting of Denmark, was it possible to nurture design insights and intellectual property that have since led to one of the most important pathways towards a zero-carbon world.

The backlash against precaution

And it is here around innovation, that arguably the greatest pressures are arising – concerning the ‘precautionary principle’. Carefully negotiated in painstaking ways over many decades across multiple hard-fought, international legal regimes, various versions of this principles simply remind that ‘absence of evidence does not mean evidence of absence’.

Addressing all the issues discussed in these blogposts, precaution makes a point that is – to an unbiased eye – both eminently rational and straightforward common sense. No matter how strongly wished or convenient this may be, risk assessment does not fully capture all aspects of incertitude.

Yet a mounting backlash against precaution treats this basic principle of reason, as if it were inherently irrational. Precaution is increasingly dismissed as ‘un-’ (even ‘anti-‘) scientific. Ever more noisily, it is branded as a ‘dangerous’, ‘irrational’, ‘arbitrary and capricious’. The massive fallacy is propounded, that precautionary attention to uncertainty amounts to a quest for ‘zero risk’.

If it were not for all the noise – often sadly made in the name of ‘science’ – the mendacity of these accusations would actually be clear for what they are. To recognise the limits to quantification, is not to insist on a value of zero. To assert that this is so, is one of the most corrosive – but persistent – deceptions in this field. All precaution involves is an entirely rational understanding that single aggregated probabilities (of whatever value) are invalid under uncertainty, ambiguity and ignorance.

And in all the noisy clamour, a further falsehood is loudly and repeatedly asserted. In the fevered voices of challenged incumbencies, accusations are routinely made that precaution ‘stifles discovery’ and ‘limits innovation’. But in cases like asbestos, heavy metals, toxic solvents or ozone-depleting gases, it has been shown again and again that dangerous technologies are typically far more easily substituted than their protagonists initially insisted.

So precaution in such cases is not about banning any single path. To see it as such is to adopt the blinkers of associated entrenched interests, wishing to use risk assessment to side-line inconvenient criticism. What precaution is really about is helping to steer better paths for innovation in a complex world.

Reminding that basic realities trump imaginary expediencies, precaution is about honesty and rigour under incertitude.

There are plenty of powerful forces acting to steer technologies in directions favouring private interests. Across entire landscapes of innovation around health, agriculture, materials, mobility and information, the dominant incentives privately pressure for maximising shareholder profit, market share, intellectual property, product synergies and the accumulation of value in supply chains.

These forces can easily overwhelm the much weaker countervailing influences seeking to protect public health, minimise of environmental impacts or realise wider social benefits. In this context, precaution emerges as a relatively small way to help rebalance the far-from-level playing fields of innovation. And for vulnerable people and ecologies that have so often been betrayed by the narrow – often expediently manipulated – blinkers of risk assessment, precaution offers a crucial defence.

Enter the ‘innovation principle’

And this is where there now steps onto the policy stage an even more eccentric example of the concealed politics of incertitude. With precaution thus mischaracterised to be about blocking (rather than steering) innovation, many industrial lobbies are now covertly forcing upon bodies like the European Commission, a new attempt to reverse the gains made by precaution: the so-called ‘innovation principle’.

Arguably more than any other idea in this field, the ‘innovation principle’ parades the full range of fixations, fallacies and falsehoods discussed so far. This asserts that ‘innovation’ is what the most powerful voices say it is. It reduces all incertitude to risk. It treats technological change as a one-track race, rather than as an exploration of an open space of possibilities. It subverts democratic agency, as if choice were a matter purely for markets, experts and their sponsoring interests.

In all these ways, a so-called ‘real world’ of concentrated power denies the complexities of the ‘real real world’ outside. Rigid calculations subvert rationality. Partisan expertise undermines science. Locked-in infrastructures suppress wider innovations. Hubristic rhetorics drown out more humble reason.

Denying technological alternatives and social choices, the uncompromising language of ‘pro-innovation policy’ is under the straightjacket of ‘the innovation principle’) becoming ever more authoritarian. In any other area of policy it would be recognised to be irrational and cynical to brand critics of a specific favoured policy, as if they were generally ‘anti-policy’. It is little short of sinister, that such totalitarian language is somehow increasingly accepted around science and innovation.

Science as Democracy

So, caught between the rock of increasingly cynical policy languages and the hard place of ever-more entrenched global interests, emerging discourses around incertitude place science and democracy equally under threat.

And here there emerges a final dimension. For one way to understand growing authoritarian populism around the world is as a backlash to just this kind of globalising technocracy.

With science so overbearingly dragooned into the service of incumbent interests, expertise can hardly complain that it should be subject to criticism. These hidden politics of uncertainty-denial may be at the tipping point of some much wider and deeper tides. And with both science and democracy at stake, it is always the most vulnerable who stand to lose most.

Maybe less is more? Perhaps if policy expertise were less cavalier in its dismissal of incertitude, then the genuine – more modest – value of science would be better respected. But how can this be achieved? How can common cause be made between resistance to scientism and defence of science, in building a more open and convivial politics of incertitude?

The main point to note here, is that there is no shortage of available practical methods for nurturing this middle ground between what science illuminates and the incertitude in what this might mean for policy. With risk assessment and related techniques fixating so strongly on engineering closure, a host of other methods offer concrete ways to ‘open up’ a politics of incertitude that is at the same time more scientifically rigorous and more democratically robust.

Examples of these ‘Cinderella methods’ abound: sensitivity testing, interval analysis, scenario techniques, multicriteria mapping, interactive modelling, deliberative workshops, participatory appraisal, dissensus groups, civic research. Instead of pretence at single definitive solutions, these approaches systematically explore the conditions under which different reasonable answers emerge.

At their best, these approaches offer a compelling alternative to two equally negative pathologies. On the one hand, science and other kinds of social knowledge can (in a more humble mode) offer crucial insights and boundaries on what ‘policy based evidence’ would otherwise insist. Likewise, the greater transparency about how associated incertitude is shaped and framed under alternative perspectives, can mitigate the hubris of much current ‘evidence based policy’. The resulting more convivial balance might be thought of as ‘evidence bound politics’.

Either way, when undertaken together, struggles to ‘open up’ methods, institutions and discourses can be mutually reinforcing. Thereby less pressured by overbearing interests of incumbents, politics may become less polarised and irrational. Less subverted for the engineering of justification, science itself may recover some of its founding values of openness, communalism and organised scepticism.

Of course none of this opening up of methods, institutions or discourses offers a panacea to ‘solve’ challenges of uncertainty. Wider incertitude will remain defiant. Realities will still bite back in all the same old ways. But if humility and pluralism relax overbearing commitments, entrenched attitudes and polarised debates around science and innovation, then responses to incertitude may grow more diverse, flexible and adaptive.

It is thereby in respecting democracy as well as science that hopes lie for a more convivial politics of incertitude – enabling more robust and equitable outcomes of this perennially irreducible fact of life.

Uncertainties can make it hard to plan ahead. But recognising them can help to reveal new questions and choices. What kinds of uncertainty are there, why do they matter for sustainability, and what ideas, approaches and methods can help us to respond to them?

Uncertainties can make it hard to plan ahead. But recognising them can help to reveal new questions and choices. What kinds of uncertainty are there, why do they matter for sustainability, and what ideas, approaches and methods can help us to respond to them?

Find out more about our theme for 2019 on our Uncertainty theme page.