Two images stand out in David Attenborough’s new film A Life On Our Planet. The first is of the “blue marble”, the Earth, viewed from a spacecraft for the first time in the early 1950s. Seen from space, the Earth appears as a small disc, finite, lonely in the black void.

The second image comes back again and again throughout the film. A set of numbers, white against a dark screen. The date at the top: 1937, 1954, 1960, 1997; the human population, carbon in parts per million, wilderness, as numbers below. As the years pass, the numbers of population and carbon ratchet up, and the percentage of wilderness ratchets down. When we reach 2020, the numbers start to turn red: it’s an emergency.

These two images dramatise the way the film diagnoses environmental problems, reinforced by an intense visual language. Wildebeest roam over vast plains, filmed from a height. Elsewhere, multitudes of people fill the screen: performing acrobatic feats in a European street, pressed together at a festival in India, crossing a busy junction in Tokyo, a teeming crowd of football fans.

At the turning point, when the red numbers appear, we’re brought up to the present day. “We account for over one-third of the weight of mammals on earth,” says Attenborough. Shortly afterwards, he falters, overcome, filmed in close up. “I mean, we have completely… well, destroyed that world. Uh… The… Human beings have overrun the world.” A strong, unequivocal message about the need to control the global population follows immediately after.

Of course, threats to biodiversity, toxic pollution and the potential outcomes of climate change are very real and intensifying, and they require radical action now. These are problems which the film diagnoses in some detail. But let’s reflect for a minute: however sincerely expressed, this is an extraordinary way to talk about people’s myriad relationships with the natures around them. Humanity, first depicted as a series of crowds, then as a single species, and then as a weight. So what’s going on here, what kind of sense does it make of the problems that are faced, and what kind of action is implied?

The message is worth paying attention to. Attenborough has previously said, in an interview: “I have no doubt that the fundamental source of all our problems, particularly our environmental problems, is population growth. I can’t think of a single problem that wouldn’t be easier to solve if there were less people.” This matters: he is perhaps the best known public figure associated with environmental issues in the UK, and has recently begun to speak out on climate change and biodiversity policy at high-profile global events.

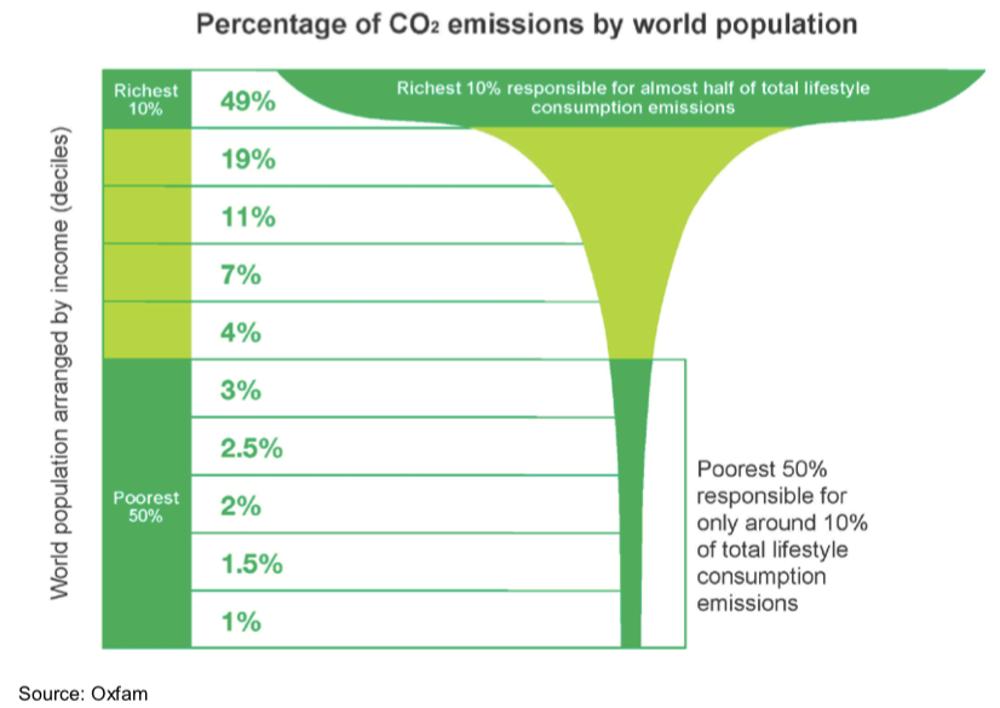

Ketan Joshi has gone into more detail about how the film’s rhetoric draws on a longer history of ideas about ‘overpopulation’ and population control – a history riddled with fear of exploding populations in the ‘Global South’ and an aversion to migration which persists until now. But this view is deeply flawed, when you look at how resources could be distributed differently, or who is actually responsible for consuming and polluting.

With this issue at its very heart, underlined in the most emotional and pivotal moments of the film, it’s inconceivable that its creators wouldn’t be aware of the history. But the message is strongly and simply expressed in both words and pictures: the expanding human population, consuming ever more land, is the key variable that drives the destruction of so much beauty and wonder. Humanity is flattened to “a single species”, a blot on the landscape, shrinking the wilderness that Attenborough loved, leaving behind the Eden of the Holocene.

The scenarios that follow, first fiery and apocalyptic, then the solutions – solarpunk visions of green sky-paths and forest-harvesting drones, promise a return to a more harmonious balance, powered by renewables and sustained by largely plant-based diets, with limits on fishing. We, the global ‘we’, face a choice between a scorched hell and a spacious paradise.

There’s a gaping hole at the centre of this analysis. Why has modern industrial capitalism taken the forms it has, extracting and wasting more and more intensely, and what alternatives have been suppressed? Why have certain forms of capitalism come to dominate, and how has this domination been promoted and maintained? Who are the ‘we’ who have extracted so much, and who are the winners and losers from all of this extraction? Could it have something to do with the unspoken drama behind the dates in the film – the 1930s, through the fifties, sixties and beyond – an Empire, officially dismantled and replaced by unequal relationships of trade and debt, violence, aid, sanctions, investment, international development, and now vast areas of land earmarked for green energy or carbon offsetting? What are the processes, relationships, ideas and forces that maintain the deep structures that enable this inequity and extraction, and how can they be broken apart?

Since the release of A Life On Our Planet, Attenborough has also mentioned capitalism by name, as a driving force of overconsumption. But in its language and framing, the film emphasises population numbers, not structures. In doing so, it glosses over the reasons why some have (and use) so much, when others are so sorely deprived.

What about the bit that follows afterwards: the seemingly binary choice between disaster and salvation? It reminds me of the science fiction series I’m currently binge-watching, Counterpart, in which the earth has been copied –around 30 years ago – producing two parallel Earths, side by side. In one, a flu pandemic has wiped out a tenth of the world’s population. Technologies, architecture, personalities, lives have all diverged. Imagine if there was a moment when you could choose between two futures. Popular environmental campaigning sometimes strives to create a feeling of such a pivotal moment. What if all of humanity, somehow, could come to the crossroads, and go the right way?

A new design concept for the #warmingstripes by @alxrdk showing how the stripes could evolve out to 2200, depending on emission choices pic.twitter.com/notGTQ8lS8

— Ed Hawkins (@ed_hawkins) March 20, 2019

I want to offer an alternative vision. We do not stand at the crossroads between two Earths. Rather, a multitude of different pathways is evolving in this world. Pathways from past to future branch and cross over, coexist and fight, wax and wane.

At every moment, in millions of places on Earth, an unimaginable diversity of futures is being made. Nobody, however rich or powerful, has their hands on the levers that will swing the planet from destruction to balance. No set of technical solutions, however clean and green they may be, will address injustice if it is not confronted as a scandal in its own right. Global development goals do not fail because of a simple lack of will. Cultures do not change by being controlled in a particular direction.

Yes, food and energy systems can become less wasteful or healthier through wiser investments and better techniques, but structures and cultures need to change too. And in a million different places, alternatives are being imagined and practised, not steered from above but emerging from below, often through painful conflict and resistance.

What vision of humanity will help to identify and support them? To put it another way: how can we truly understand the kaleidoscope of human diversity, the migrations of people from place to place, the struggles and disagreements, the staggering injustices that prevail, the solidarities, the ways people have responded to change and uncertainty, the possibilities as yet unseen…. if we consider humanity as a sheer weight? What values, ideas, imaginations, realities, histories, knowledges are lost?

In Attenborough’s earlier films, he shows at close quarters the miraculous variety of creatures that inhabit the planet. In the archive footage, he’s there in the jungle, up close with gorillas, or spying on penguins at close range, encountering a sloth face to face. This is the stuff that has made many people, including me, fall in love with an idea – however contrived – of nature. To move beyond the simple binary of consumption or protection, we need to get up close to people too, including to reflect on ourselves and where we stand.

Falling in love with humanity again in this way puts us at risk. We risk becoming sensitized again to the injustices produced when people and their fellow creatures are treated as simple objects. But it sets us free from the binary choice between apocalypse and utopia, of visions of a teeming mass of humanity on a blue disc, the Earth seen from above. There has to be a better way of seeing the world than this.

Our theme for 2020: Natures

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

Nature is all around us, but there are many ways of seeing different kinds of ‘natures’, and many efforts to involve it in forms of control or domination.

How is talk of crisis shaping nature and people’s views of it? How can colonial forms of knowledge, technology and power be challenged, and what might it mean to ‘decolonize’ the study of environmental change? What do alternatives look like, and how can we explore, nurture, imagine and live the relationships we might want for the future?

Find out more about our theme for 2020 on our Natures theme page.