by Glenn Davis Stone and Dominic Glover

“Golden Rice” is probably the world’s most hotly debated genetically modified organism (GMO). It was intended to be a beta carotene-enriched crop to reduce Vitamin A deficiency, a health problem in very poor areas. But it has never been offered to farmers for planting.

Why not? Because Golden Rice has an activist problem, according to its proponents. They insist that the rice would have prevented millions of child deaths by now had it not been blocked by anti-science activists.

In particular, they single out Greenpeace, which has campaigned against approval of Golden Rice as part of its broader opposition to GMOs. Greenpeace responds that its actions are not what has kept Golden Rice from reaching the market.

We study developing-world agriculture, including use of genetically modified crops, and are conducting ongoing research on Golden Rice, originally funded by the Templeton Foundation. We advocate keeping an open mind about Golden Rice, which may eventually have some nutritional potential in limited cases. But our view, based on numerous scientific studies, is that the rice is still beset by problems that have little to do with activists.

Filling a nutritional gap?

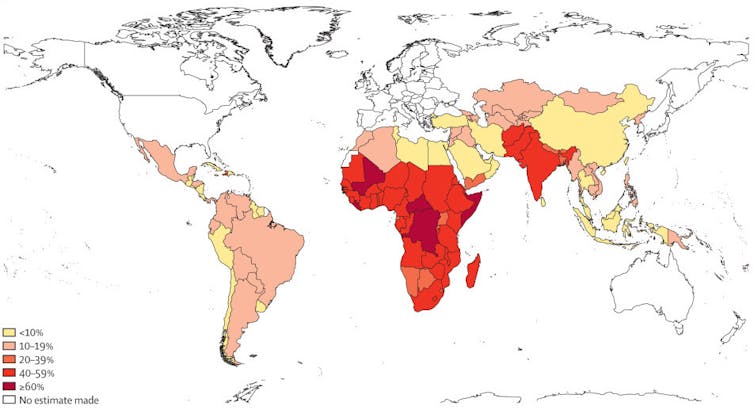

Vitamin A is one of many nutrients lacking in the diets of the world’s poorest children. Vitamin A deficiency, or VAD, can cause blindness and even premature death.

The vitamin comes directly from animal products and indirectly from beta carotene in plants, which the human body can convert to Vitamin A. Plant scientist Ingo Potrykus, who co-developed Golden Rice, has claimed that “VAD often occurs where rice is the major staple food.” White rice grains contain no beta carotene.

But it’s not rice’s job to provide vitamins. Most diets across Asia and Africa consist of a carbohydrate core such as rice or maize, which provides calories and bulk, and a sauce, stew or soup for flavor and nutrients.

Since rice is a poor source of vitamins and minerals, any child eating a rice-only diet will be sick. Genetically modifying rice to contain beta carotene is at best a band-aid for extreme cases of VAD, not a corrective for a widespread problem.

Decades of development

Potrykus and colleagues devised a strategy for producing Golden Rice in 1992, and announced in 2000 that they had developed an experimental prototype. Potrykus appeared on the cover of Time magazine with his rice, which the cover proclaimed “could save a million kids a year.”

The biologists were on to something, but the prototype was nowhere near ready for farmers or consumers. The beta carotene concentration was far too low, and researchers did not know if the plants would grow well. The prototype was also a rice variety that farmers in VAD areas would not grow.

In 2002 Golden Rice research moved to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in the Philippines to be developed for Filipino farmers. Meanwhile scientists at the global agricultural company Syngenta, which had acquired commercial rights to the rice, began to develop a new package of genes to improve the beta carotene levels. By 2005 they unveiled Golden Rice 2, which accomplished this.

Next, researchers inserted these GR2 genes into multiple plants, with the goal of introducing them without disrupting other genes. Each insertion is called an “event.” IRRI breeders took the most promising event and began breeding the trait into two trusty lowland rice varieties.

But there was a problem. Field trials showed that the introduced genes had indeed disrupted other genes and lowered the rice’s productivity, so breeders turned to a different event. By 2017 field trials showed that this rice grew adequately. The rice was submitted to the Philippine Bureau of Plant Industry, which designated it as safe in December 2019.

However, Golden Rice still has to be approved for commercial sale and still needs a company to grow marketable quantities of seed. Proponents’ claim that the rice would be given free to farmers is false: No one has offered to produce and distribute the rice seed for nothing. And even if someone were to grow marketable quantities of seed for sale, two crucial problems remain.

Unanswered questions

First, the claim that Golden Rice will remedy Vitamin A deficiency remains unproven. As IRRI scientists themselves stressed in 2013, “It has not yet been determined whether daily consumption of Golden Rice does improve the vitamin A status of people who are vitamin A deficient.”

Vitamin A is fat-soluble, and children with VAD rarely have fats in their diet. Moreover, they usually suffer from gut parasites and infections that make it harder to convert beta carotene to vitamin A.

A 2012 study, which has been cited over 70 times – despite being retracted in 2015 for breaching research ethics – seemed to show that Golden Rice would raise children’s vitamin A levels. But children in the study were fed balanced meals that included fats, thus demonstrating only that Golden Rice worked in children who did not need it.

Even the latest analysis of Golden Rice’s safety points out that research has yet to show that it will mitigate VAD. And by the time Golden Rice gets to undernourished children, its beta carotene level may be very low, since the compound deteriorates fairly quickly.

Second, there is no clear way for the rice to get to the children who need it. Projections of the benefits of Golden Rice assume that farmers will immediately grow it, but families poor enough to be affected by VAD often lack land to grow rice for themselves. VAD in the Philippines has been highest in Mountain Province, where farmers are unlikely to plant lowland rice varieties, and in part of metro Manila where no rice farming occurs.

To reach undernourished kids in areas like these, Golden Rice would have to be grown by commercial farmers and sold in markets. We examined whether farmers would plant Golden Rice in a new study of seed selection practices in a “rice bowl” area of the Philippines.

Farmers choose from a large and rapidly changing array of rice seeds, based on agronomic performance, market demands and local trends. Their choices show that varieties containing the “Golden” trait are out of fashion, overtaken by newer and better performing varieties.

Some might adopt Golden Rice if it could fetch a premium in the market, but extremely poor customers are unlikely to pay it. Farmers may need subsidies to plant Golden Rice, but it is unclear who would pay them to plant it.

An oversold solution

The old claim, repeated again in a recent book, that Golden Rice was “basically ready for use in 2002” is silly. As recently as 2017, IRRI made it clear that Golden Rice still had to be “successfully developed into rice varieties suitable for Asia, approved by national regulators, and shown to improve vitamin A status in community conditions.”

The Philippines has managed to cut its childhood VAD rate in half with conventional nutrition programs. If Golden Rice appears on the market in the Philippines by 2022, it will have taken over 30 years of development to create a product that may not affect vitamin levels in its target population, and that farmers may need to be paid to plant.

About the authors

Glenn Davis Stone, Professor of Anthropology and Environmental Studies, Washington University in St Louis and Dominic Glover, Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.