By Fateme Zare, Victoria Evia and Michael Kriechbaum

What skills and dispositions do researchers require for sustainability and transdisciplinary research? In this blog post, we want to provide insights on this question from the final session of the 2018 STEPS Summer School.

We attended this two-week course, together with 39 other early-career sustainability researchers from different countries and disciplinary backgrounds (such as environmental studies, innovation studies, biodiversity and tourism and sociology). After two weeks of committed academic and informal discussions, ‘walkshops’ and even dancing, we had to organize a session. Inspired by long discussions about positionality, identity and commitment that had emerged during the Summer School, we decided to address the topic of research skills, to explore what kind of skills researchers need when dealing with sustainability issues,

RESEARCHER SKILLS WORKSHOP

We organized this workshop session into different, interlinking activities. First, we asked our colleagues to identify their personal research skills and write them down on Post-it notes. No particular type of skill was defined. In other words, they could name whatever kind of skill they wanted (provided that they were perceived as helpful for their research). Following this, we asked our colleagues to attach these notes to their bodies and walk silently around the room, observing other people’s skills.

After some time of this silent observation, participants were asked to join with other people who had skills of interest that were thought or perceived to be complementary. The resulting (seven) groups were then invited to tag all their ‘individual’ skills on a diagram of a human silhouette, preferably on those parts of the body with which the skills corresponded most closely.

The groups discussed the collection and arrangement of their skills, then were given the option to add new skills that they thought were missing. These new skills included those which the group acquired collectively, but did not possess as individuals, or the sorts of skills identified as important for team-working, rather than individual work, and so only identifiable after group interaction. Finally, each group shared the main points with the other workshop participants.

THE FINDINGS

In the weeks after the Summer School, we decided to systematize and analyze some of the outcomes from the session, to address the following questions: What skills did these young sustainability researchers identify they have and need for their work? Where were these skills located on the body? What skills emerged as a result of people working together in groups?

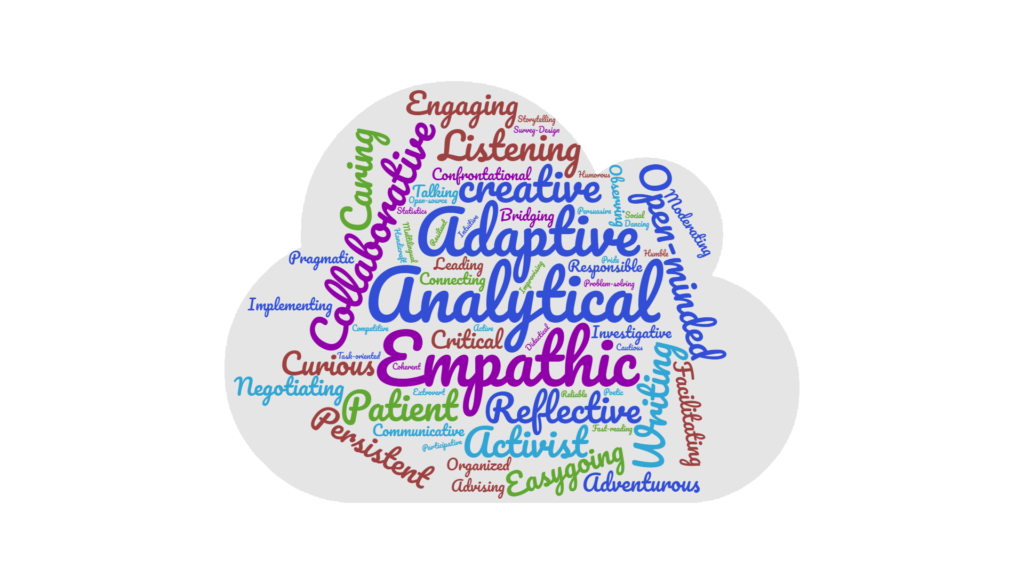

To answer these question, we, in a first step, digitized the emergent individual and group skills from the workshop. For simplification purposes, we summarized those skills that we thought were nearly identical, such as empathetic and compassionate, or analytical and precise. The word-cloud (below) depicts the frequency of these summarized skills (where bigger font means more frequent skills).

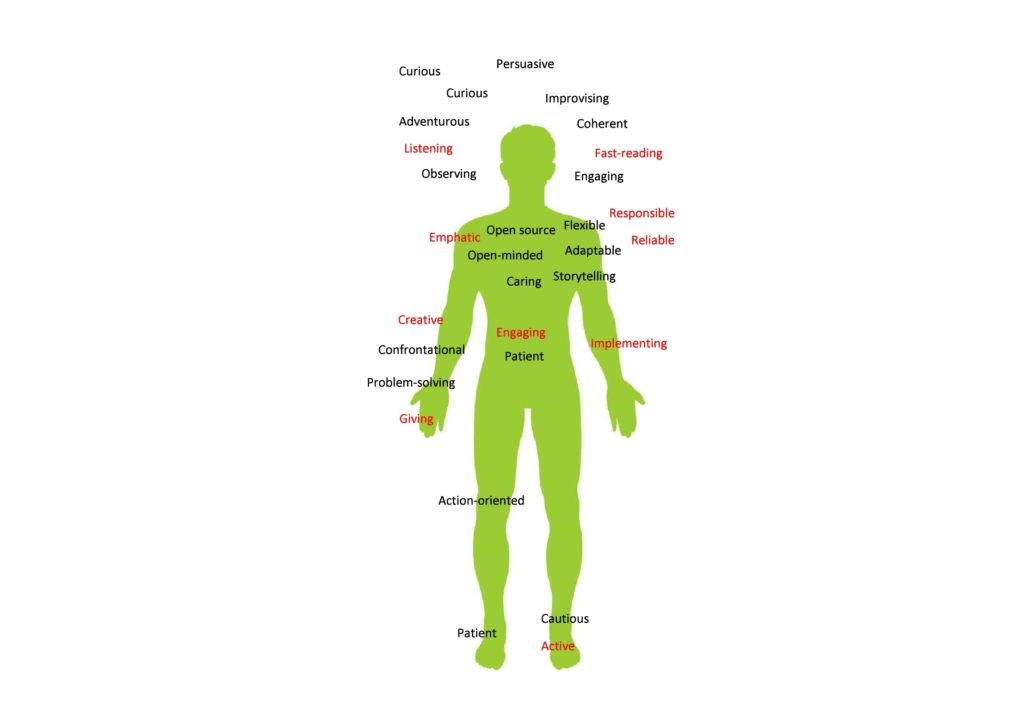

The next diagram (below) shows an example of a final ‘sustainability researcher’ silhouette from the workshop. Skills written in black correspond to the original Post-it notes (individual skills) and skills written in red the new skills that emerged after group discussion. In all the groups at the workshop, individual skills were located mainly in the head and chest or heart areas of the body. Most of the ‘group emergent’ skills were action and movement-related (active, collaborative, exploratory, giving, and implementing) and were located in limbs. Other skills related to feelings and attitudes towards others, such as being empathetic, engaging, reliable, responsible or sensitive, were located around the torso.

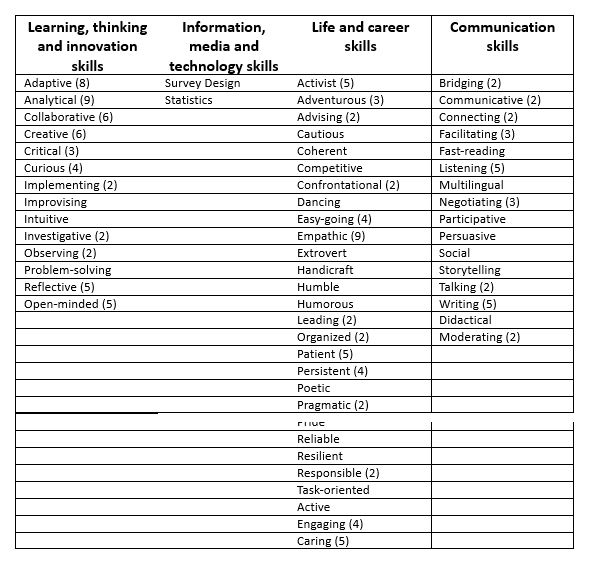

In a second step, we grouped the skills into categories. We established four categories based on the proposal from Anu Vehmaa and colleagues in their recent paper on the role of sustainable development in the education and early career of water and environmental engineers’. The categories they identify are:

- Learning, thinking and innovation skills

- Information, media and technology skills

- Life and career skills

- Communication skills

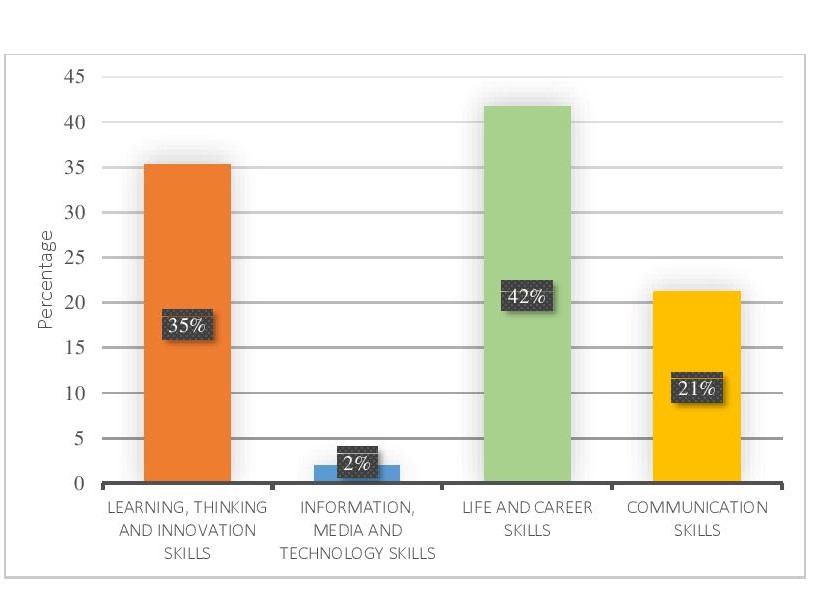

The graph (below) presents the distribution of skills from the workshop among these categories.

The graph illustrates that ‘Life and career skills’ were repeated the most, while ‘Information, media and technology skills’ were mentioned the least. Learning, thinking and innovation skills (such as being reflective) were also frequent in all groups. Communication could be thought of as being part of ‘Learning, thinking and innovation’, but because of its prominence, we gave it its own category. There is a difference between ‘hard’ skills (such as technical skills) and ‘soft’ skills (such as social and life skills), and, as Vehmaa and colleagues have argued, both are necessary for trans-and interdisciplinary research.

We found that, among the researchers at the STEPS Summer School, soft skills, such as life and career, learning and innovation, and communication skills were emphasized. Most surprisingly, many of the skills that were mentioned related to life skills, such as being empathetic, caring or patient. We also found a shared concern for individual hearts and minds being ‘overloaded‘ with skills, and the need to consider ‘action-related‘ and ‘creativity’ skills to complement their existing abilities as sustainability researchers.

A list of skills from all of the groups and their associated category is shown in the Table, below.

DOING, THINKING AND FEELING

As researchers with a focus on sustainability, we need to have a broad set of complementary skills that help us to work in trans- and interdisciplinary groups and deal with uncertain and wicked research topics. The outcomes from this Summer School workshop session indicate that the skills needed for sustainability research go beyond ‘hard’ skills, and relate to our capacities for creativity, learning and communication.

The identified skills also seem to be embodied and connected to affect, because we must be able to engage with other people and new situations and problems. Such flexibility and ‘openness’ could be important for confronting the challenges that come with working with different social actors and institutions on sustainability research.

Fateme Zare is a PhD Candidate at Australian National University.

Victoria Evia is a PhD Candidate CIESAS (México) and Teacher Assistant at Universidad de la República (Uruguay).

Michael Kriechbaum is a PhD Candidate, University of Graz.

The authors wish to thank all STEPS Summer School 2018 participants for the shared experience, especially Hanna Brouers who co-coordinated the skills session with us.

Applications for the steps summer school 2019 are open (until Sunday 27 January 2019). Find out more and apply.