I am very grateful to Laura Pereira, Victor Galaz and Johan Rockström for taking precious time to respond to the points I raise in my earlier blog. It is a huge privilege to benefit from such thoughtful and substantive reflections. This is all the more the case, since we agree that the issues at stake are so serious. So, I will take the chance here briefly to explore a few key implications just one iteration further.

Read the series:

- Time to rei(g)n back the Anthropocene? by Andy Stirling

- Reflections on “Time to Rei(g)n Back the Anthropocene” by Victor Galaz

- Seeing the Anthropocene as a responsibility: to act with care for each other and for our planet by Laura Pereira

- The Anthropocene, control and responsibility: a reply to Andy Stirling by Johan Rockström

- Anthropocene Definitions – Power, Responsibility, or Something else? by Manjana Milkoreit (Because it Matters blog)

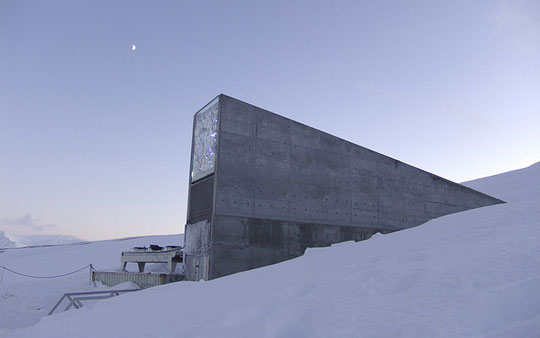

Svalbard Globale frøhvelv/Svalbard Global Seed Vault by Mari Tefre / Landbruks og matdepartementet on Flickr (cc-by-nd-2.0)

Most animating these respondents, is my argument that the Anthropocene conflates impacts with control – exercised ‘outwards’ over ‘planetary systems’ by a notionally homogeneous humanity. I contrast this with more diverse, overtly political, values and struggles of Sustainability – for instance emphasising care, responsibility, accountability and solidarities. What is crucial is that these latter non-controlling qualities are also oriented ‘inwards’ into human affairs, directly challenging incumbent interests and structures.

Some of this contrast is accepted – and I am very grateful for several points of support and reinforcement (which I will come to in a moment). But Victor directly contests the underlying critical picture of the Anthropocene as being about outward control. And, despite crucial areas of agreement, Johan views this only as a “perception”, which is “not primarily” true. Laura calls instead for a more positive way to ‘see the Anthropocene’.

Many Anthropocenes?

In my blog, I acknowledged that a variety of Anthropocenes can be found – and constructed. As with all ideas, this one can be inflected in many different ways. This is especially true where high-level policy dynamics lend tactical expediency to ambiguity.

Once a concept is elevated to what Victor rightly contextualises as an organising theme for large research funding programmes, then further strong incentives emerge for compliance. So I understand the pressures in the academic ‘Anthroposalon’ for terminological alignment, rather than potentially excluding criticism. With so much momentum and sunk investment, rei(g)ning back is hard to do! But – writ large – this is in the nature of the dilemma itself.

Crucially, my point is not about how the Anthropocene might be perceived under specific academic views, but what is generally distinctive about this as an incipient mainstream policy discourse, when taken as a whole. In particular, I am asking how it adds (or detracts from) hard-fought progressive values of Sustainable Development.

Over decades of struggle (and despite many imperfections) Sustainability represents an unprecedented crystallising of emancipatory movements into instruments of global governance. Rightly or wrongly, it is this precious political fulcrum for further struggle, that I see as being threatened and which I am seeking to defend.

So it is striking that, though contesting my own analysis on this point, none of the three respondents propose an alternative picture of what the Anthropocene distinctively adds to the progressive struggles of Sustainability.

Nor does any respondent refute any of the many prominent representative quotes and links I provide in order to substantiate that the theme of planetary control is indeed actually generally distinctive of mainstream Anthropocene discourse. I will not repeat this evidence here – it can readily be seen in my earlier blog. And it still stands. Simply to point out that the issues are complex, that individuals may hold differing views or that greater variety is possible, does not negate that it is this theme of control that remains dominant in the discourse as a whole.

Beyond ‘control’

This said, it is heartening that all three respondents are eloquent as to their own preferences for substituting control with other values that I argue to be far more distinctive of Sustainability. In itself, this seems very significant. It would be very positive if those working within the Anthropocene discourse were to emphasise this more.

And I greatly appreciate the agreement that Johan in particular expresses about the dangers of any notion of a “good Anthropocene”. This also seems a new and important development – and one on which it is crucial to explore the implications. I would be keen to work in support of this in any way I can.

So – beyond the word itself – it is essential to emphasise the strong practical common ground.

Why discourses matter

But words do matter. For all the scholarly creativities and parochialisms of the ‘Anthroposalon’, terms are not infinitely malleable. They are made sticky by institutions and cultures. And discourse helps in turn to reproduce and make durable, far more material structures and flows.

This is why it is important to acknowledge the underlying forces and meanings. Whatever particular academic communities might wish or believe, meanings are settled in much wider arenas. This is what makes it so important to attend to – and nurture despite its flaws – the hard-fought progressive legacy of Sustainability.

So, this is not as Johan suggests, a matter of “pinning” power relations onto discourses. The intrinsically ‘sticky’ cultural and material attachments of discourse, mean that no idea in its context, can really be (as Johan says) “neutral in power terms”. Whether we ‘pin’ them or not, power relations are ubiquitous.

This is not of itself bad. Power is not necessarily negative. But it is most insidious for progressive causes, when power is ignored (so becoming unaccountable). If the power dynamics of this discourse really were simply denied, this would be an especially grave reinforcement of the regressive implications of the Anthropocene.

What is being governed?

And this leads to a particular challenge from Victor. He wonders whether it is the ‘earth systems governance’ community’s strong emphasis on international institutions that creates space for what he holds to be my “misinterpretation” about control.

But – whether they be hierarchical or flat, global or local – the primary evidence for outward control lies not in the nature of particular ‘governance’ or ‘management’ mechanisms. Important as these are, they will anyhow be determined by incumbent forces and counter-struggles, rather than the imaginations of academics.

The clue for what really diagnoses this outward control is (as argued in my blog), given in the very name of these governance literatures: “planetary management” and “earth systems governance”. It becomes even more clear in the practice. With the focus on managing ‘Earth systems’ and ‘the planet’ itself, the issue is more the envisioned object of governance, than the modalities.

The distinctively explicitly-identified targets of Anthropocene governance thus lie not directly in entrenched industrial interests, technological infrastructures or cultures of inequality and consumption, but the natural processes of ‘planetary control variables’ and ‘Earth systems’.

The ‘outward’ orientation is very clear – helping to further distinguish Anthropocene planetary control from the more inward focus of Sustainability agendas – addressing the particular cultural, economic and technological causes of impacts rather than notionally intrinsic attributes of ‘humanity’ in general.

Of course, Victor is absolutely right to query what might actually be meant by ‘control’ in these kinds of discussion. Here, I spend a quite a bit of space in the blog exploring by reference to the history of science, how the realities of control are often far removed from the romanticised visions. What incumbent power likes to present as control, is often better understood as being about reproducing privilege. So it is actually this very ambiguity about control that I am concerned about.

In focusing as distinctively as it does on the general theme of control (rather than responsibility, care, solidarity, accountability, self-discipline or justice), the problem is as much about what the mainstream Anthropocene agenda threatens to obscure, as what it might actually do.

The Anthropocene and Geoengineering

On this, a further key point at issue is the linkage I make between ‘the Anthropocene’ as a diagnosis, and climate (and potentially wider) geoengineering as a prescription. Both Johan and Victor emphatically challenge this. But in the absence of any concrete arguments to the contrary, it is difficult to see why.

Here again, the contrast with the more ‘inward’ focus of Sustainability comes to the fore. Albeit unintended (even expressly disavowed), planetary managerial interventions like geoengineering are intrinsic to the distinctive ‘outward’ orientation of the Anthropocene. And when Johan talks of “managing the stability of the Earth” or “maintaining optimal Holocene conditions”, we surely have to ask – as my blog does – what is to become of the natural dynamism of the Earth?

Not only is the emphasis here again on outward control of planetary systems, rather than inward curbing of particular cultural, economic and technological impacts. But what seems neglected are the many forms of inherent, sometimes radical, natural forms of planetary dynamism. If (as seems clear) aspirations to equilibrium also address these intrinsic dynamics of the Earth itself, then the implication of geoengineering could hardly be more clear – and is all the more troublesome for being so obscured.

So, for all the alluring embroidery and veils – and whether or not intended and despite doubtless genuine commitments to the contrary – I believe that the main distinctive thrust of Anthropocene thinking must still be acknowledged to take the basic form I identify. Conflating impacts with control, it is about a supposed new geological epoch, defined by a homogenised humanity, invoking confident expertise, to intervene in planetary systems, so as to secure orderly planetary equilibrium.

Despite my respect for the expressions of disagreement in this exchange, I do not think any of these basic distinguishing characteristics of mainstream Anthropocene discourse have been refuted.

The Anthropocene and the SDGs

So, even where it is inadvertent, well-meaning or regretful, I remain very concerned that Anthropocene discourse threatens a serious regressive subversion of Sustainability. This is all the more insidious for being unintended.

As embodied in the hard-fought Sustainable Development Goals and their wider ‘sticky’ institutional movements and cultures, Sustainability is (for all its flaws) a precious progressive political fulcrum. It is about struggle not stewardship, care not control, responsibility not authority, solidarity not power – emancipating together all the unruly, unknowable diversities of the Earth and its peoples.

It is these crucial political responsibilities ‘inward’ into diverse human political structures and interests that are in so many ways, the opposite of the distinctive ‘outward’ Anthropocene vision.

Finding common ground

But perhaps most striking, is how this exchange has illuminated so many points of agreement. There is much common ground in the importance of responsibility and care rather than control, of social as well as environmental justice – and on the very serious perils of geo-engineering, eco-modernism and (for Johan and I at least) ‘the good Anthropocene’.

And Johan and I also seem to agree, that if the concept of ‘the Anthropocene’ is to be propounded at all, then it should be seen not as an inevitably-unfolding epoch of governance for planetary control and equilibrium, but as a disastrous transient episode of massively-rising impacts and injustices that it is essential to curtail.

In other words, if current exponentially accelerating impacts by particular human societies are to be viewed in presumptuous geological terms as if by the Earth itself, it is crucial to the Anthropocene analysis itself, that they would (uncurbed) not be a sustained era, but the ephemeral geological moment of a stratigraphic ‘horizon’. So, if a progressive view is to be taken, the term seems doubly flawed. The outwardly aggrandising ‘-çene’ suffix is as mistaken as the inwardly homogenising ‘Anthropo-’ prefix.

It is only under the spurious hubris of (if only tacit) ecomodernist transhumanism, that any ‘Anthropocene’ (‘good’ or otherwise) can become an extended geological epoch.

But all this said, the main point is for me to thank all SRC colleagues at the conference and in this exchange, for this opportunity to learn. Despite these vigorous exchanges, what all sides in such debates (including me) must acknowledge is that much remains intractably uncertain.

Here, it is action that drives understanding! And this is where the common ground is strongest: in radically progressive political transformations for protecting the Earth and its most excluded and vulnerable peoples. So, I look forward to continuing working alongside Laura, Victor, Johan – and so many others – in what promise to be some tough, diverse (but basically shared) political struggles!