by Ranit Chatterjee, Rohit Jha, Sahjeevan, Shilpi Srivastava, Lyla Mehta, Nobuhito Ohte, Shibaji Bose, TAPESTRY project

Kachchh is a dryland in Western India with a dynamic ecosystem. The livestock-based economy has always been one of the most important sources of livelihood for people there. In this arid to semi-arid region, pastoralism has been practiced for generations, providing an important source of food and income. However, in mainstream conservation and policy discourses, pastoralism is denigrated as backward and unproductive, and often blamed for the degradation of mangroves and their habitats.

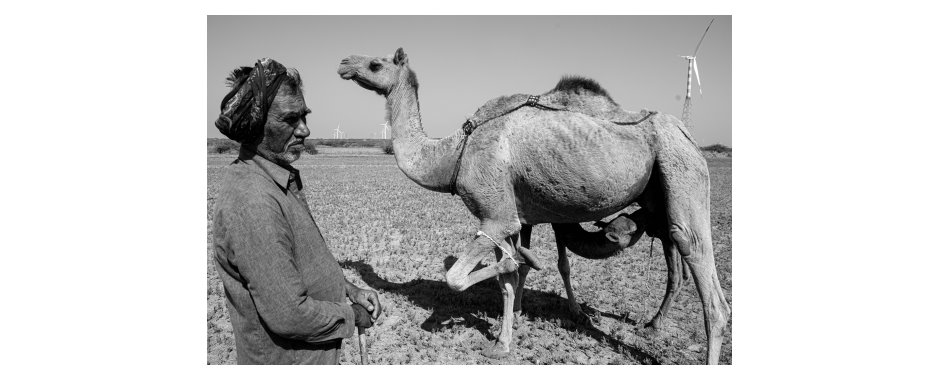

Livestock keepers in Kachchh are called Maldhari, which comes from the joining of two words: maal (animal stock) and dhari (owner/keeper). The Unt Maldharis (unt = camel) rely on camels for their life and livelihoods.

But times are changing. Traditionally, an extended family would have 400–600 camels. With time, that number has reduced to less than 100.

Young people are moving away from their traditional pastoral livelihood. But the rising demand for camel milk could bring a new economic boost for this traditional way of life.

Camels are well suited to Kachchh’s semi-arid landscape.

The Kharai (salty) camels of Kachcch — unique in the world for their ability to swim — are mostly restricted to the coastal belt of Kachchh. They graze on the mangroves that grow along the coastline and in the bets (islands). The pastoralists believe that this grazing stimulates the growth of the mangroves, helping to maintain a balanced ecosystem.

In addition to climatic uncertainties — droughts and, more recently, floods — the aggressive pace of industrialization has substantially altered the landscape. Industrialisation has resulted in the loss of common grazing lands, denudation of mangrove forest, water and land grabs. This has also threatened the survival of Kharai camels, who mainly rely on mangroves for their survival.

The Kharai camels are strong swimmers, with unique webbed hooves adapted to their environment. They follow specific routes between the coast and nearby islands, sometimes staying on the islands for 3 -4 days at stretch. In times of floods, the camels are also used to help rescue stranded people.

The Fakirani Jats, who are known for their camel breeding skills, link their culture, health and wellbeing with the Kharai. A commonly-heard phrase is: “What is a Jat without the camel?”

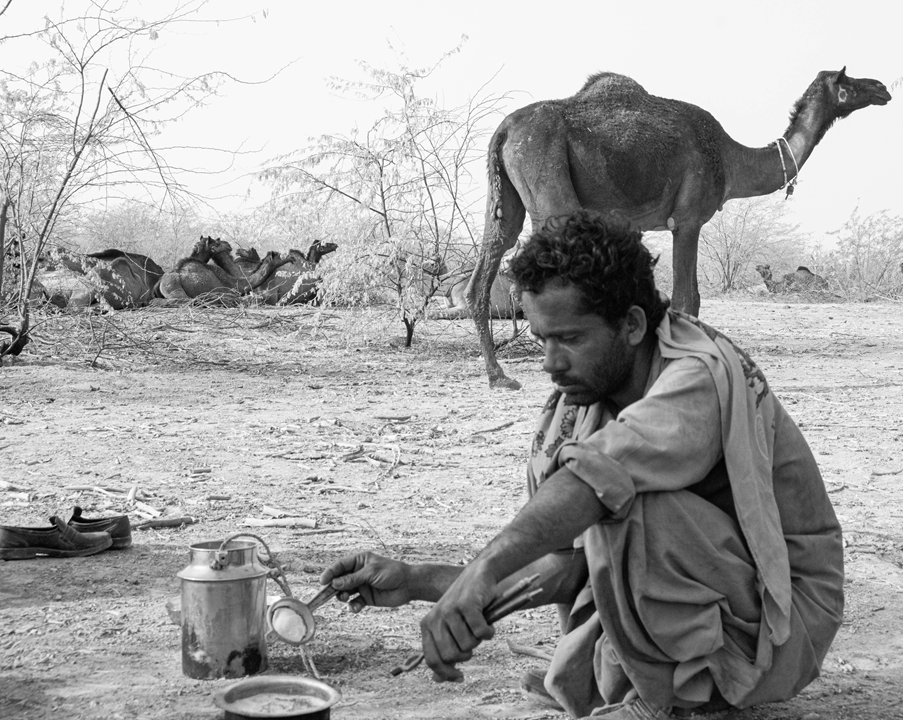

The pastoralists are aware of the medicinal value of camel milk. They believe that camel milk can cure or treat many diseases. In the past, a pastoralist would only survive on camel milk for days at a stretch — though more recently, dietary habits have changed.

There is a Kutchi saying: “Milk, like sons, can never be sold”. The female camels are also considered sacred and could not be sold. However, with the changes in dairy as well as in the wider landscape, milk is being sold now.

Camel milk has been found to have many advantages over cow milk. It has high nutrient value, and can be consumed by people who are lactose intolerant. Some studies have recommended it as an effective treatment for diabetes.

It is a common practise to let the baby have the first share of the camel milk. The rest is consumed within the household, and the surplus is sold.

The use of camels has also changed over the years. The age-old traditions of using camels for tilling agricultural land, using their dung as manure, and selling male camels, have declined. Meanwhile, household costs and the expenses of maintaining camels have increased.

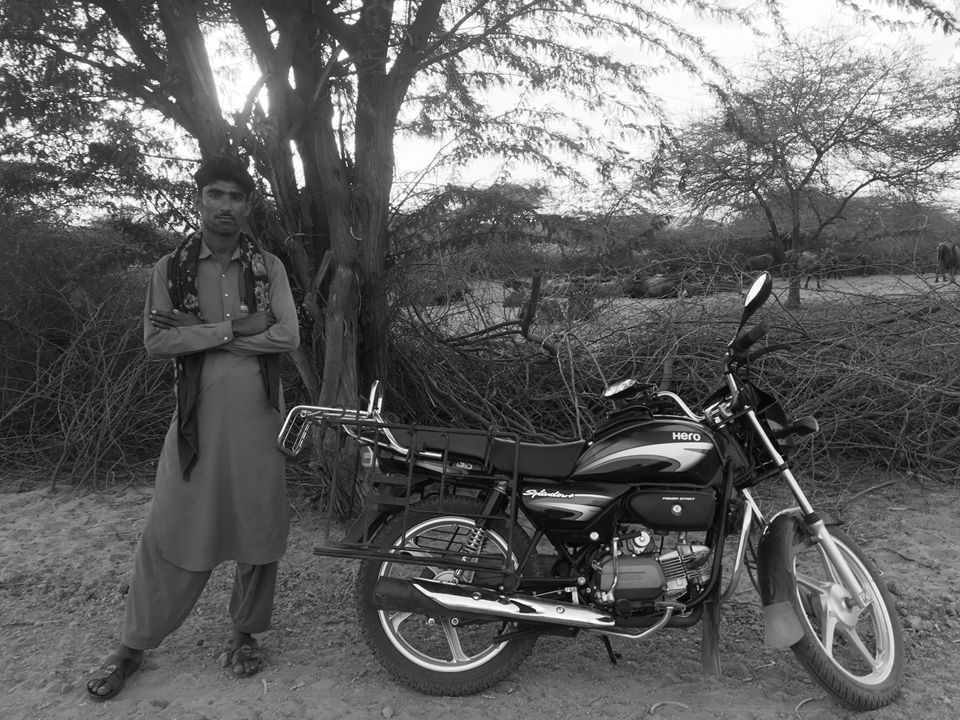

This has led some pastoral households to diversify their income. Young people are moving away from their traditional livelihood.

The older generation of pastoralists in Kachchh see this as a serious challenge to the conservation of the Kharai camels, and the continuation of their culture. But the rise of the camel milk business may yet bring hope for people’s livelihoods, and for the future of the camels of Kachchh.

The camel milk initiative is a key example of grassroots mobilisation, alliance-building with private (Advik Foods) and cooperative dairy chains (Sarhad/Amul), Sahjeevan and KUUMS.

But there are certain challenges. Camel milk has a low shelf life because of its high salt content and can turn bad quite quickly unless properly refrigerated. Another challenge is the saline taste of the milk which is proving to be a deterrent in increasing consumer demand. Companies like Amul are experimenting with flavoured camel milk to increase the acceptance.

Our research is taking place at a crucial juncture when camel rearing is said to be witnessing a revival. Due to the efforts of the NGO Sahjeevan, and the Kutch camel herders’ association (KUUMS), the Kharai camel was recognised as a distinct breed (2015) by the government of India.

To preserve this distinct breed and sustain the network of milk collection, traditional grazing routes must be restored; and the existing natural resource base must be protected (i.e. water and fodder resources, including mangroves habitats, on which the Kharai breed depends), thus bringing wider benefits to the pastoral community.

Photo credit

All photos: Ranit Chatterjee

About the research

The TAPESTRY project is working in three different ‘patches’ across India and Bangladesh, creating opportunities for interactions with people in marginalised environments to co-produce transformative change. These people are on the front line of climate change and other uncertainties, including those from industrial development, pollution, urbanisation, and other forms of economic and social change.

The research on the camels of Kachchh is part of this project. Other research explores the traditional fishing communities and mangroves in Mumbai; and local people’s innovations in food production, and their responses to climate uncertainties, in the Sundarbans delta.

Visit the TAPESTRY project website to find out more.