This year’s African Green Revolution Forum (AGRF) took place online, hosted out of Kigali, Rwanda. Chaired by the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), the AGRF is a high-profile global summit that brings together international donor agencies, governments, African leaders and agribusinesses. The summit is an annual opportunity for them to plan, mobilise and coordinate investments, policies and business cases to promote the continent’s agricultural intensification agenda.

Findings from our research in Rwanda shed light on whether this agenda is working for the country’s smallholder farmers. In this blog post, I reflect on what our findings mean for Rwanda’s policy and the wider project of an African Green Revolution. I also suggest how the processes that aim to transform agriculture in Rwanda and beyond could be made more inclusive.

What is AGRA doing?

AGRA’s raison d’être – unleashing an African Green Revolution of its own right – seeks to catalyse a pan-African agricultural transformation through technological innovation and productivity-led intensification.

In a nutshell, the strategy aims to change farming in Africa from subsistence-based production to high-value commercial enterprise. The key ingredients are the more intensive use of chemical fertiliser and hybrid seeds, and the commercial integration of small-scale farmers into the market ‘value chain’.

The aim of ending hunger and alleviating poverty through technological solutions is nothing new. But the continental scale of investment (around $1bn in funding since 2006), and the all-encompassing scope of roles that AGRA plays – high-level convenor, policy advocate, technological adviser, private sector partner, and crucially, grant maker and implementation supporter – make AGRA one of the most influential players in African agriculture today.

AGRA: A proven solution for Africa?

The agriculture development experience of Rwanda, a prominent AGRA member country, is a notable example. The government’s vision of the future of agriculture and its policies are closely aligned with AGRA’s approach and the ethos of the Green Revolution. So much so, in fact, that the former minister of agriculture in Rwanda, Dr Agnes Kalibata, at the end of her term, took the helm of AGRA to replicate the Rwandan model and to champion it to the rest of the continent.

However, the jury is still out on whether AGRA has achieved its goal of increasing incomes and improving food security for 30 million farming households by 2021. AGRA claims to have gone through “an internal integration process to work from the point of view of smallholder farmers [which led to] fundamental structural and cultural changes” in its approach to agricultural development. This process was meant to enable AGRA to integrate together proven solutions “into a single package that changes the lives of farmers and ultimately, the futures of entire countries […]” (AGRA’s integrated approach).

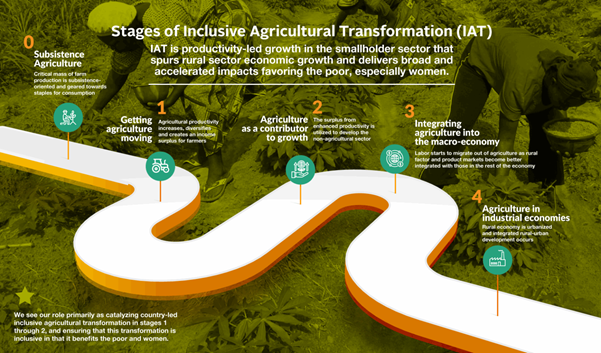

However, while inclusiveness is central to AGRA’s agricultural transformation narrative and forms the basis for their programme’s theory of change (see diagram), critics have questioned how inclusive AGRA really is. They have pointed out that such a productivity-led growth approach remains misleading, narrow and inaccessible to the majority of smallholder farmers in sub-Saharan Africa.

In the absence of independent and peer-reviewed impact assessments, a recent report from Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung and a working paper by Wise (2020) raised substantial concerns about the organisation. They criticised its dismissive attitude towards farmers’ agency and lack of inclusion, as well as a lack of significant evidence of impact on the lives of millions of farmers where AGRA operates.

Our own research in Rwanda asks whether smallholders farmers benefit from the current approach to agricultural intensification. The findings suggest a mismatch between the government’s approach and policies, and the way that many smallholder farmers actually work and how they plan their livelihoods. A summary of the findings and their relevance to policy (PDF) is available.

The study was conducted in two (rural and peri-urban) communities in Rwanda. We asked whether and which kind of smallholder farmers managed to engage (or not) with the government’s agricultural intensification policies. We also highlight the potential ramifications that the government’s intensification plan poses to the different types of farming households.

The study’s mixed methods approach – involving and learning from over 200 farm households through quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews – offers a rich and in-depth analysis that can cast light on how farmers themselves view these policies and react to them, answering some of the unresolved questions surrounding ‘Green Revolution’ policies.

Understanding the variation and diversity in mixed farming

Typically, farmers in Rwanda take a ‘mixed farming’ approach, with a judicious mix of rearing livestock and growing crops. The practices involved in mixed farming are highly diversified and labour intensive. While they are often considered as inefficient and economically unviable, the diversity and variation within mixed farming and their commercial potential are inadequately researched.

The farming households we worked with on the study had varying capabilities and priorities for their livelihoods. These variations were reflected in the different strategies they used to integrate crops and livestock. For instance, a dairy cow with similar genetic traits and yield potential could be used very differently on one farm compared to another. These differences would depend on the production options and resources that are available to them, so how the dairy cow was used in ‘intensification’ strategies would look very different.

The study also revealed that, although smallholder farmers’ practices and livelihoods are dynamic and precarious, this is overlooked by the current policy approach. One example of this is the lack of research funding and commercial interest in investing in small ruminants such as goats. These animals are often relied on by economically vulnerable families, as they can thrive in low-resource environments. They play a dual role of productive-and-protective asset, offering an economic ‘safety net’ to these families.

The study also revealed that, although smallholder farmers’ practices and livelihoods are dynamic and precarious, this is overlooked by the current policy approach. One example of this is the lack of research funding and commercial interest in investing in small ruminants such as goats. These animals are often relied on by economically vulnerable families, as they can thrive in low-resource environments. They play a dual role of productive-and-protective asset, offering an economic ‘safety net’ to these families.

Our findings suggest some areas to direct investment in the future. This includes investing in research and development of alternative non-commercial inputs and production methods, such as organic farm animal manure and the use of crop residues as animal feed, among others. These are currently widely used by smallholders to minimise the risks of failed harvests, enhance their resilience and sustain soils and livestock health.

Implications for agriculture and food systems in Rwanda

As I write, the world is still unravelling and grappling with the devastating impact of COVID-19 on agriculture and food systems. It is high time to rethink a social and economic recovery plan that appreciates the challenges that smallholder farmers face. In doing so, we need to recognise the diversity and complexity of integrated production that millions of smallholder farmers in Rwanda continue to face in their intensification efforts.

Therefore, any policy promoting a rapid transformation of production methods needs to take account of the diversity of Rwanda’s smallholder farmers. It needs to recognise the various types of farming practices and livelihood aspirations that shape and influence households’ decisions to engage (or not) with the government’s intensification and development initiatives.

To ensure a more inclusive, resilient, and just agricultural transformation process to take root in Rwanda, AGRA and its strategic partners must understand the processes through which agricultural transformation unfolds for specific types of farming households, and devise appropriate and supportive development measures.

Six concrete recommendations are proposed to help smallholder farmers smoothly transition from subsistence to commercial-based farming, while taking into account their differing capacity to make investments and take on risk in adopting intensive production:

- Improve organic manure management both at the community and household level

- Continued support in subsidised inputs is needed for a foreseeable future

- Making the intensive one-cow production system more affordable

- Invest in genetic improvement of small ruminants and product diversification

- Protect the livestock assets through a district-wide identification system and community surveillance

- More research and new policy strategy is needed for the peri-urban and urban farming and food systems.

Read more

For a summary of the research findings, read the policy brief Enhancing crop-livestock integration for more inclusive development in Rwanda (PDF)

About the author

Sung Kyu Kim is a postdoctoral researcher at the Science Policy Research Unit. This blog post and the accompanying briefing draw on his ESRC-funded research Pathways of crop and livestock intensification for Green Revolution in Africa: Evidence from Rwanda.