By Beatriz Ruizpalacios, Lakshmi Charli-Joseph, Hallie Eakin, J. Mario Siqueiros-García, Rebecca Shelton, Pathways Network

The urban wetland in Xochimilco, Mexico City, and the traditional agricultural areas within it, are undergoing rapid change and degradation, driven in part by the lack of regulation of urban growth near and within the wetland ecosystem. Strategizing on the best way forward has been difficult for decision-makers, given the polarizing positions of two main stakeholders: the traditional farmers (chinamperos) and the residents of unregulated and often illegal housing developments.

(For more background, see our previous blogposts: How rethinking local people’s agency could help navigate xochimilco’s troubled waters and A day in the Chinampas.)

One of these positions appeals to basic needs, like maintaining traditional agricultural livelihoods and the ecosystem and its services; the other emphasizes securing a safe living space and access to water and sanitation. The arguments made by both constituencies are logical and deeply felt, but the lack of agreement ultimately puts in jeopardy the present and future of the land and ecosystem.

The task is to overcome such locked-in situations in order to navigate towards a more sustainable development pathway for the Xochimilco urban wetland. This requires challenging assumptions, dominant paradigms and even meanings and core values held by the diverse stakeholders. But discussing relevant and contrasting narratives has proven difficult – this has impeded each group from recognizing the reality of the other’s experience, and from exploring alternative solutions or pathways.

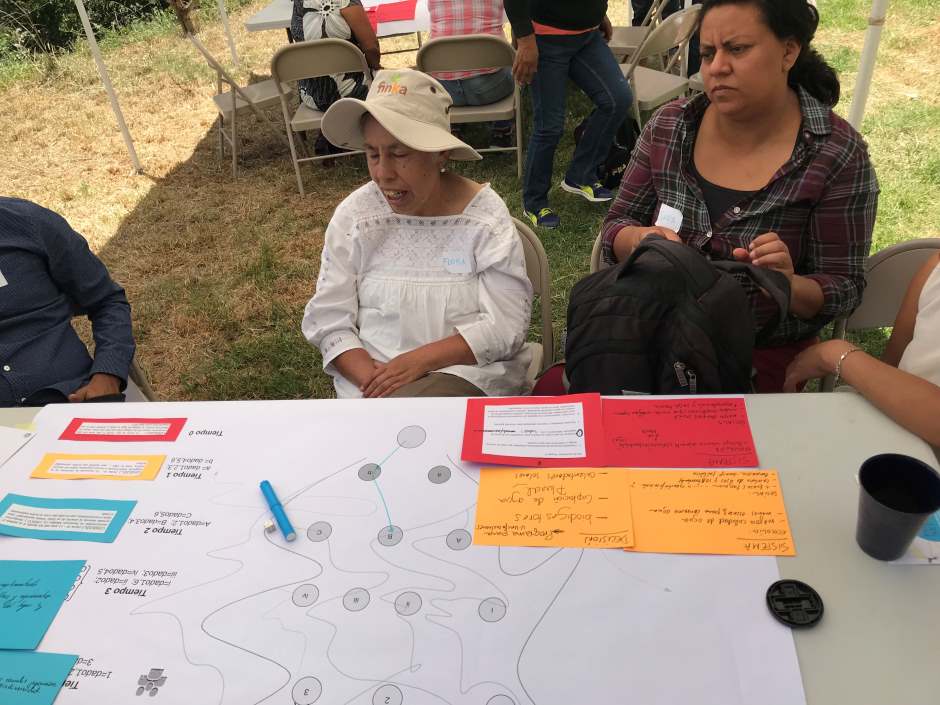

To address this challenge, we have been running a T-Lab (Transformation Lab) with a group of people in Xochimilco who have different perspectives and experiences of the challenges there. As part of our T-lab in the Pathways Network, the North America Hub designed a Pathways to Sustainability Game. The game aimed to offer a safe space for participants to explore decision-making in both favorable and adverse contexts, while recognizing and challenging each other’s positions.

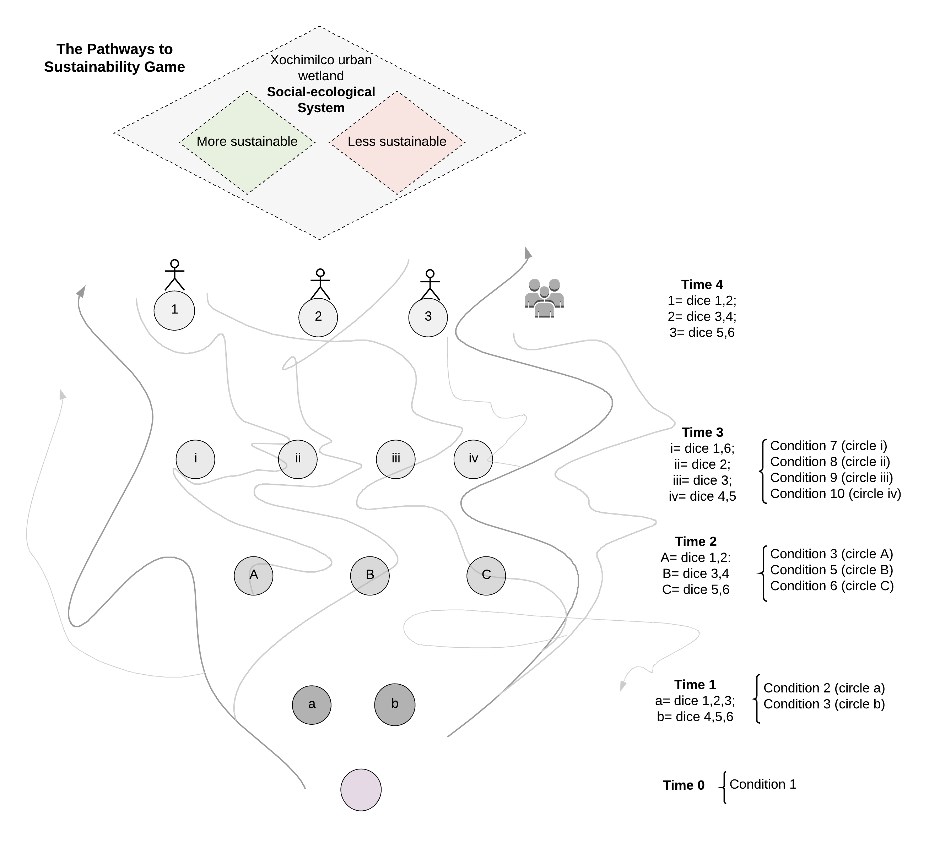

The game was designed for participants to grapple with the very concept of ‘pathways’ – the idea that movement towards sustainability is a process of constructing alternatives and making decisions, while reflecting on how the system looks, and hence learning from every action taken – and the role of uncertainty in navigating such pathways.

To explicitly address the tension between urban residents and wetland users, we invited six new participants to join in the game and play alongside our regular T-Lab participants. Five of them were residents of irregular settlements, both on the chinampas as well as in other conservation land on the hills, and one was a chinampa agri-producer (or chinampero) and conservation activist.

We set up three groups, each with the same number of informal settlement residents and chinamperos, and including representatives from both urban and wetland areas. Each group also had one or two participants from academia or an NGO to bring a different view to the group; as an outsider, as an advocate of either of the two opposing positions, or to offer a more systemic view. Each group had two facilitators from our T-Lab team.

How to play the game

The aim of the game for the participants was to steer the system towards a more sustainable pathway and choose specific actions and projects to reach it.

The starting point of the game was defined as a moment after the 19 September 2017 earthquake in Mexico City, a real-life event that had affected everyone that was present, and after which there have been several rebuilding initiatives. For the purpose of the game, each of the three groups formed a committee of neighbors in charge of the future management of the Xochimilco urban wetland area. Each committee had annual funding for three years to set a common goal and choose specific actions and projects to achieve it.

The game consists of sequential phases that reflect the three years of funding allocated to the committee. Each committee began the game at ‘Time 0’ and finished at ‘Time 4’. At the beginning of every year, each committee had to define an action for which it had unrestricted, but realistic, funding. At ‘Time 0’, we gave the committee a set of actions to choose from; for the subsequent phases, each action was created by the participants.

In addition to making its own decision, each year, by the throw of the dice, the committee faced specific ‘conditions’ that could either hamper or favor their chosen goal. The system created in the game subsequently would consist of five states: a starting state (Time 0); three states which each emerge from the outcome of the committee’s decision and the ‘condition’ they encountered by rolling the dice; and, finally, an ‘end’ state (Time 4).

Observations from the game

By encouraging participants to engage in a safe tacit-learning experience, we fostered teamwork in relation to a shared long-term goal, charging the participants with the responsibility for moving the whole community forward, even in situations that required big compromises by some or all team members.

We found that the game also stimulated rich conversations: these were sometimes triggered by conditions that reaffirmed participants’ opposing positions and which they found difficult. Other conversations were sparked by participants sharing their experience of navigating smoothly through decisions that in the ‘real world’ would have been controversial.

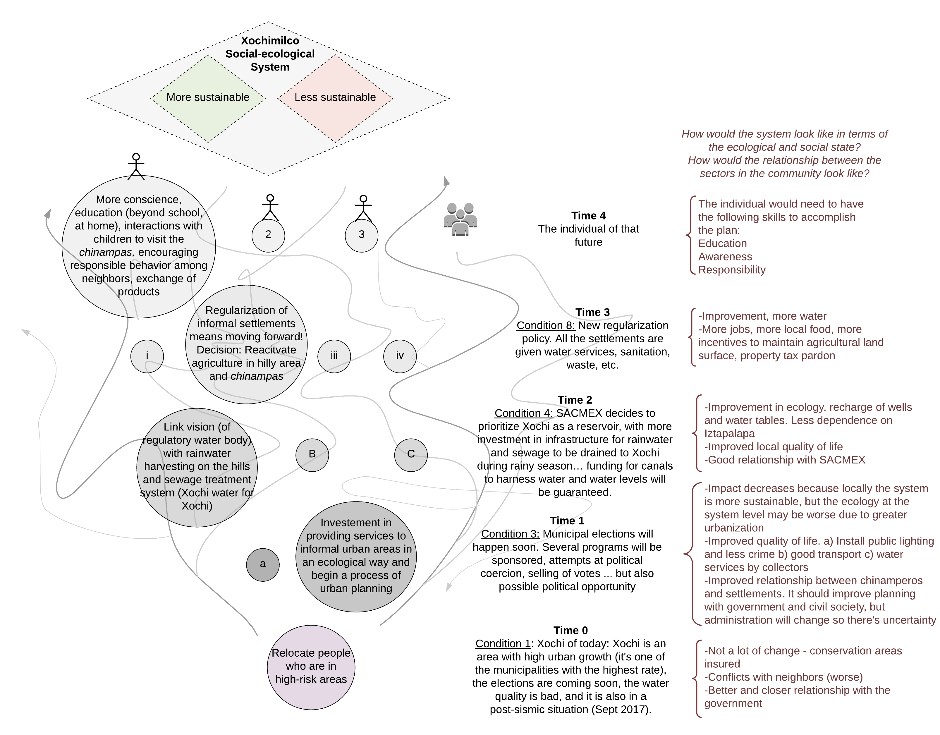

Because the game required the committee to reflect on the winners and losers (including environmental impacts, social relations, and political relations) after each action they implemented, they were able to explore each other’s framings of the problem, as well as consider possible implications of their choices for different attributes of the system.

During the game, one of the most striking narratives that emerged from the discussions of participants related to the damage caused on the land by irregular settlements, which most considered to be irreversible. Nevertheless, they also acknowledged that urbanization cannot be stopped, and accepted that these settlements would only become more numerous. They acknowledged that some people have been living in them for more than 30 years, right next to traditional agricultural chinampas.

The proximity of the settlements has fed the harsh, antagonistic relationships between the urban dwellers and chinamperos. However, having to work together in the game towards securing a shared goal, while facing political and social obstacles, steered the conversation towards important shared concerns.

Empathy and diversity

The participants agreed that promoting empathy among neighbors was a solid foundation on which to work, and that a means for achieving change was to build on small but cumulative results from which all the community could benefit.

However, they first had to acknowledge the diversity in the community, so several groups designed their interventions to first address one concern (e.g. urban services for irregular settlers) and then, in a subsequent action, to address the needs of the wetland ecosystem. One group proposed to implement an environmental education programme so they could help raise awareness of the system’s diversity and dynamics; they suggested that their preliminary results would serve as an example to gradually encourage everyone in the community to participate.

Risks and recovery

Another group discussed what risks are faced and by whom, and what ‘recovery’ means in an earthquake-prone environment. Relocating people from the cracked and sinking chinampas raised questions of corruption and the human rights violations that occurred when they first acquired their land.

In contrast, another group discussed introducing innovative constructions to allow families to keep their homes on chinampas and conservation land. They explored green infrastructure at the local level and considered its consequences at a systemic level, while trying to balance human wellbeing and environmental integrity at the same time.

The third group became very appreciative of the benefits of cooperation among themselves, even with their opposite positions in the system, and with other stakeholders, in particular the government and the rest of the community. They championed opening up each action they decided upon to be as inclusive in its goals as in its implementation.

Reflections on the process

While the participants acknowledged that the game was a “fantasy” and an idealistic way of envisioning change, they also found the experience constructive. They felt excited with the actions proposed and hoped to have a “magic wand so everything would work out quickly”, in the words of one participant; but they were also aware of the need for effective communication if they were to have ample support and participation from their community.

Simulating agency

In the brief one-and-a-half hours during which we played, all participants experienced the responsibility of making decisions and navigating different pathways that could steer the Xochimilco wetland system towards more sustainable states. In this sense, we simulated the role of collective agency in system change, under the pathways framework.

This game allowed the participants to explore how they could collectively make decisions in the midst of the uncertainty brought about by the dice, while navigating a pathway of their own design to a more sustainable Xochimilco. They explored the fact that by working as a team they could build a wider and stronger network to work with, and that this network would eventually become an important bridge to reach even the most indecisive or opposing members of the community. As one of the participants said: “It is not the same to endure the problem as it is to try solving it”.

We designed a game that would embody the theoretical principles of the Pathways approach in a way that people, through their experiences, would find easy to assimilate. As such, we propose that this game has the potential to transcend the scope of our own case, and appeal to other researchers and practitioners.

Find out more about the Pathways Network project, and read about the Xochimilco case study here.