This is one of a series of Stories of Change from the ESRC STEPS Centre.

From exposing land grabbing and carbon forestry, to debates about the Anthropocene and ecological crisis, STEPS work explored how people view and interact with the nature(s) around them.

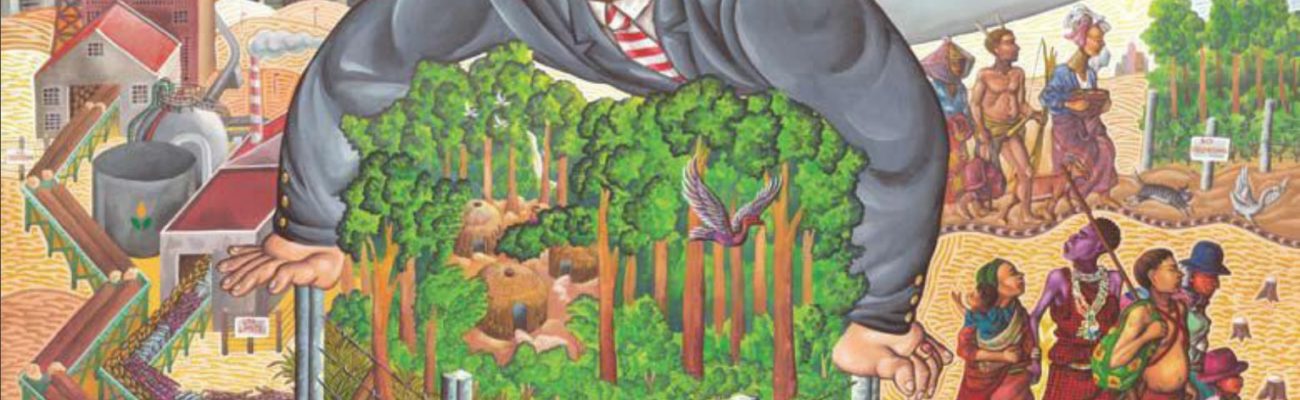

In 2007 and 2008, financial markets began a slide into the worst crisis since the Great Depression. As food prices rose, there was an explosion in large-scale land deals. Land across the Global South was being increasingly seen as a source of alternative energy (primarily from biofuels), food crops, mineral deposits (new and old) and reservoirs of environmental services. Buying up land also offered the ability to gain access to the water are other environmental resources linked to it. A new era of ‘land grabbing’ had begun.

Civil society groups working with people in rural areas raised the alarm. Governments parcelling out land to investors often claimed that it was vacant or owned by the state, but in many cases, supposedly ‘empty’ land was subject to customary rights, being used by shifting cultivators or pastoralists for example. In many countries, there is a strong need for investment in rural areas, but the people living there did not always appear to benefit, and could be evicted or rendered landless.

As land speculation continued, researchers at the STEPS Centre and elsewhere saw the need for in-depth and systematic enquiry into what was happening. Behind the alarming worldwide statistics, there was also a need to know what was happening on the ground.

Investigating claims about land grabs

In 2010, researchers from STEPS, along with institutes in the Netherlands, South Africa and the USA, helped to found the Land Deal Politics Initiative (LDPI).

The LDPI set out to address questions that could inform policies that would help rural poor people who were vulnerable to land grabs. Who was making these deals? Who were the winners and losers? What actors were involved, and what were they doing to each other? And how were changing environments and ecologies affecting these patterns, and being affected by them?

The LDPI’s first step was to provide small grants to early career researchers, particularly those from Africa, for fieldwork and writing on land deals. Researchers in the scheme produced 57 working papers on cases from around the world. This data was brought together in 2011 at the first international conference on Land Grabbing, held at the Institute of Development Studies at Sussex, with many papers being subsequently published in a range of journal articles and special issues.

This was followed in 2011 by the first international conference on Land Grabbing, hosted by the STEPS-affiliated Future Agricultures Consortium in the UK.

Olivier de Schutter, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, speaks at the first international conference on Land Grabbing, held at the Institute of Development Studies.

The conference brought together 180 people from around the globe, linking researchers with campaigning organisations and activists (including Oxfam, Via Campesina and Focus on the Global South) and policymakers from the World Bank, USAID, the European Union and the UK Government.

The conference brought to light the corruption and failures of large land deals to deliver on their promises, but also why it was difficult to count, track and document them — from secret contracts to failed or stalled projects.

A second conference, in 2012, came back to the debate, with a keynote speech from the Director-General of the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation, José Graziano da Silva (PDF).

This time, three big insights came to the fore.

The first was that land grabs had to be understood in the context of big structural, geopolitical issues, and changing power relations in countries themselves and worldwide — and longer histories of agrarian change. Land deals had not come out of nowhere. The second was that narratives like ‘idle land’ and ‘backward smallholders’ were being used, alongside techniques of counting, measurement and modelling, to influence what happened. The third was that land grabs were not instant — they often took place over quite long periods, in a variety of forms, with different impacts on different groups of people.

Not just land: ‘green grabs’ and ‘water grabs’

Land was being appropriated not just for food or fuel, but in the service of ‘green’ agendas: including conservation, biodiversity, ecotourism and biofuels. This built on long histories of colonial and neo-colonial capture of resources. But it now involved new forms of valuation, commodification and markets for pieces and aspects of nature, and an extraordinary new range of actors and alliances — such as pension funds and venture capitalists, commodity traders and consultants, business entrepreneurs, ecotourism companies and the military, green activists and anxious consumers.

In 2012, a special issue of the Journal of Peasant Studies, co-edited by James Fairhead, Melissa Leach and Ian Scoones, collected 17 case studies of green grabs from around the world. In Mozambique, a company was negotiating a lease with the government for 15 million hectares, or 19 per cent of the country’s surface — to gain land for trees that could be traded on global carbon markets. In Latin America, conservation agencies, ecotourism companies and the military were aligning to protect the Guatemalan Maya Biosphere Reserve as a “Maya-themed vacationland” to generate ecotourism profits, while assisting the government’s war on drugs and counter-insurgency. In the process, people were being violently excluded.

Another special issue, in Water Alternatives, drew attention to the neglected issue of water grabbing. It showed how a desire for water lay behind many ‘land grabs’, and how water’s very nature — fluid, variable and linked to farming, food, human health and energy production — made it difficult to assess the impacts of water grabs.

These examples represent the dark side of the green economy, where market-based mechanisms were intended to help sustainable development. In the worst cases, this was opening up ecosystems to be ‘asset-stripped’. The work on green and water grabbing helped to highlight the need for more transparency, consent and accountability, and the recognition of how local people valued and used natural resources.

Forests and Carbon: Win-win or a recipe for conflict?

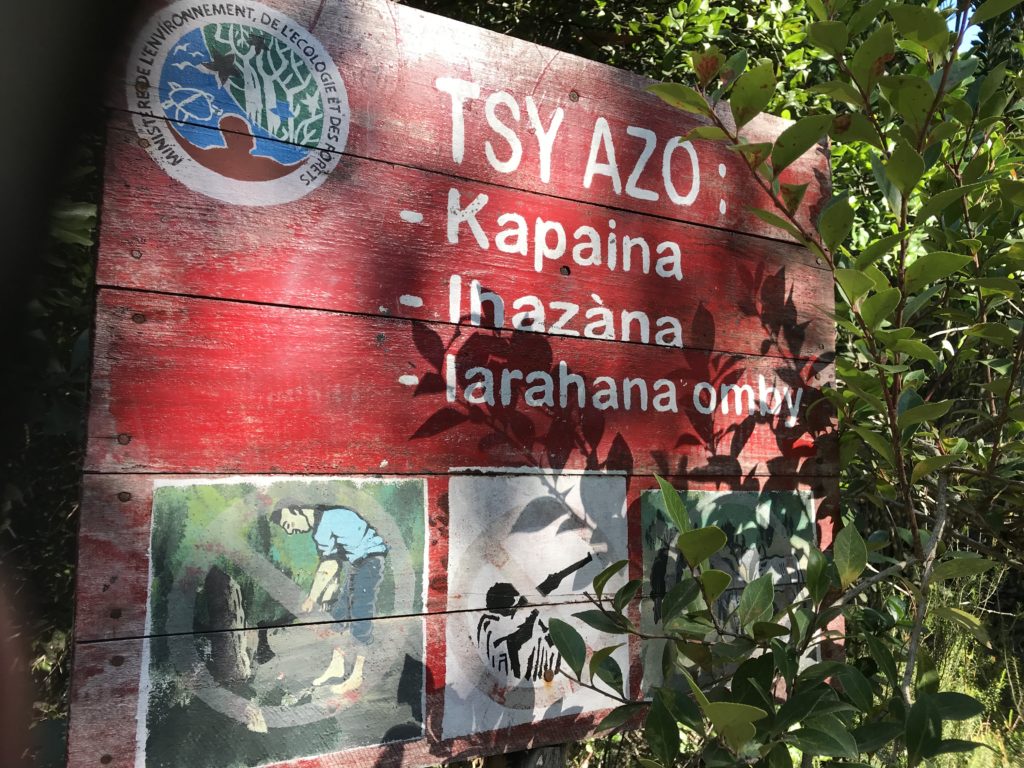

Meanwhile, a STEPS project focused on carbon forestry in Africa — another example of where the rights and livelihoods of local people can clash with big new initiatives. In this case, carbon emissions in the rich, industrialised parts of the world are offset by growing or maintaining forests in Africa. The schemes are also supposed to promote biodiversity and alleviate poverty, providing a ‘win-win’.

But the reality is often more complex. The STEPS research found that local people were often blamed for the destruction of forests, presented as a degradation from ‘natural’ environments. ‘Slash and burn’ farming is blamed even in areas where it is no longer practised.

The STEPS research showed how the carbon embedded in forests has become a commodity, managed through a highly technical set of mechanisms, schemes, measurements and exchanges, linked to UN initiatives to mitigate climate change like REDD (Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation). But these often come face to face with complicated histories in the places where the schemes are implemented.

For example, in Zimbabwe, a project developer, Carbon Green Africa, has allied in Hurungwe with local Korekore farmers and the Rural District Council, offering a range of benefits, including carbon dividends and ‘alternative livelihood’ projects in exchange for protecting forests, and planting trees. But the local farmers are pitched against other forces, including politically-connected tobacco farmers who came to the area in the 1980s and 1990s, and other displaced farmers after the 2000 land reform. Divisions based on ethnicity, class, gender, economic priority and more divide ‘the community’ that is notionally involved in the project.

Multiple conflicts like this have emerged between land owners, forest users and project developers. Achieving a neat, market-based solution to climate mitigation through forest carbon projects has not been straightforward.

The studies from the carbon project were among those presented in 2014 at Green Economy in the South, the first major international conference on the subject. The conference was held in Tanzania to make it more accessible for Southern-based scholars to attend. STEPS also provided a web platform for the conference. The event provided an antidote to Northern-led thinking on issues that affected people in the Global South.

STEPS Centre work on carbon politics continued with work on mangroves — a particularly important resource — in India, Kenya and Madagascar. The contested valuations between different actors — project developers, scientists, conservationists and local communities — mean that carbon projects are centrally a tussle about value: for whom, over what time frames and in relation to what criteria?

Resource Politics

The work on land, green grabbing and carbon forestry has all fed into a larger theme of ‘resource politics’.

The idea of ‘planetary boundaries’ as providing the limits of biophysical systems gained much purchase in policy debates, with human impacts being shown to have surpassed boundaries in a number of areas. Many began to talk about the ‘Anthropocene’ — a new geological age marked by the environmental change caused by humans. These ideas were hugely influential and therefore politically important, particularly around global discussions about the Sustainable Development Goals.

However, STEPS Centre researchers began to ask some critical questions. Could the ideas of the Anthropocene become a way to depoliticise struggles over resources? How were understandings about scarcity and limits framed, and by whom? Who was expected to ‘manage’ the global environment, set limits and halt environmental destruction? Was this a centralised vision of ‘cockpit’ control or a more caring, embedded approach led by different people in different places? And did debates about the Anthropocene pay enough attention to the unequal contributions of rich and poor to planetary decline and the consequences of unequal histories due to colonialism and underdevelopment?

Debates about planetary boundaries and the need to think more socially and politically about these questions have been central to many debates hosted by the STEPS Centre, from the debate between Melissa Leach and Johan Rockström in 2015 to the STEPS annual lecture by Kate Raworth in 2018.

The STEPS Centre’s e-learning course includes a module on Resource Politics with free video lectures and reading lists. The module reflects on the conflicts and tensions involved in resources, ‘nature’ and discourses of crisis, as well as drawing on STEPS thinking about the politics of financialisation and resource grabs.

Picking up on our long-term work on social and grassroots innovation, and along with the Stockholm Resilience Centre and the Tellus Institute, we also looked at how these urgent global environmental challenges required new approaches to innovation — approaches that would give far greater recognition and power to grassroots actors and processes.

Financialising nature and resource politics

In the face of urgent demands to decarbonise economies and protect ecosystems, a variety of mechanisms and instruments were being used to value nature in a way that could be meaningful for markets and investment. This meant that natural resources of all kinds could be treated as a financial asset or commodified.

For some, this was a necessary way to protect ecosystems and ensure their survival, recognising value or ‘natural capital’. From other, more critical perspectives, this process of commodification ignored other kinds of value, and threatened the rights, livelihoods and cultures of people who depended on them.

Questions are raised in particular about how value is generated and by whom. Much of this rests on assumptions of ‘scarcity’. But limits are always constructed in context and a social and political perspective highlights how processes of investment, resource grabbing and the commodification of aspects of nature are generated through competing knowledges and interests.

In 2015, the STEPS Centre co-convened a symposium on Critical Perspectives on the Financialisation of Nature, exploring how theory, politics and practical approaches could make sense of a growing number of market-based environmental products and services.

This theme was central to the international conference on Resource Politics that the Centre hosted at Sussex in 2015. This also explored a wider set of issues — including the meanings and implications of the Anthropocene, the role of social justice movements in environmental questions, contestations over notions of the ‘green economy’, feminist visions for sustainability, all illustrated and elaborated by many case studies of local initiatives, conflicts, mobilisations and alliances from around the world.

The 2015 conference also saw the launch of POLLEN (the Political Ecology Network), a growing and vibrant network of researchers and activists working on political ecology. Initially focused on Europe, the network has since expanded as interest in these themes has grown.

Contested Natures

In 2020, the STEPS Centre focused on the theme of Natures. This explored a series of urgent questions: How is talk of crisis shaping nature and people’s views of it? How can colonial forms of knowledge, technology and power be challenged, and what might it mean to decolonize the study of environmental change? What do alternatives look like, and how can we explore, nurture, imagine and live the relationships we might want for the future?

A series of essays, discussions and web comics explored the issues, including creative ways to think about Natures. This included an online public discussion with the makers of the Oscar-winning film My Octopus Teacher, on their unique approach to storytelling and documentary-making.

During the year, STEPS also co-hosted the POLLEN conference, this time online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and attracting over 1000 participants. Major plenary panels covered themes ranging from the Covid-19 pandemic to Black Ecologies, feminist ecology and the future of conservation, highlighting how debates had extended to new themes and audiences.

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/embed?listType=playlist&list=PLI8qkz1i11OT0kiSiHnjJCyuStGO4RKM_&v=g35TYf21JHY[/embedyt]

Playlist of the four plenaries of the POLLEN20 conference.

Over the past decade, the STEPS Centre’s work on resource politics has shown how the commodification of resources and the financialisation of nature has resulted in patterns of investment and expropriation that has dramatically affected landscapes across the world, unevenly affecting those who are already vulnerable and marginalised.

STEPS Centre work documenting cases, probing methodologies, convening events and providing analysis of emerging dynamics has contributed to a wider debate about how resource politics should be framed. But our work also uncovered new opportunities for alliances and methods between researchers, activists, communities and others to resist and challenge the way that resources were being debated, appropriated and used. Recognising the political nature of resources is an essential first step in this process.

Find out more

Stories of Change

From 2006-2021, the ESRC STEPS Centre explored pathways to sustainability – showing the important roles that marginalised ideas, knowledge and forms of action could play in responding to complex social, technological and environmental challenges.

In this process, we were involved in many process of change, from local struggles to high-level international debates. These Stories of Change explore some key themes from STEPS work, to share what we learned.