This is one of a series of Stories of Change from the ESRC STEPS Centre.

From different pathways for maize farmers, to debates around land grabbing, livestock, livelihoods and climate change, STEPS research has explored the complex politics of food around the world.

How are the different pathways for agriculture and food production constructed? Which ones dominate and which are more hidden?

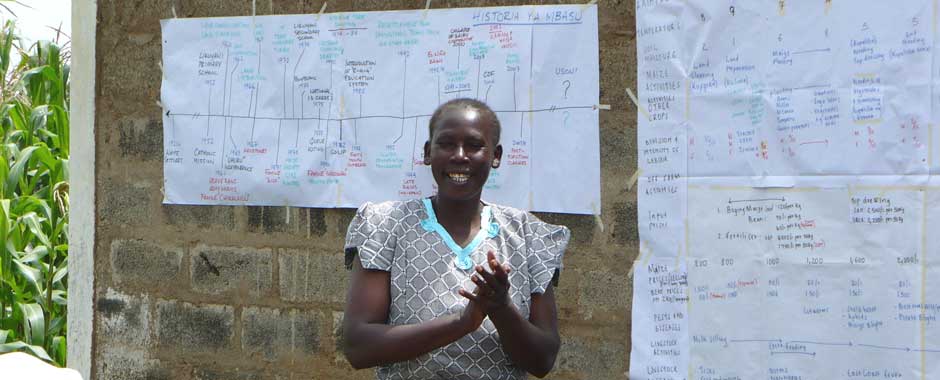

These were the questions that the STEPS Centre set out to explore in Kenya starting in 2006. The focus was maize – the dominant crop in many of the major food-growing regions – but the question quickly became which maize (local varieties, hybrids or genetically-modified alternatives)? And what about small grains, such as millets and sorghums, that complement the grain economy?

Delving into the different fieldwork settings, the team revealed a complex set of pathways. Choices of seeds depended on who you were, what resources you had, whether you had labour at home and your tastes and preferences for food. The pathways were dependent on wealth, on age, on gender and on occupation. There was no single pathway that was good for food security and sustainable agriculture.

These findings were shared through a Working Paper, a set of briefings and a short film with policymakers in Kenya.

In contrast to the often polarised arguments around genetically-modified crops or agroecology, for instance, there was clearly no single solution, no best option. It depended, but crucially it depended on politics and social relations. Those pushing ‘modern’ seeds had a particular agenda, trying to foster what they called a ‘green revolution’ for Africa, but were often blind to context, and pushed a technological, ideologically-driven vision of progress. This may be useful for some people, but not everyone, and perhaps especially those who they claimed to be supporting: poor and marginalised people.

The lessons from the ‘maize project’ (though it was on much more than maize) have informed work on agriculture and food in the STEPS Centre ever since.

Technology and agriculture

Building on work that started in the 1990s, before the establishment of the Centre, we created an archive of research and analysis on agricultural biotechnology, pulling together work by STEPS Centre researchers on themes such as poverty reduction and food security, regulating technologies and corporate control.

Regulating technologies in particular was a major theme of the Centre’s work for some years, examining the tensions between international harmonisation and local demands, needs and realities.

As agricultural technologies have changed, the archive includes new updates; for example on the role of genome editing technologies (including CRISPR) as a new approach for improving productivity. Over the years, we have contributed to various inquiries and debates, for example around the UK government’s consultation on genetic technologies or the European Union’s use of the precautionary principle in the regulation of GM crops.

Taking our critical perspectives on science and technology together with a concern with questions of ‘development’ has been the hallmark of STEPS work on this theme. Sally Brooks’ book – Rice Biofortification: Lessons for Global Science and Development – is an example of where a forensic look at technology development in agriculture sheds new light on what are seen as ‘magic bullet’ solutions to, in this case, nutritional deficits in rice-growing regions.

In the same way, Stephen Whitfield’s book – Adapting to Climate Uncertainty in African Agriculture: Narratives and Knowledge Politics – highlighted the debates around genetically-modified, drought-resistant maize in Kenya, looking critically at narratives around how technologies enhance adaptation to climate change.

In the same way, Stephen Whitfield’s book – Adapting to Climate Uncertainty in African Agriculture: Narratives and Knowledge Politics – highlighted the debates around genetically-modified, drought-resistant maize in Kenya, looking critically at narratives around how technologies enhance adaptation to climate change.

With development aid agendas firmly fixed on technological and market fix solutions to agricultural challenges, STEPS work has also taken a close look at funding approaches, and how technological imaginaries get wrapped up in particular development visions – for example around the ‘Green Revolution’. Work on ‘philanthrocapitalism’ for example took a look at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and its support for the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), established with a base in Nairobi in 2006.

Seeds and rights

STEPS America Latina, our hub based in Argentina, has taken work on rights over seeds much further through the work of Bioleft, exploring practical solutions on the ground.

Challenging the control of the seed system by large agri-businesses with proprietary rights (such as patents for seeds), Bioleft has developed new forms of agreement that allow for seed sharing and exchange, rooted in local agricultural systems, while protecting farmers’ rights.

Central to transformations in agriculture are brokering roles that allow different actors to connect in order to come up with new social and technical innovations. In a STEPS seminar, Anabel Marin explained how Bioleft began and the challenges it faces.

Sustainable local food systems require access to resources and markets. Attention therefore must extend way beyond technology to questions of land access and the politics of markets and consumption.

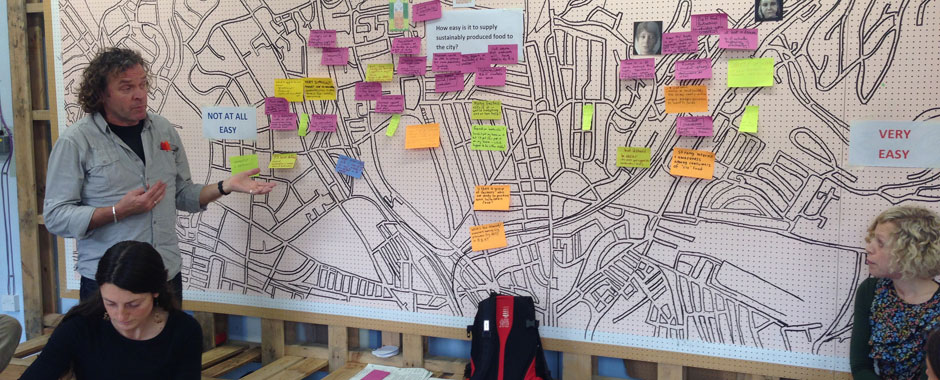

This was a key lesson from work in Brighton and Hove in the UK on food systems, where access to land in the estate owned by the Council around the city was a key issue constraining the opportunities for new forms of production, with potentials for shifting market dynamics and consumption patterns in the city.

Living with livestock

STEPS work has extended beyond crop agriculture to look at livestock. An early paper highlighted the health implications of the livestock revolution, through the massive expansion of livestock numbers, living in close proximity to humans. Zoonoses, antibiotic resistance and pollution are all major issues.

Our work on poultry farming in Ghana and pig farming in China (and later through an affiliate project, the Myanmar Pig Partnership) picked up on the challenges arising from the intensification of livestock production. In each case, our work explored more sustainable pathways that meet the challenges of intensification, while supporting diets and livelihoods.

More extensive livestock production has been the focus of work on pastoralism, linked initially to STEPS affiliate partner, the Future Agricultures Consortium, and now the ERC-funded programme, PASTRES.

The STEPS book Pastoralism and Development in Africa: Dynamic Change at the Margins pulled together reflections on the changing nature of pastoralism in the Greater Horn of Africa. Authors reflected on the findings in a short video.

This work led on to studies on land grabbing and extractivism in pastoral rangelands, as well as uncertainty and pastoralism in different contexts, through the TAPESTRY and PASTRES affiliated projects.

For example, our work highlighted debates around the link between livestock and climate change, the role of livestock as part of rural landscapes and the pressures on pastoralists from industrial development and changes in land use. For example, we have seen how camel herders in Gujarat have championed rare breeds and new products, in order to make the case to move around landscapes and produce food in traditional ways.

Arguments over Agronomy

Pathways to sustainable agricultural and food systems are complex – technologies, politics, social dynamics and environmental changes all influence which direction is taken. This was the lesson of the two conferences (and two books) on ‘Contested Agronomy’, raising major questions about funding priorities, research approaches and institutional architectures.

A more social and political perspective on agronomy – and more broadly the science of agriculture – is needed. This is an argument that is often resisted by mainstream agricultural science institutions, which frame the challenge simply as the linear ‘uptake’ of technologies, responding to ‘gaps’ in performance. Instead, making agronomy work for development requires a much more engaged, participatory approach, working with farmers’ own knowledge and approaches.

Contested Agronomy: Agricultural Research in a Changing World

Agronomy for Development: The Politics of Knowledge in Agricultural Research

Drawing together chapters from four STEPS Centre book, our open access book on ‘Pathways to Sustainable Agriculture’ highlighted three integrative themes that characterised STEPS Centre research over the years. These were framing (how we understand agriculture and its roles in development), practice (how agriculture and agricultural research is carried out, and by whom) and governance (how agriculture is regulated and controlled).

Agriculture is of course only one part of rural livelihoods, as work on ‘sustainable livelihoods’ has long pointed out.

And food is part of a wider ‘nexus’, connecting with water and energy, as explored in a book by Jeremy Allouche, Dipak Gyawali and Carl Middleton. Rather than just accumulating technical knowledge about the links between water, energy and food, it’s also important to understand how people experience or respond to this nexus in their own lives: for example, where a new hydroelectric dam affects how people fish and farm in the area around it.

Opening up food systems

Opening up food systems

Pressures and stresses on food systems are more hotly debated than ever. Consumption and diets are changing; concerns about food, climate change and disease have not gone away. More and more land, seeds and supply chains are vulnerable to control or capture by governments, corporations, funders and NGOs, sometimes working in unlikely alliances. But resistance is also strong – from international alliances of small food producers, to innovative projects like Bioleft, or local efforts to preserve traditional pastoral ways of life.

Understanding the complexity of agricultural and food systems is essential for informed policy and effective mobilisation and advocacy. Too often, however, debates are simplified and polarised. The STEPS Centre’s work has aimed to shed light on the nuances, and opens up discussions of alternatives that might otherwise be obscured.

Stories of Change

From 2006-2021, the ESRC STEPS Centre explored pathways to sustainability – showing the important roles that marginalised ideas, knowledge and forms of action could play in responding to complex social, technological and environmental challenges.

In this process, we were involved in many process of change, from local struggles to high-level international debates. These Stories of Change explore some key themes from STEPS work, to share what we learned.