Friday’s murderous attacks in Paris came just over two weeks before the start of the COP21 conference on climate change. A crisis meeting was held on Saturday morning to determine whether the event should go ahead, with a swift resolution to continue, under heightened security.

Christiana Figueres, the UNFCCC’s Executive Secretary, tweeted “Of course #COP21 proceeds as planned. Even more so now. #COP21 = respecting our differences & same time acting together collaboratively.”

If the aim of ISIS is to spread chaos, the most effective reaction may be to show the best of international efforts to work together. COPs may be messy, difficult, even often disappointing, but they represent the desire for nations to work together to improve human wellbeing.

But another, perhaps stronger, story is also in the air: the desire to connect climate and conflict.

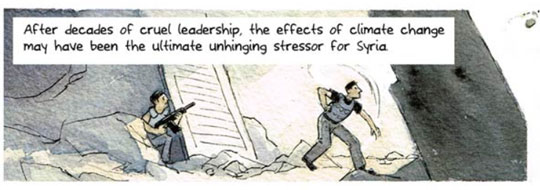

The US Presidential candidate Bernie Sanders said “Climate change is directly related to the growth of terrorism” in a debate on 14 November, provoking a flurry of responses in the media. He particularly invoked the CIA as a source. He was widely criticised for exaggerating the cause and effect, but he is not alone – many others have made the link, often referring back to a study that suggests a drought in Syria in 2006-2009 was due to climate change, and was a factor in the 2011 uprising. There’s even a beautifully-drawn, and widely-shared comic telling the story.

Perhaps it’s just that COP21 is high on the agenda, but it’s odd that some politicians are so keen to reiterate this link precisely now. Of all the factors that could have led up to the Paris attacks – and indeed the wider conflict – the climate link is tenuous at best. The drought may have been one trigger of many, but that doesn’t explain why this link is being made so strongly now.

One reason might be that in the search to explain the attacks, people are bound to reach for all theories and causes. Another might be that blaming climate change, at least in part, could be a useful distraction from addressing the other causes of instability in the Middle East.

But if you zoom out a little, this latest narrative is only part of a long history of linkages between security and the climate. The US military describes climate change as a ‘threat multiplier’. Richard A Matthew has traced the growing dialogue between environmentalists and the US military back several decades to the end of the Cold War.

Of course, soldiers are entitled to worry about all kinds of social and environmental factors that might make their lives more difficult – my point is about how this is picked up and internalised by the rest of us.

No doubt some of this rhetoric is about getting climate change on the agenda – of making people care, by linking it to fear and urgency, giving the world another reason to take action. It could even be seen as a crass competition to define what is the ‘greatest threat’ to humanity. But if so, it’s a risky strategy.

As climate change becomes framed as a quasi-military threat, policy on it becomes entangled with national security concerns. Actions become about locking down ‘energy security’ to reduce dependence on foreign nations. Defence becomes a disproportionately loud voice in discussions on why and how to make decisions on decarbonising the economy. As COP21 approaches, let’s hope that discussions about how nations can work together don’t get drowned out by a narrative based on fear.

This post is part of our coverage of the COP21 climate change conference.

Image: Symbolia, via Mother Jones

Comments are closed.