by Nathan Oxley, Jonathan Dolley, Shilpi Srivastava and Gordon McGranahan

This is one in a series of four blog posts exploring ideas and case studies on ‘transformations’, drawing on research carried out in 2017 and looking forward to the STEPS Centre’s work in 2018. For background and links to the other posts, read the introduction.

“One of the essential aspects of depression is the sense that you will always be mired in this misery, that nothing can or will change… There’s a public equivalent to private depression, in the sense that the nation or the society rather than the individual is stuck. Things don’t always change for the better, but they can change, and we can play a role in that change if we act. Which is where hope comes in, and memory, the collective memory we call history.”

Rebecca Solnit, from the introduction to ‘Hope in the Dark’, updated 2016 edition

The world never stays still. But in the face of severe or worrying social and environmental change, how can familiar systems, processes and politics be transformed for the better? Over the past year, the STEPS Centre has been studying transformations in cities, energy, food and the politics around different kinds of resources. We’ve been trying to understand how different people mobilise for more just and sustainable futures, and how they react to change too.

One of the things we’ve looked at is the crucial role of history in campaigns, debates and politics about social & environmental change.

So what can we say about the different ways that history is used, and how it shapes collective action? Anyone who’s been involved in such movements, or studied them, will recognise that stories and histories are important, but they often play different roles in different settings. Histories can build solidarity, back up claims for rights, evoke strong emotions, or help to understand different people’s points of view.

In this blog post, inspired by a conversation between the four of us in May 2017, we’ll look back at recent and ongoing STEPS research to illustrate how this works with some examples from different settings around the world.

What difference does history make?

Roughly speaking, we’ve identified four functions of history from our own studies. The lines between them are blurred, and this list isn’t exhaustive, but here’s what we noticed. We also realised that none of these uses of history comes without risk, so for each of them, we’ve tried to articulate what the potential downside could be.

- Storytelling is used to build a sense of solidarity within a group.

History can be a spark to inspire change. Examples from the past are often used to motivate people for certain kinds of action, often linked to values and beliefs.

Our recent booklet with the New Weather Institute, Rapid Transitions: how did we do that? deliberately dipped into history to find instances where radical changes have been quickly achieved. As the booklet acknowledges, this approach to history is selective: the point is to challenge the dominant narrative that ‘there’s nothing we can do’ or that change is too complicated to achieve.

The risk is that people only get a partial understanding of what happened, or that failures are glossed over and successes idealised. To counter this, it’s important to be honest about our aims, and seek to learn wider lessons, not treat examples as a model that can be plucked off the shelf and replicated. Even in a selective history, there needs to be an acknowledgement that there may be other interpretations of the story.

- History is used to legitimise a claim in a dispute.

In the STEPS project on the resource politics around mangroves in Kutch, India, we studied a coastal area with long-established mangroves that is now undergoing rapid industrial development and conservation efforts.

Conservationists seeking to protect the mangroves are coming into conflict with some local people who have historically depended on them. Local herders, who take care of the extraordinary swimming camels unique to the region, are pointing to their long history of using the mangroves as grazing grounds to stake their claim to the resource.

In this case, the downside is that for you to win the argument, your history needs to be viewed as valid evidence, alongside the other forms of evidence that are in play – science, economics and so on. And oral histories and traditions are sometimes not given the same weight as written documents.

- Learning from the past.

Those involved in tackling pollution or other urban problems may feel like they have to start from scratch to find solutions. But historical documents can show where others have succeeded or failed in the past.

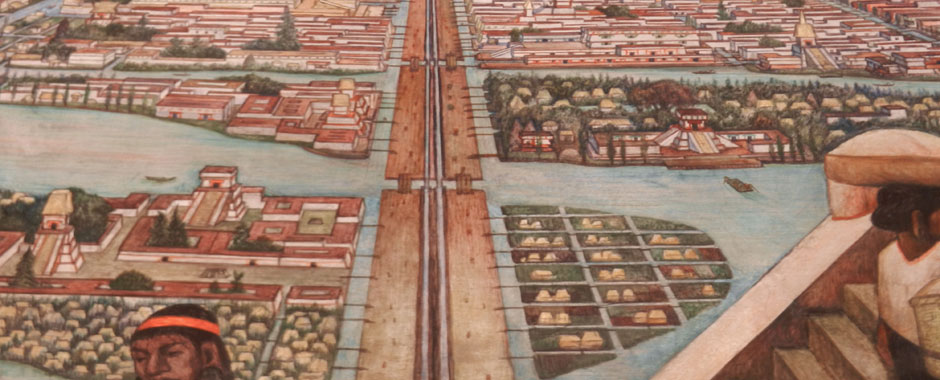

For example, in the lakes and canals of Xochimilco, Mexico City, the ‘Pathways Network’ project is working with local people to find responses to rapid urbanisation and pollution. At a meeting to discuss solutions, a participant brought along some old magazines which revealed that people had been trying to solve the same problem for decades. This gave the modern-day participants a connection to the past which moved them emotionally; but it also inspired them to focus on the barriers and obstacles which had prevented real change for many years.

There are risks here too. If we become fixated on past failures, it may seem as if the obstacles to change are too great. And stories from the past don’t always apply themselves neatly to modern circumstances.

- Looking at many histories.

Academics, in particular, can design their research so it examines plural histories. This means trying to uncover the stories of losers as well as winners – seeing things from several sides, to try to understand how different people interpreted events and used them in different ways as part of their own story.

This can even happen at a level that’s really personal and local. Methods like Life Histories can transform our view of a big story by focusing on an individual’s experience of it – for example, changing our view of familiar stories like those around Green Revolutions in the 1960s, or tell us about the motivations of people who got involved in environmental campaigns in Indian cities. Such approaches might help us to be more aware of uncertainties and surprises in the present and in the future, as we realise that the same events can be experienced in radically different ways by different groups of people.

But in focusing down too much on individuals we might lose sight of the wider picture; or in analysing multiple histories we may get bogged down in academic detail.

As we’ve discussed, these are just some of the ways that history can shape collective action and debates for more sustainable futures. But what’s the potential of these different functions of history to contribute to transformations that are caring and emancipatory, rather than oppressive?

Using history in transformative change

For example, our work on peri-urban environmental campaigns in India (see point 4 above) suggested that there were several people and groups with the potential to work together more closely. There has been some collaboration between them at different points, and they’ve been motivated for different reasons towards some shared goals. But there hasn’t been a unifying narrative, or a shared history that brought them together.

So could they start to build a stronger collective history – one that could be used to build solidarity and a sense of purpose? Could successful campaigns and moments of change be built, over time, into a wider story? There might be a role for researchers, who have the time to revisit old documents and talk to disparate groups as part of their studies, in helping this to happen.

Looking at these examples and the lessons from them, some observations emerge.

- There is no ‘best’ or single way to use history, and all of the uses that we describe above have risks. To reduce the impacts of these risks, it may help to be aware of the alternatives – for example, if you’re looking to tell stories about heroic achievements, be aware of the untold stories and the failures too.

- Histories often don’t work on their own – they can help to back up a certain course of action, but other forms of agency and power are required to make a change.

- Who gets to write history? It matters which histories come to dominate, and which ones get left unsaid. There are sometimes unconscious, sometimes deliberate choices made about which stories to listen to – for example, the role of women or minorities is often underplayed in stories about a nation’s history. Looking at what didn’t happen – experiments that failed, or ‘what if’ – can help to challenge the notion that our current circumstances were inevitable all along.

- Even if we can learn much from the past, there are also moments of serendipity. There are times when things happen that you never expected, and circumstances transform radically beyond our control. Recognising when this happens might mean adopting new responses to change.

- Big mobilisations create their own histories which then get adopted and used in different ways. Is what we’re doing now part of a future history? How will it be told by those who come after us?

Faced with a series of social and environmental stresses and shocks, there are urgent calls for radical, systemic change. But, as past and present experience show, this can take many forms. What does it take to make sustainability transformations emancipatory (caring), rather than repressive (controlling)?

Faced with a series of social and environmental stresses and shocks, there are urgent calls for radical, systemic change. But, as past and present experience show, this can take many forms. What does it take to make sustainability transformations emancipatory (caring), rather than repressive (controlling)?

Find out more about our theme for 2018 on our Transformations theme page.