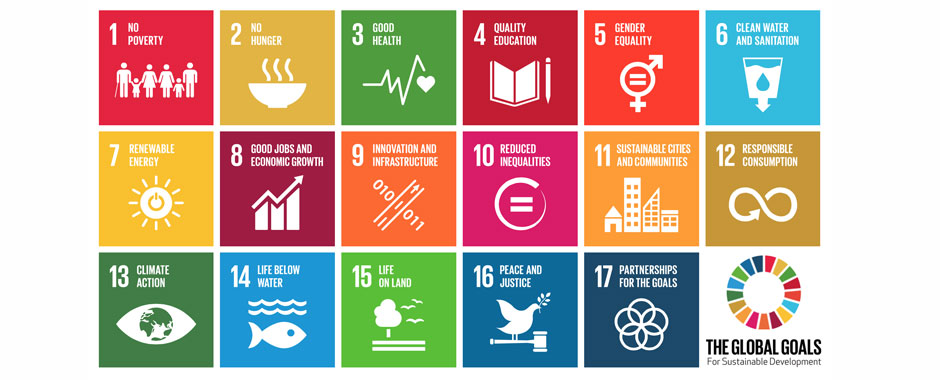

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were launched with great fanfare in September 2015. This was an ambitious agenda for the whole world, aiming to transform development towards sustainability, while leaving no-one behind.

I was excited by the prospects. Back then, I expressed the hope that this was perhaps the moment when a new politics of sustainability, linking across plural goals, could be realised. Maybe the SDGs could be the much-needed platform for connecting diverse local initiatives in radical transformation, adding up across the world.

Taking stock

What has happened since? While there are many great efforts that link to the SDGs, offering real hope for the future, the overall process seems to have been bogged down in reporting against the plethora of targets and indicators. At national level, the grip of siloed, sectoral processes has undermined the potential for a truly integrative approach.

This is illustrated starkly by the UK’s response. Led by the Department for International Development and coordinated by the Cabinet Office, the corporate report offers a long list of initiatives from different government departments. There seems to be no vision for radical transformation to sustainability. The UK will present its national voluntary report to the UN in July and belatedly there has been a flurry of consultations. But it all seems a bit limited and late, as several parliamentary inquires have pointed out.

A politics of transformation?

The UK is not alone in this. Many countries are not seeing the SDGs as the platform for new approaches to sustainable development that they should be. There are exceptions of course. Costa Rica, for example, has launched its Green New Deal, and its president (and IDS alumnus), Carlos Alvarado, recently wrote in the Financial Times that shifting to a low carbon economy had to be transformational, and could not be incremental.

He is right of course. And this means challenging incumbent power, policy innovation and bottom up action all at the same time. This is what transformations to sustainability entail, as we describe in a recent STEPS paper. This requires a new politics – from the bottom and from the top. The UK government has of course been preoccupied with the self-imposed chaos that is Brexit, while many others are focused on narrow incrementalism, without a vision for how transformational change can happen.

In the years since the SDGs were launched, the political environment has changed dramatically. The rise of nationalist, authoritarian, populist regimes means that the sort of internationalist coalitions, rooted in an emancipatory politics, that are required for addressing sustainability are more difficult to form, and nationalist concerns get priority.

Integrative approaches: moving beyond the sectoral default

Yet, it isn’t just the political environment that is constraining this broader vision. The bureaucratic default of narrow, sectoral approaches is repeated again and again. So much of the debate about the SDGs focuses on single goals, or limited ‘synergies’, rather than seeing them as a radical menu for a plural approach to radical transformation.

Professional and funding siloes reinforce this, and the integrative, systemic, holistic response that is needed to carve out pathways to sustainability is missed. This is a familiar complaint about development in general of course.

And it recalls earlier discussions about how to create frameworks for more integrative development thinking and action. Over 20 years ago, I was involved in the intense debate that emerged about ‘sustainable livelihoods’ approaches.

In 1998, we produced a framework that was widely adopted by development agencies. In the process of implementation, it was much abused and it encountered many problems. But at least it was an attempt to encourage cross-sectoral interaction, linked to located, bottom-up processes of change, and it captured the imaginations of many.

Strangely, there doesn’t seem to be any equivalent linked to the SDGs. As I argued in a recent Sussex Development Lecture, I believe a revival of livelihoods thinking is urgently needed if the SDGs are to realise their important ambitions.

Looking back, the original sustainable livelihoods framework has many limitations, something I pointed out in my 2015 book, Sustainable Livelihoods and Rural Development. The book, discussed in an IDS podcast out this month, reflected back on livelihoods approaches in order to look forward towards a more politically-informed approach, linking locality-specific livelihoods analysis to wider structural, political economy perspectives.

At the Sussex lecture, I asked the audience if they’d heard of sustainable livelihoods approaches. A few had, but there was a definite generational bias among those who raised their hands. The faddism of development is such that frameworks and approaches come and go.

Even at IDS, where much of this thinking originated, sustainable livelihoods perspectives are no longer taught centrally as part of the many Masters’ courses. At one level, this shouldn’t matter. Each period needs to develop approaches that suit the times. But there is a problem if important insights and useful tools are just forgotten and have to be reinvented afresh.

Rescuing the SDGs: it’s not too late!

As I said during the lecture, we have to rescue the SDGs “a graveyard of technocratic-bureaucratic-instrumental approaches” – and this means injecting a more integrated and political dimension into our thinking and practice. Otherwise, the sort of radical sustainability transformations that are needed will not happen.

The good news is that we have some of the tools – and much past experience too. Repurposing and revitalising the sustainable livelihoods approach for the SDGs seems a good place to start – and 2030 is still a way off yet!

This article was first posted on the IDS website.

Related content

Feature: Why politics matters for transformations to sustainability

Sustainable Livelihoods: ‘Between the Lines’ podcast with Ian Scoones