by Shiara González, Lakshmi Charli-Joseph, and Beth Tellman

The Wixáritari communities, better known as Huichol, are mainly located within the Sierra Madre Occidental, north of Jalisco state, Mexico. These communities, like many others in the world, and particularly in the Americas, are subject to pressures from the ‘Western’ world which are the catalyst for many changes. A few weeks ago, we visited two of these communities (La Cebolleta and La Laguna) where Shiara is doing her PhD research. Our objective was to engage in two participatory mapping workshops with Huichol women to understand how their communities have changed over time.

Although the other two of us (Beth and Lakshmi) focus on change in urban areas in Mexico City, what really unites all of our work at the most basic level, and perhaps even sustainability science as a whole, is the study of change. How and why does the world change? Whom does change benefit? What changes should be resisted or accepted, and what are the possible consequences of either strategy? How does culture, gender, generation, and other expressions of identity inform each person’s position and perspective?

Vulnerability, adaptation, transformation, resilience and many of the key themes in sustainability science are perhaps just different ways of studying and expressing change in a social-ecological system.

For 8 years Shiara has volunteered with groups of NGOs who collaborate in a project called Ha ta tukari (‘water, our life’), including Isla Urbana, Proyecto ConcentrArte, Taller Luum and IRRI Mexico. Among other activities, this group has been installing rainwater systems for communities, saving them labour and improving their health and sanitation.

But to focus only on the impacts of water on these communities is to ignore the context in which this intervention occurs: a social-ecological system that is constantly changing. What is the role of water relative to other changes in the community? Since Shiara works on sustainability science (and not in a hydrology program) it requires a more systematic and holistic understanding through which water intervention operates.

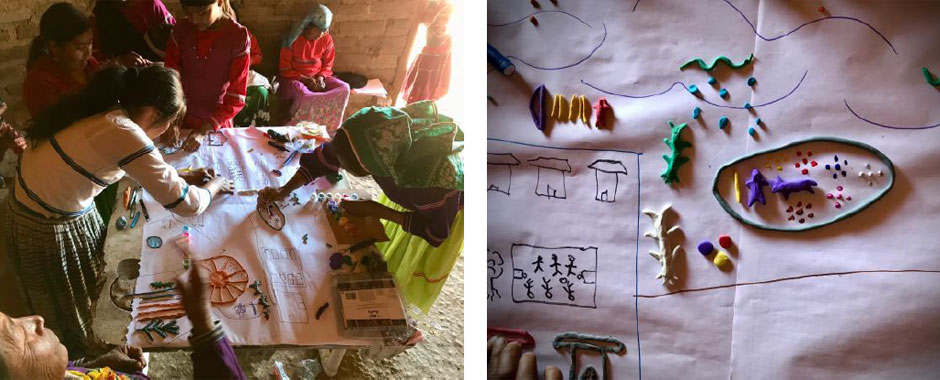

As Spanish is not the first language for these women (and many speak little to no Spanish) we did not want to run a typical conversation-based focus group. We opted instead for non-verbal methods of expressing change. We used clay and paint to depict a ‘map’ of the community today, focusing on the most important elements as a springboard to discuss what parts of the ‘map’ have changed over the years. We covered up or modified elements of the map to represent this change. The women conveyed what they saw as the most positive and negative changes, as well as what has persisted over time.

As Spanish is not the first language for these women (and many speak little to no Spanish) we did not want to run a typical conversation-based focus group. We opted instead for non-verbal methods of expressing change. We used clay and paint to depict a ‘map’ of the community today, focusing on the most important elements as a springboard to discuss what parts of the ‘map’ have changed over the years. We covered up or modified elements of the map to represent this change. The women conveyed what they saw as the most positive and negative changes, as well as what has persisted over time.

Through this process, the communities pointed out major changes in migration, electricity, customs/culture, reduction in rainfall, the introduction of formalized education, shifts in cultivation practices, the arrival of western medicine, and more. What surprised us was the diversity between the two communities, and the responses that challenged our conception of what constitutes ‘progress’. For example, neither community mentioned western medicine as particularly important or transformative.

One community talked about the arrival of electricity very negatively, because of its impact on the family. Several women noticed that their children were so focused on cellphones and TV that families had lost the custom of evening conversation. This seems to be one of the many changes that influence young people to lose interest in cumpliendo el costumbre, or ‘practising’ traditional customs.

The importance of ‘el Costumbre’ (the religious cosmo-vision of the Huicholes) is based on the notion of very close and direct reciprocal relationships between people and nature. This (very Mesoamerican) practice revolves around the idea that natural spirits provide sustenance and health, and people repay them with offerings and sacrifices.

The practice of el Costumbre was apparent throughout the workshops, particularly in one community. For example, both communities drew corn in 5 colors, and one older woman (who could not speak Spanish) even drew the rain god who had saved the 5 colors of corn from a flood at the top of the map during our discussion. The loss of el Costumbre seemed to be of primary concern to many women. The introduction of formal education, increasing migration to cities, and government programs that introduce more cash into the community all seem to culminate in affecting this central aspect of Huichol culture, being, life, and meaning.

Every night over our bonfire we would discuss what we saw, heard, and learned, reflecting on our years in post-graduate education on sustainability. Traditional measures of development and progress like those outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals – access to electricity, formalized education, western health and medicine – may not indicate ‘progress’ or development to some of the Huichol women we spoke with. This is not to say the women who raised these concerns necessarily reject these changes. But the ‘benefits’ of such change are more nuanced than a PhD student educated from a Western perspective may stop to reflect upon.

Shiara’s contribution ultimately may reach far beyond what we learned about water access in the Sierra Huichol, and help us think deeper about key concepts in sustainability from another perspective. Studying change is not just about a deep focus on one phenomenon. It’s about understanding the relationships and roles in a larger social-ecological system that has evolved over time, is evolving now, and will continue to do so.

All three of us are interested in transformation: taking deliberate steps towards more sustainable social-ecological systems. But this experience made us question the meaning of transformation in this context. What deliberate changes would these women, individually or collectively, like to see or make – and what is their desire or agency to do so? What is the meaning of transformation for the indigenous women who attended the workshops? How can those perspectives and voices inform theoretical debates we are used to writing about at ASU and UNAM?

About the authors

Shiara is a PhD candidate in the graduate program of Sustainability Sciences, UNAM, Mexico City. Her PhD thesis focuses on the impact of the introduction of rain water systems in two Huichol communities in Jalisco, Mexico.

Lakshmi is a PhD candidate in the graduate program of Sustainability Sciences, UNAM, Mexico City. Her PhD thesis is about exploring transdisciplinary methods to identify and promote individual and collective agency in the Xochimilco urban wetland of Mexico City.

Beth is a PhD candidate in the School of Geographical Science and Urban Planning, Arizona State University (ASU). Her PhD work focuses on exploring the socio-political dynamics affecting land use change and urbanization in Mexico City.

Faced with a series of social and environmental stresses and shocks, there are urgent calls for radical, systemic change. But, as past and present experience show, this can take many forms. What does it take to make sustainability transformations emancipatory (caring), rather than repressive (controlling)?

Faced with a series of social and environmental stresses and shocks, there are urgent calls for radical, systemic change. But, as past and present experience show, this can take many forms. What does it take to make sustainability transformations emancipatory (caring), rather than repressive (controlling)?

Find out more about our theme for 2018 on our Transformations theme page.