Depending who and where you are in the world, you will be experiencing the effects of climate change differently. Here in the UK, the recent hot-weather days in February might have felt unsettling, even as your body welcomed the warmth and sunshine. Meanwhile, people in some parts of the United States were caught in freezing winter storms, with businesses closed, and people stuck in homes without power. Elsewhere, in Kutch, in the Indian State of Gujurat, local people currently are struggling to maintain their livelihoods, having seen only 26 per cent of its 30-year annual average rainfall.

We are living on a planet that is increasingly unfamiliar to us, but not all experiences of uncertainty are the same. How do different people around the world experience these various anomalies, oddities and uncertainties, which are often linked to global climate change? While social and natural scientists, modellers, and other experts have developed sophisticated theories of ecological uncertainty, these theories, models and diagrams from ‘above’ may have little to do with the everyday experiences of climate uncertainty of men and women (poor or rich, urban or rural, especially in the global South) on the ground.

Sites of uncertainty in cities are also sites of personal, collective and political struggle. People in more marginalised situations are on the front line of many uncertainties, caused by climate change and also other threats – think of the Grenfell tragedy in West London. They are also threatened by fast-moving developments and land grabs. They often see and feel uncertainties in a really different way to how experts and governments think about them.

How might all this affect the way we think about and imagine future systems? This week in the System Change Hive, Lyla Mehta (IDS/STEPS Centre) talked to the Hive about her research on climate change uncertainties, and her most recent TAPESTRY research project, which explores how transformation may arise ‘from below’ in marginal environments with high levels of uncertainty. Her talk focused on her work in urban and peri-urban areas in India. Here is something of what we learned.

Uncertainty and Climate Change in Mumbai

Mumbai is a mega coastal city in western India that has been largely reclaimed from the sea. The city is likely to be affected by climate change-related uncertainties associated with sea-level rise, extreme rainfall events and changes in ocean surface temperature. About 50 per cent of people in this diverse and cosmopolitan city are poor and residing along the coast or in ecologically vulnerable spaces near creeks and drains.

To the west of this ‘maximum city’, where the city meets the Arabian Sea, there is a place called Versova. It’s a Koliwada, a community of the traditional Koli fishers of Mumbai, one of several which pre-date the massive urban development that now surrounds them. Koli fishers and their families are used to living with uncertainty, but times are getting harder in many ways. The creek that flows through Versova into the sea once was navigable by bigger boats, but now seems to have shrunk. It is clogged with plastic waste and other consumer debris. The expanding city is affecting the currents which bring fish near to the shore.

Koli livelihoods are defined by their ability to adapt and respond to the wind and rain, the habits and movements of fish, the flows and fluctuations of prices and markets. Up to a point, uncertainty is a defining feature of their way of lives and identities, but there is a limit even to what they can withstand; romantic notions aside, the new and more rapid environmental changes make things especially difficult, causing anxiety and fear.

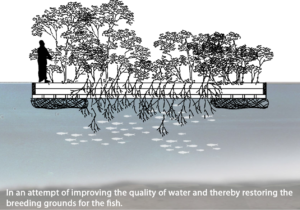

Faced with these hardships, alliances have been forged in Versova between progressive state agencies, civil society and citizen groups (both rich and poor), to re-imagine their coastal ecosystems by focusing on mangrove restoration, sustainable water and waste management, as well as ways to strengthen the city’s capacity to adapt to disasters and climate change. People have also been asserting the need to protect the livelihoods of vulnerable social groups that live on the city’s margins.

Lyla shared an example of one such alliance. Bombay 61, a group of urban designers and architects, with members originally from the Koli community, has worked with fishers to design solutions to some of the immediate problems they face. These include using nets to catch the plastic that clogs up Versova creek, the waterway that leads from the city into the sea. Plastic could also be a resource to add buoyancy to new small boats or rafts, cheap to assemble and repurpose. The project has, to some extent, been putting change in the hands of the Koli community.

Uncertainty is not in all cases a problem to be removed, reduced or managed from ‘above’. A virtue of many marginalised communities is their ability to respond to environmental uncertainties themselves. Some situations, such as climate change, however, throw up extremely challenging circumstances where radically new systems are needed. The communities themselves must be involved in determining that change, if it’s to meet their needs while also addressing the problem.

‘Systems Change not Climate Change’

In light of this, we might ask, do we want systems to be flexible, adaptive and informal, or formal, clear and secure? Do we want a combination of all of these things? When a city gets redesigned, what happens to the slums or the people on the edge? When new laws or currencies come along, how do people in communities relate to them?

This doesn’t only apply to India – in the UK or Europe we might think of travellers, refugees, undocumented people, homeless people, or those who choose to live by different rules. Are systems being designed with them, for them, around them or in spite of them? Can we put ourselves in their shoes and imagine how they might want to transform the systems that are all around them? What would happen if we were to listen to what they think and feel about the systems that impact their lives?