This is the second in a pair of blog posts focusing on tree planting, climate change and biodiversity. Read the first here.

The first phase of the delayed Biodiversity Convention of the Parties (COP15) concludes today. In advance of the climate COP in Glasgow in November, there has been much talk of linking the twin crises of biodiversity and the climate. But what does this imply for those on the front-line of ambitious conservation plans?

Grand objectives for protecting 30% of the planet by 2030 have been hailed, with dozens of countries backing the High Ambition Coalition for Nature and People, co-chaired by Costa Rica, France and the UK. Amongst all the policy buzzwords, so-called ‘nature-based solutions’ and ‘offsets’ are all the rage, central to a proposed Global Biodiversity Framework to be agreed as part of the second phase of the biodiversity COP process next year. What does all this mean in practice, and is it a good idea?

As discussed in an earlier PASTRES blog, massive tree planting schemes with huge targets for areas to be covered, are being suggested as a central component of these proposals. Linking nature conservation with climate change, these are frequently supported through significant new finance for ‘offset’ schemes to meet net-zero obligations. These are vigorously backed by powerful international conservation organisations in alliance with big business, sometimes the worst fossil fuel polluters themselves.

Carbon offsetting and tree planting: a perfect solution?

Carbon offsetting through tree planting sounds like a win-win neat solution to the climate and biodiversity crises. It’s simple, they say: you give carbon a price; you plant trees or pay for them to be protected through a scheme in a far-off place; those involved in the scheme claim the credits and make a bit of money, while areas are protected and biodiversity improved. And then you can say you have offset your carbon footprint and feel much better about your green credentials, continuing with business as usual.

Many argue that such a market mechanism is a vital route to achieving ‘net-zero’ targets and meeting the Paris Agreement commitments. Mark Carney, the former Bank of England boss, has recently produced a plan to increase the scale of the voluntary carbon market to US$100 billion a year (up from $300 million), and it’s backed by the great and the good of business and finance. This will, he argues, expand access to the carbon market, enhance market integrity, improve its governance through improved standards and so help reduce net emissions and mitigate climate change.

Well, as ever, it’s not so simple, as Greenpeace and others have pointed out.

Carbon conflicts

Some years ago as part of some ESRC STEPS Centre work, together with colleagues from across Africa, we set out to look at some early carbon forestry schemes, many under the banner of the UN REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) programme, most linked to nascent voluntary carbon markets. Some of these were in dryland areas, where extensive livestock production was central to local livelihoods. In Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Sierra Leone Zambia and Zimbabwe, we expected to find a diversity of experiences: some working, some not, with room for improvement. But the tale sadly was fairly universally depressing.

There were many problems, all discussed in our book, ‘Carbon Conflicts and Forest Landscapes in Africa’. The ‘baseline’ reference areas chosen were often inappropriate; the areas protected (loss avoided) were large and meant that if not being completely excluded, people had to change their use of these areas; alternative livelihood projects that were meant to replace supposedly damaging land uses were inadequate; the credits earned gained were minimal (the carbon price was very low at the time) and the bureaucratic processes involved in counting and calculating carbon losses and benefits made money for consultants and the project managers, but with little local effect.

In other words, the ideals on the brochures and websites – and the claims made to the assessors and purchasers of credits – were not realised on the ground.

The problems with carbon forestry

Since then, the critique of carbon forestry has grown, with wider assessments in the academic literature of many projects showing broadly similar patterns. Interrogating the disjuncture between the claims of success and the failures on the ground, Adeniyi Asiyanbi and Jens Friis Lund argue that REDD+ projects have become ‘too big to fail’ as they have become so interlinked with a global commitment to offsetting as a ‘green fix’, even as such projects become rebranded as ‘Natural Climate Solutions’ or ‘Nature-Based Solutions’.

The counter-argument, offered by the voluntary carbon market advocates, is that these are just teething problems, that a more regulated market and more rigorous standards and guarantees would eliminate the sharks, and leakage effects and ‘non-permanence’ of projects could be insured against through having ‘buffer pools’ of credits that are never sold. Promoters of such approaches argue passionately that avoiding forest loss and conserving carbon – however and wherever it’s done – must be a good thing given the climate emergency.

Well, only up to a point. In a number of the cases we studied, there were real questions as to whether carbon was even being conserved at all, as the leakage effects were so large and the dodgy baselines so misleading.

There is a wider argument too. Although most of these schemes did not involve a significant amount of tree planting, but only woodland regeneration of existing stock, for most of our study areas – savannah environments with patches of woodland and grass – ‘protecting’ such areas from human use and grazing by pastoralists and other livestock keepers is actually, in important respects, ‘unnatural’.

As discussed in an earlier blogpost, these are anthropogenic landscapes created by thousands of years of use by wildlife, domestic livestock and humans, with the effects of controlled fire being vital for ecosystem health. Carbon is cycled and preserved in such ecosystems as part of use, and such use offsets the real risks of catastrophic loss of carbon through wildfire if land is ‘protected’, and so has a huge build-up of flammable material (something that happened in a few of our cases, and has been feature of recent wildfires around the world).

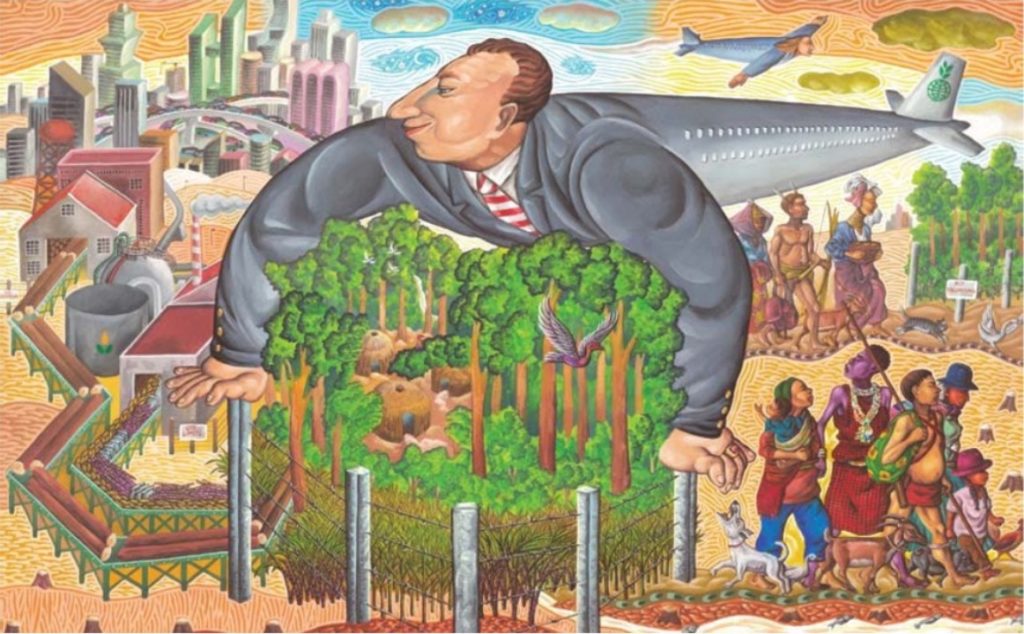

Some object to the commodification of carbon and the financialisation of conservation, full stop. The commodification of nature, it is argued, generates distortions in favour of capital and against people, in turn undermine local efforts to tackle climate change. As Amber Huff argues, there is inevitably a mismatch between the promises of market environmentalism through the creation of ideal-type carbon markets and the messy realities on the ground, generating a whole range of frictions and political contests.

Making profits from nature also results in processes of exclusion, as the easiest way to claim credits is to ‘farm’ carbon in plantations. This process of ‘green grabbing’ is certainly part of the carbon forestry drive, accelerating as the carbon price increases and the incentives to invest heighten. The boom in offsetting projects also brings many players often with little knowledge of complexities of forestry projects across the world.

Myths of carbon equivalence

Even if market mechanisms didn’t have such mismatches and distortions (which is of course rather unlikely), there is a further basic question. Making carbon equivalent across different types of emission/sequestration processes is the basic requirement of a carbon market. But does this make scientific sense in terms of reducing emissions?

Carbon emitted through burning fossil fuels is not the same as carbon in a forest. They are part of two different carbon cycles – one very slow (the geological cycle) and one relatively fast (the biological cycle). Trees – and other ‘nature-based solutions’ – are part of the fast cycle, and carbon can be both replaced and lost, for example through fires. For fossil fuels it’s basically best not to burn them in the first place – and thus, as the slogan goes: keep coal in the hole.

There are other reasons to challenge the idea of carbon equivalence, this time more from a justice and ethics perspective. Emissions from air travel or driving a SUV are not the same as emissions from, say, agriculture generating food security in a poor part of the world. For the same reason, emissions from industrial farming of meat or milk is not the same as the production of such products from extensive, pastoral livestock production. As we argue in the recent PASTRES report, there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ forms of carbon in emissions and a justice and ethical perspective needs to differentiate these, just as a scientific approach needs to distinguish carbon in different cycles.

For all these reasons and more, we need to question the assumptions behind the equivalence of different types of carbon in offsetting schemes and carbon markets.

Sustainable pathways

In the build-up to COP26, great store is being set by ‘net-zero’ commitments, with offsetting through a massively expanded voluntary carbon market seen as very much part of the package. But such net-zero commitments may be misleading, even dangerous. They may not tackle the core problem of reducing emissions and may undermine the livelihoods of those living in often poor and marginalised settings – such as pastoralists in extensive rangelands – where carbon projects are introduced, with the result that exclusions are generated and ecologies are upset.

By salving the consciences of the ‘polluter elite’ amongst northern publics and global businesses, the real problems are not tackled, which must be to reduce carbon use and seek other, more sustainable pathways for economic development, such as extensive livestock production and mobile pastoralism, that are not so damaging to the planet.

This blogpost is the second of two articles focusing on tree planting around the COP15 biodiversity conference.

Related content

Is mass tree-planting the answer to biodiversity and climate challenges?