This is the (slightly edited) text of my talk at Communicate 2013, in a session called “liberating stories”. The pictures are some of the slides I used. The brief was to provide some suggestions about the role of the social sciences in ‘liberating stories’ for environmental communicators, through memorable examples. I only had 10 minutes so had to simplify a lot of things, but I’ve provided links in the text below, which you can follow to read about the proper, full description of the research and its findings.

We use big stories to make sense of a world that is increasingly complex and changing very fast and where everything seems to be chaotic. The climate’s changing, we need to feed more people than ever, demand for electricity is growing massively. And I think sometimes big stories are used to reassure people that someone’s in charge.

So we’re told we need to ‘tackle climate change’ by giving huge areas of land over to biofuels, or that questioning GM crops is ‘anti-science’ or ‘anti-progress’, or that large-scale industrial agriculture is the way to feed the world, and so on, and so on, and so on. There is a certain type of powerful story that likes you to think that it’s not a story at all.

When we hear these big stories being repeated as fact, when sustainability is just presented as a technical issue, or a scientific problem to be solved by experts, I think a massive alarm bell should ring. A sustainability klaxon, if you like.

I am interested in how we can tell different stories – little stories – that can challenge some of these assumptions about the way the world should be.

The STEPS Centre does this by working with poor and marginalised people in developing countries and looking at the different possible futures that they can see for themselves.

Water in peri-urban in India

There’s a STEPS project which looked at people on the edge of Delhi in India, in an industrial town called Ghaziabad that’s changed a lot in a very short space of time. The problem there is poor people are not getting access to water, or to clean water.

So the big official story in Delhi is the government is providing ‘access for all’ in the context of scarce water supply.

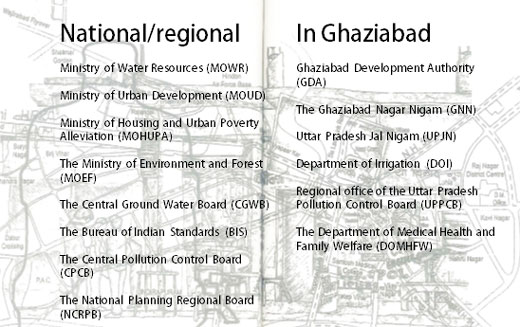

Through the research you see there’s a spider’s web of agencies that are supposed to deal with this. The problem is they don’t work together well, they’re not equipped to deal with things like inequality, informality and rapid change, as well as corruption and politics.

So you get this situation where there might be a massive water pipe running right through a poor area which might not even be on the map, on the way to the middle-class areas. People are having to run across a railway to get to the nearest pump and getting hurt.

So what about the little stories here?

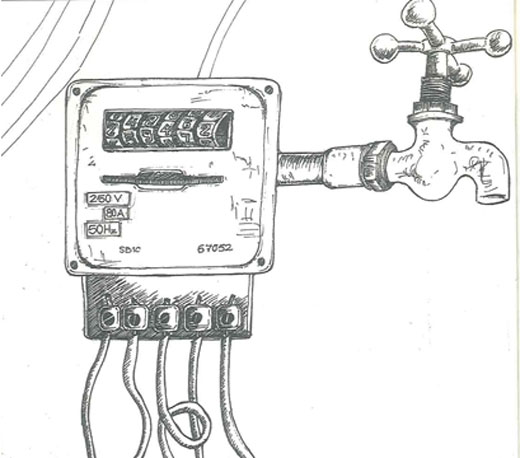

There’s the ingenuity of people illegally tapping the water supply, building their own DIY irrigation systems. But there’s also pollution and illness. And also a lot of everyday life revolves around water, and there’s also a whole set of beliefs and stories about water as well – for example, it’s central to the mythology of various religions.

Photo: Pritpal Randhawa

So exposing the big story and telling these little stories creates a disruption, so it’s easier to put your finger on what the problem is and start doing something about it. So in this project we used film and photos, and a mini-graphic novel as well as more traditional research publications to tell these stories.

Picture from The Water Cookbook by Bhagwati Prasad

I love this description about the task of sociology of scientific knowledge (SSK) by Prof Sheila Jasanoff: “to render more visible the connections and the unseen patterns that modern societies have taken pains to conceal”. There’s the idea that it’s actually quite important for those in power to try and disguise certain stories and certain connections – to pretend that they don’t exist.

What is it for example, about the story of inevitable progress towards large-scale industrial agriculture, enhanced by biotechnology and supported by corporate investment, that makes it such an attractive solution for agricultural development in Africa, and who wins and who loses from this story?

Maize in Kenya

Here’s another example from the STEPS Centre. It’s about climate change and crops in Kenya, where there have been a lot of droughts in the last couple of decades. The big story there is that science and technology will fix the problem, that scientists will deliver new drought-tolerant seeds to poor farmers through a kind of pipeline, where farmers are the end customers.

Photo: Sally Brooks

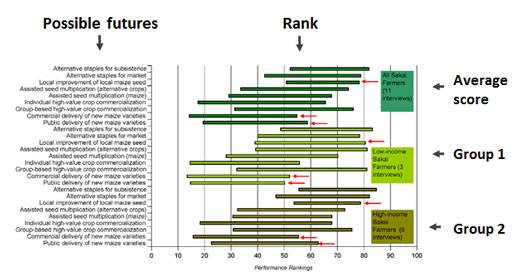

What our project did was go to some small farmers in a very dry region called Sakai, where they farm maize, and we listened to their stories and looked at how they actually make choices about which seeds or crops to use, how that fits with their daily life.

We used a technique called Multi Criteria Mapping to identify the farmers’ criteria for making their choices, like how important is the cost of seed, vs. how important is cooking, for your selection of crop. And we asked them to think about what they could do differently in response to all these droughts, and to rank the different futures that they imagined for themselves.

And then we compared this data from the small farmers, we compared it to what lots of other different groups thought the farmers should be doing – seed companies, scientists, policy makers etc. and what they thought the criteria were. And the stories were different, the little stories started to challenge the bigger story that everyone thought was obvious.

There’s a new section on the STEPS website all about methods which will explain how it works in more detail, and explains some other methods too.

The power of little stories

By comparing and exposing these stories we are saying: the big story is not the only game in town. There are always other pathways and other possibilities – however much some people would like to deny them, and it starts with listening to people and taking them seriously.

Stories don’t operate in a vacuum. These big stories are swimming in a sea of institutions and social and environmental change, shaped by politics and power. So in this context telling a different story is a profoundly political act.

When we see these big stories we need to look at who is winning and losing, we need to broaden out the debate about the future to include more people, more kinds of knowledge. It’s not only more fun and more interesting, I think you get a better result.

- Communicate conference website

- STEPS project on peri-urban sustainability in India

- STEPS project on environmental change and maize innovation in Kenya