by Hans Nicolai Adam and Synne Movik

As the world stares at alarming evidence of climate change impacts, the search for ‘big bang’ solutions remains challenging. The situation requires nothing short of an unprecedented transformation to a low-carbon society, on the heels of decades of polluting growth. The disappointing outcomes of the COP 25 in Madrid demonstrate how much-needed action can get bogged down by uncertainty and controversy. While it is tempting to despair, taking a historical perspective helps us to appreciate how transformations of this scale are not the result of an orchestrated endeavour, but a complex combination of many factors over a long time span.

Uncharted territories

There is little evidence to suggest that mitigative action on climate change is on track to stay within the threshold of a 1.5 C warming target, and the scale and pace of change needed to limit global warming the challenges. Greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) need to peak globally and ideally reduce within this decade to avoid crossing dangerous warming thresholds. Can such a transformation be directed and achieved in time? And how? These are key questions when charting a way forward.

Considering the ambitions and hopes for concrete steps and targets to stave off catastrophic climate change, the lack of agreement on comprehensive climate policy and action from the COP 25 were understandably met with a sense of despair. Even the Secretary General of the UN remarked that the ‘international community lost an important opportunity to show increased ambition on mitigation, adaptation & finance to tackle the climate crisis’. Culprits responsible for this stalemate are easily identified – they include big business, populist governments, major emitting countries, climate change deniers and other partisan interests.

In many ways, we currently find ourselves in unchartered territory. However, in searching for a more nuanced ‘big picture’ vantage point, one that moves beyond the symptomatic climate negotiations, it is worth turning to history for insights, specifically to the industrial revolution.

The shape of change under industrialisation

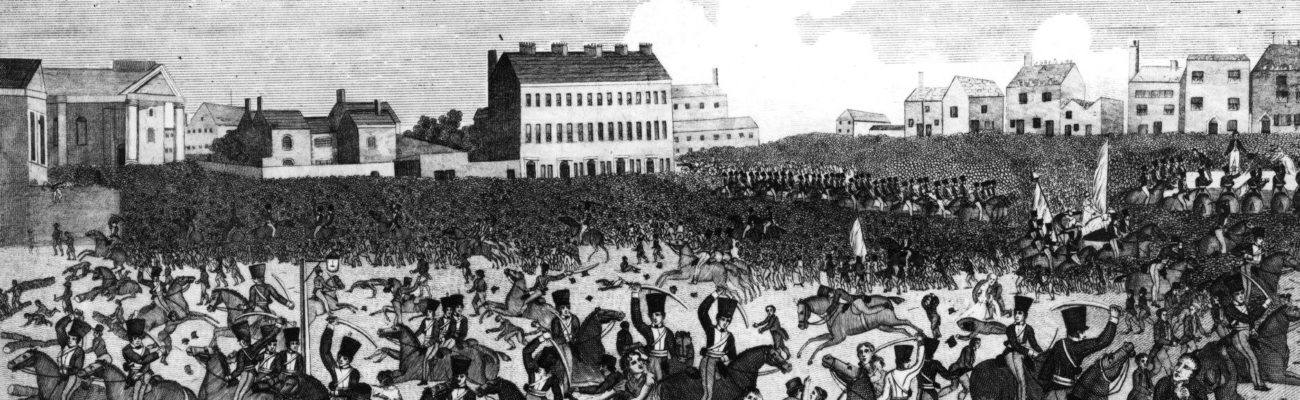

The history of industrialisation holds lessons on how large-scale change has unfolded, particularly relating to questions of intention, drivers and timescale. This period was marked by tremendous upheaval. It was not a well thought-through endeavour that had a clear beginning and end (with the exception of symbolic pointers, such as the introduction of the first steam engine in Great Britain in the 18th century). Rather, it was a fluid and complex combination of many factors, which provided oxygen to budding industries and economic growth. The introduction of disruptive technologies in energy, communication and transport, new models of governance, laws, and institutions, as well as changes in worldviews and associated value systems (the Enlightenment) coalesced to unleash new productive forces. This was not an intentional process orchestrated at a global scale in any meaningful way.

Nor was the industrial project geographically homogeneous or linear in progress. It spanned multiple generations over decades, producing discontent, winners and losers. Poor living and working conditions accompanied forceful uprooting and selective discrimination, in addition to conflict and the subjugation of entire continents to capture markets and resources. Contested ideas on the merits of an industrial society were ever present with questions of equality, freedom and justice – all key concerns for the utopians, communists and liberals contending for ideological dominance.

The shape of transformation today?

Contemporary concerns over climate change, regarding the role of technology, free markets, justice and values, resonate with those from the industrial revolution . The hopeful prospect of technological breakthroughs, legislative caps on GHG emissions, the use of market instruments or establishment of new governance regimes intersect with questions of environmental justice and values. With additional requirements of urgency (pace and scale), the global negotiations become a loaded and complex exercise. This makes it difficult to conceive of a ‘pathbreaking’ and ‘radical’ treaty that meets the hopes and expectations of a concerned public.

The industrial revolution is the last precursor of major societal change comparative in scope and scale to the transformation required today. What lesson can be learned from it for today, then? The failure to arrive at a decisive global agreement on climate change should not be mistaken as an obstacle towards meaningful or effective climate action per se. While despair is understandable, we should take heed of how, historically, global-scale transformation has not occurred simply from forcefully coordinated top-down mechanisms, but from a range of contested, deliberative, messy processes. It is unrealistic to expect a societal transformation to be driven by a singular process. The UNFCCC negotiations are thus but one piece – albeit an important and visible one – of a larger puzzle of societal change already underway, and should be viewed as such, without discrediting or hyping it.

Why wait for global consensus or grandiose visions to initiate action when changes happening in societies right now might also offer a way forward? Despite setbacks, such as the US exit from the Paris Agreement and continued contentions around scientific evidence, there are a plethora of initiatives exploring a range of practical options. Galvanized by a burden of scientific evidence and the increasingly visible impact of destructive natural disasters, climate change concerns inspire growing public interest and engagement. From social movements like ‘Fridays for Future’ or ‘Extinction Rebellion’, electoral manifestos of mainstream political parties, to green policy initiatives of major GHG emitters, diverse initiatives and strategies that involve business, governments and civil society abound. Technological applications in carbon sequestration, carbon capture and storage, energy usage, transport or recycling as well as ecologically sensitive farming practices are all under consideration.

There is evidence, then, that numerous incremental steps and a diversity of options are already available, practised, and being forged. We know that the industrial revolution was not a clean, linear or homogeneous phenomenon. It was ambiguous and sometimes contradictory, unfolding in fits and starts. Similarly, many of the options under consideration today are dogged by dilemmas about their merits and adverse consequences. For instance, debates continue over whether nuclear energy generation be strengthened.

Urgent (but careful) action is needed

In light of these contested issues, it is necessary to ensure that today’s actions to mitigate the worst effects of climate change do not undercut future flexibility, forestall alternatives or be harmful in other social or ecological spheres. We don’t know how successful a coming transformation will be in staving off the worst impacts from climate change. We do know that the industrial revolution bequeathed us today’s global environmental crisis and industrialisation needs either to be re-imagined or brought to ‘closure’ in response to calls for an end to environmentally destructive and extractive practices.

Climate change will precipitate enormous changes to our resource-intensive economies and way of life. The global climate negotiations will invariably be part of these changes, and public engagement and support remains crucial. The question of urgency, crisis and time constraint should, however, not mislead us into the temptation for autocratic or technological utopia. It is tempting to place disproportionate or exclusive emphasis on technical solutions, or hierarchical and top-down decision making, because they promise quick and easy solutions. Yet they can also forestall more democratic, diverse and socially just alternatives. These alternatives are important when we consider the breadth of social, cultural and economic dimensions that need to accompany a more durable and inclusive climate-related transformation. As was the case in the industrial revolution, there is no ‘single approach’ or miraculous policy. A multitude of factors flow together to bring about change.

Trial and experimentation without ‘locking in’ development pathways are thus prudent and necessary. A ‘tunnel vision’ on the other hand will be counterproductive. Beyond material action, fundamental re-considerations of what we value culturally or how we can distribute resources more equally need to invigorate and guide policy and public debate – a debate that has already gained traction concerning what really constitutes prosperity and well-being.

As we look ahead to another COP (this year’s COP26 in November, to be hosted in Glasgow), we should keep in mind that despite the disappointing outcomes of global negotiations, these should not detract from the immense possibilities that diverse, deliberative actions and activities hold in providing a way forward.

About the authors

Hans Nicolai Adam is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute for Water Research, NIVA, Oslo, Norway.

Synne Movik is an associate professor (faculty of landscape and society) at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

READ MORE

The authors are co-investigator on the TAPESTRY project, which examines how transformation may arise ‘from below’ in marginal environments with high levels of uncertainty, and how this could be scaled up and out.

STEPS has published a range of resources, such as blog posts, publications and videos, on the theme of Transformations. Find a selection of them, here.

Blog post: ‘Net zero and low-carbon transformation: Why targets are not enough‘ by Nathan Oxley