This is one of a series of Stories of Change from the ESRC STEPS Centre.

To pursue sustainable futures, transformation is needed – not just incremental shifts or policy transitions. We explored what this means in practice, recognising the role of politics, social justice and confronting incumbent power.

Pathways to sustainability look very different depending on who you are and where you stand. The early phases of the STEPS Centre’s work emphasised the contrasts of these different standpoints, particularly seen through struggles over knowledge and politics.

Uncovering alternative, hidden pathways was a central part of this, whether working on agriculture and food production in Kenya or peri-urban water use and pollution in India.

But it’s not enough to understand different perspectives. Moving from diagnosis to action has required a greater attention to the politics of transformation. How can changes occur from mainstream, dominant pathways, framed and supported by the powerful, to alternative, subaltern pathways, which benefit the marginalised?

Questions of politics, social justice and confronting incumbent power are central. This is much more than just engineering policy transitions or designing incentives to shift institutions at the margins.

In most cases, transformations to sustainability require much more radical change. This means challenging the structures that generate patterns of unsustainability. These are formed and reinforced by long histories of capitalism, colonialism and political marginalisation.

Our work on transformations — as a central theme of the past years of STEPS Centre work — has had to encompass a much more political stance, bringing basic questions of political economy to the centre of our analysis of pathways, and to how action for change is envisaged.

Our book The Politics of Green Transformations was part of this conversation, outlining how transformations emerge in context through state, market, technology and citizen-led transformations, frequently combined at particular moments.

For example, how do you challenge the hegemony of fossil fuel dependence to tackle climate change? Not only is state regulation of polluting companies needed, but also technological innovation and market incentives that generate alternatives. But none of this happens without mobilisations by citizens demanding change.

Whether we are talking about global issues or very local questions of sustainability, say around water pollution in a peri-urban area of Delhi, a political analysis of green transformations is key. This goes way beyond the simplistic rhetoric of appeals to a ‘green economy’ or ‘green transitions’, which assumes change happens simply through technical policy shifts.

the pathways network: from ideas to action

Translating these ideas into action was central to the collaborative work with the STEPS Centre’s Pathways to Sustainability Global Consortium after 2016.

Supported by the International Science Council, the ‘Pathways Network’ research project worked with local communities, field-based practitioners and policy-makers in China, Mexico, India, Argentina, Kenya and the UK on themes of food and agriculture, water pollution, low-carbon energy and industrial transitions.

In each case, a transdisciplinary, action-oriented approach was forged, aimed at ‘co-constructing’ alternatives with people in different contexts.

We found that finding ways forward towards alternative pathways depends in particular on how ‘sustainability’ is framed and what diverse, alternative pathways are imagined by different people.

Urban water in Gurgaon

For example, through participatory work with the Gurgaon Water Forum in India, the imaginations, values and interests of public administrators, resident welfare associations and citizen groups were explored together, resulting in discussions about the way urban planning and governance could be transformed.

Pressure on such processes is exerted by alliances of citizen environmentalists who are addressing toxic pollution using both legal activism and community monitoring. As a result alignments between activists and some within the state or business are opening up opportunities for transformation.

Challenges for Xochimilco’s wetlands

In the Xochimilco wetland in Mexico, farmers see challenges of sustainability emerging because of the decline in their traditional systems of land use and the commodification of the area by elites from outside the area.

Transformation is therefore about resistance in the face of powerful elites and state development plans. Spaces for change, however, were identified, resulting from changes in political leadership in Mexico City and their adoption of different platforms for planning. Alliance-building around these new spaces was therefore key to effecting sustainable transformations.

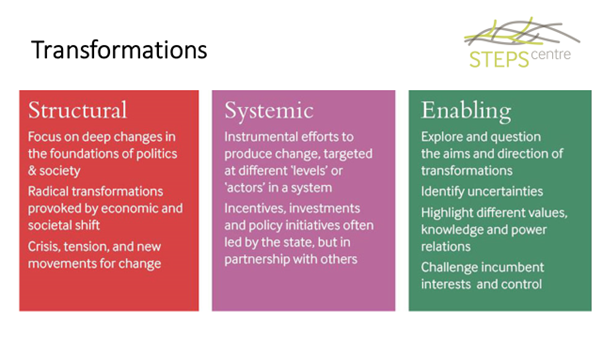

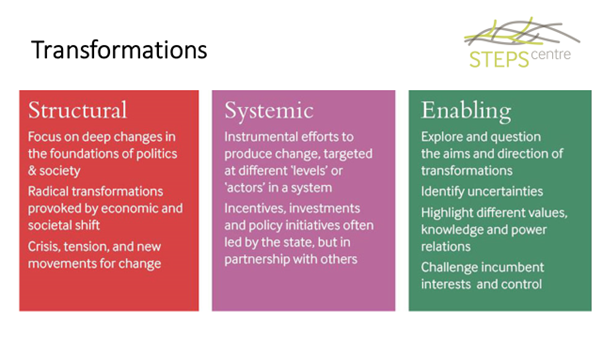

Across cases that STEPS Centre Consortium hubs and partners worked on, transformation was seen to emerge from a combination of structural change (challenging incumbent power, inequality and marginalisation), systemic change (engaging with policymaking processes), and enabling change (organising and mobilisation amongst citizens to exert collective pressure on those in power, and opening up possibilities for and imaginations of alternatives).

Changing seed systems in Argentina

In Argentina, STEPS America Latina researchers and partners worked with farmers, agribusinesses, regulators and technologists among others on transformations in the food and farming system. In Argentina this is currently dominated by input-intensive, polluting industrial farming, reliant on a limited range of often patented technologies.

Through discussions across actors, transformation was seen to rely on protecting and expanding agricultural diversity, so as to retain and enhance a range of alternative technologies and working practices within the system. These provide the basis for experimentation with less input-intensive and more socially-inclusive and productive agricultural systems.

Systemic shifts towards open source legal rules for seed innovation and co-operative business models and fair-trade certifications were identified as important ways forward. These can in turn have wider structural effects, helping to reconfigure the wider political economic structures of food and farming. Such licenses are in turn more accessible to economically-marginal farmers and avoid the exclusions of patent-based rules for innovation.

New institutional arrangements can help form bridges between players concerned about the agri-food system from different positions. New people, ideas and practices are brought together to generate a novel politics of transformation around seed production and associated farming systems, which has been mobilised through the Bioleft initiative that followed on from this research engagement.

In 2021, after years of work on the project, insights were brought together in an edited volume, co-written by people from all of the institutions involved in the Pathways Network. In the book, they reflected on the work in each study site, the methods used, and the dynamics of working together and learning from each other.

Transformative Pathways to Sustainability: Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts

lessons on enabling transformations

What lessons do we learn from these experiences (and others) for facilitating transformations to sustainability?

Diversity

A central one is the need to take diverse knowledges seriously. Different perspectives, rooted in different worldviews, values, moral positions and knowledges, compete in any process of transformation. Avoiding homogenising it into a singular view of progress, driven by a narrow expert-led sustainability science, is crucial.

This is more than incorporating ‘indigenous’ or ‘lay’ knowledges, but is about combining diverse sources of knowledge, which can emerge through interactions problems, priorities and plans are negotiated. This is the essence of transdisciplinarity, where multiple forms of expertise co-construct new knowledges that are both broader in what they consider and more open in their implications for change.

Politics

As we learned through all the action-research projects across the world, processes of co-construction are intensely political. This is more than ‘getting people around a table’ to engineer consensus. Of course, such processes will differ, depending on the political opportunities and costs and social-cultural contexts. We found that for scientists and practitioners — including STEPS researchers — such approaches require a change of roles, embracing positions that emphasise facilitation, “brokering” and convening, rather than solely knowledge production or policy implementation.

Plurality

Central to such dialogues is the need to take plural pathways seriously. No matter what the context is, there is never only one possible pathway. We learned how engagement must occur not just with diverse ideas, but also with the contrasting norms, interests and practices of different actors, making approaches such as multi-criteria mapping and participatory scenario workshops especially useful.

In our work across sites, we adapted the idea of ‘transformation labs’ (T-labs), which can help mobilise people and action around a problem, giving opportunities for learning and reflexivity in exploring divergent perspectives.

What this entails in the UK will be quite different to what such a process looks like in China, given cultural, social and political contexts.

For example, in the Xochimilco wetland in Mexico, our work explored the tensions between clean water, farmers’ livelihoods, tourism and urban development. The project created the space to confront and discuss assumptions from different actors (whether local farmers or external investors). We asked which pathway — of many possibilities — will be most successful for whom and why.

a politics of care

All this means that taking politics seriously is crucial, no matter how well-assisted by technical and policy expertise.

Negotiations among contending knowledges and divergent interests across multiple actors inevitably involves politics. But we found that taking an enabling approach — facilitated through transdisciplinary research and action — means a focus on agency and the capacities of actors to open up opportunities through forms of social innovation, often in surprising tactical alliances, creating a new politics for transformation. Taking politics seriously emphasises ‘political rigour’ — where diverse peoples and knowledges challenge prevailing power relations in collective political interventions.

A narrow control-oriented approach to sustainability transitions fails to address these wider political questions at the heart of the challenges of transformation. In contrast, an enabling approach, rooted in an ethic of ‘care’ and ‘conviviality’, drawing from diverse knowledge and accepting the plurality of pathways, offers a more positive and productive approach to generating alternative pathways to sustainability.

This is not easy, and it takes time – and it requires a deeply embedded and committed approach. But without such attention to the politics of sustainability, the grand goals and multiple targets of global ambitions will not be achieved.

Find out more

Stories of Change

From 2006-2021, the ESRC STEPS Centre explored pathways to sustainability – showing the important roles that marginalised ideas, knowledge and forms of action could play in responding to complex social, technological and environmental challenges.

In this process, we were involved in many process of change, from local struggles to high-level international debates. These Stories of Change explore some key themes from STEPS work, to share what we learned.