This is one of a series of Stories of Change from the ESRC STEPS Centre.

STEPS work on cities has shown how marginalised zones and excluded groups could play a more central role in sustainable urban futures.

How can cities and other urban areas meet the challenges of sustainability and justice? This question has been at the heart of the STEPS Centre since our first research projects started in 2011.

STEPS research began by asking what happens at the edges. You can think of the peri-urban as the zone at the edge, where the city meets the countryside. But peri-urban areas are often sites where a great deal of change is happening. They are sites where there are flows of people and materials and ideas. They are places in transition which have a crucial role to play in paving the way to more sustainable urban futures.

Life at the edge in Delhi

Around the megacity of Delhi, the peri-urban is a zone at the edge, where people live, pursuing farming and other livelihoods, and interacting with the city in different ways.

It’s also an interface where people and goods flow; complex rules govern access to space and resources. Planning authorities have overlapping responsibilities for vital resources like land, water or sanitation. Activists and NGOs debate about how best to support local people, with apparent tensions between agendas that prioritise the poor and those that prioritise the environment.

In 2007, the STEPS project on the peri-urban interface and sustainability of south Asian cities set out to explore what was happening in these areas, by working with communities in and around Delhi, and focusing on particular peri-urban systems.

A key question was which planning priorities come to dominate and why; and what this meant for various social and ecological processes, and for particular groups of poor and marginalised people. How was sustainability (or the lack of it) institutionalized in the peri-urban, and how could decision-making be opened up to include knowledge and groups that had been neglected?

Urbanisation in Asia: the peri-urban interface and sustainability of south Asian cities

Fieldwork in Delhi was carried out with desk research, focus groups and multi criteria mapping. Peri-urban areas had been thought of by some as merely transitional spaces, but our engagements raised the profile of peri-urban sustainability as a key issue, encouraging NGOs and activists to incorporate them into work programmes.

One of these issues was sustainable water management. Access and quality had been treated as separate issues, and formal policies had not recognised the links between health, water quality and agriculture.

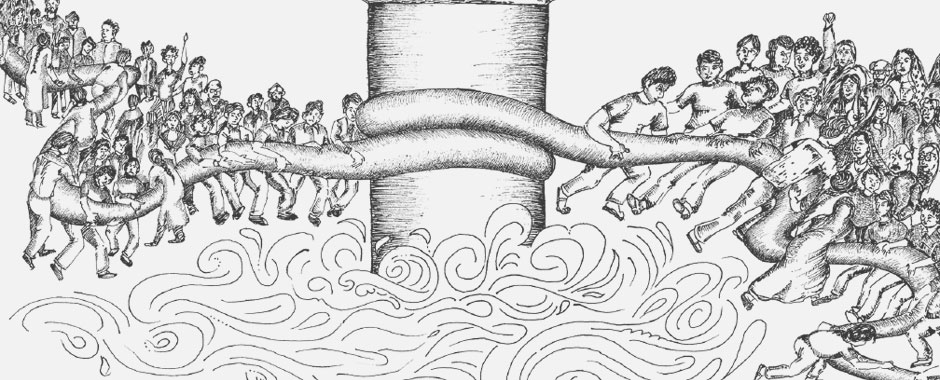

The study showed the importance of making these connections in peri-urban settings. It also explored how people got access to water through informal – even illegal – means, such as tapping into pipelines carrying water to richer areas. Fieldwork revealed not only contestation, but also cooperation across the formal and informal water regimes, revealing possibility for future interventions.

These issues of access, health, justice, informality and formality, efficiency and governance would be essential in thinking through alternative pathways to sustainability; a series of workshops raised this issue among academics from diverse disciplines, NGOs, government officials, activists and the media.

Spreading the word

At the case study sites in peri-urban Delhi and Ghaziabad, relationships were developed which have been key to a long term programme of transdisciplinary action research which is concerned with the role of the peri-urban in transformations to urban sustainability.

To reach out to a wider audience, a film was created showing the experiences of different people involved in peri-urban water issues – from tapping the water supply, to using water in farming, and campaigning for access to cleaner supplies.

An article in the Guardian highlighted the need for the Rio+20 sustainable development conference to pay attention to people in peri-urban areas. And a graphic novel supported by the project, The Water Cookbook, connected these issues to deeply running stories from Hindu mythology and culture. The graphic novel was created by Bhagwati Prasad (from Sarai, a project partner) through close interaction with peri-urban dwellers, and was distributed to schools, activists, academics and artists engaged in environment and justice issues.

Linking environment and health in the city

The first peri-urban project had drawn attention to the links between health and the environment in urban spaces. In 2011, the STEPS Centre supported research to explore the relationships between environmental degradation associated with rapid urban and industrial development, health and social justice. Once again, the project focused on urban places in India, with partners from JNU (Jawaharlal Nehru University), and Toxicslink, an NGO with a focus on spreading awareness on environmental health.

The project asked what environmental health threats affected people in ‘transitional spaces’ in cities, and why policy makers paid little attention to them. What policies and measures could make peri-urban places healthier for the people who lived in them?

One key piece of the puzzle was how to handle the solid waste that was thrown out every day by millions of households and businesses. At the time, the dominant pathway was to build more incineration plants to turn waste into energy. The downsides included air pollution for those living near plants; the policy also undermined the livelihoods of informal waste-pickers who collected and sorted rubbish for reuse or recycling. The action research process involved interviews and policy analysis, researchers from our project accompanied waste-pickers on their rounds, and used photo mapping to document routine practices on the ground.

Led by our partner Toxicslink, the team filed objections to a key piece of national legislation on solid waste management in India – the MSW rules. They were then invited to part of small committee charged with making amendments to the rules. The new 2016 rules recognise, in a limited way, the alternatives to a narrow centralised approach to handling waste; acknowledging the central role of the informal sector and the importance of localised initiatives to handle degradable waste.

To help with this, the project drew eight principles to be considered by policy for dialogue with stakeholders. We pointed out that waste flows were much more complicated than was recognised by the formal system, and that health risks were present throughout the journey of waste around the system – from collection, to dumping, segregation, recycling, waste treatment, and disposal. Centralising and privatising waste was favoured by authorities, but alternatives needed to be considered – including local composting of some waste, and learning from other cities where waste-pickers were working alongside larger-scale collections.

Working closely with waste pickers associations in Delhi, the initiative was able to help to bring together perspectives from groups that had previously focussed on environmental or livelihood concerns separately. Together they explored new approaches and practices in the day-to-day collection and processing of waste. As the lead of one large waste pickers’ association explained about the project:

“We are more mindful of the fact that segregation and recycling is not only a beneficial activity for these [informal waste] workers but is also an important environmental intervention for the entire city.”

Another commented:

“Now we are involved in implementing successful initiatives on decentralised composting with informal waste workers, municipal bodies and resident welfare associations. We have seven such projects and plan to expand.”

Read the story: Waste not, want not

The working lives of India’s urban waste pickers show the hidden connections between everything that matters in the city.

Ecosystems and the city

From 2014-2017, a STEPS-affiliated project explored how peri-urban ecosystems matter for people who live in and around cities, and for the policies that govern them. Th research asked how urban development processes can re connect with green landscapes and ecosystems in ways that will benefit everyone.

The cities of Delhi and Ghaziabad were expanding. But in between, people in villages were continuing to farm land in what were now peri-urban areas. The research asked what forms of agriculture could be good (or bad) for ecosystems, livelihoods and poverty alleviation. The project also looked at what this meant for the resilience of nearby cities. Peri-urban agriculture is a crucial source of affordable, nutritious food, but it also helps to recycle urban waste, mitigate the risks of floods, and reduce the effects of urban heat islands.

One of the research sites was the village of Karhera, in between Delhi and Ghaziabad. The project worked with local people to map changes in how land was used there, and who was winning or losing out in the process of urbanisation. They compared these findings with assumptions made by formal maps, policies and plans.

They also documented changes in farming livelihoods, and explored the risks to their ways of life. These included river pollution, industrial development, and the establishment of the ‘City Forest’, a green space for urban residents which encroached on land that had been used by the peri-urban farmers for fodder, grazing and storage. As fences went up, their access to land disappeared, and pollution also affected the food that was produced for the city.

Read the story: What does the future hold for Delhi’s urban farmers? (Medium.com)

The project highlighted the importance of listening to people who were neglected by urban authorities. In the spaces at the edge of (and between) cities, it can be unclear which agencies are responsible for regulation of pollution, providing public services and infrastructure, and agricultural support. Links between environment, poverty and health go unrecognised. But if they begin to be recognised in planning and policies, then more sustainable urban futures are possible.

The project produced policy briefings and a practical guiding framework to help people recognise important interactions with ecosystems in other rapidly urbanising spaces. We also produced a photo book telling the story of Karhera through images, including photos from archives, showing change over time, with the participation of local residents. Rather than only looking at the perspectives of urban planners and policy makers, it was important to see the perspectives of people who had been farming and living on the land for generations.

Since then, the connections with local activist groups and other diverse stakeholders have grown stronger, and the work continues. One follow-on project is demonstrating the importance of peri-urban agriculture and green spaces, and is developing tools that support new visions for development.

Read more: Two ‘storymaps’ present research that has followed on from this work, mapping how land use is changing in peri-urban areas of large cities.

Mapping green infrastructure in Ghaziabad

Maps and charts showing changes in land use over time and the impacts of plans and developments.Strategies for peri-urban green infrastructure development

Maps and images of food production and tourism initiatives in the city of Wuhan, China.

Pathways to better water in Gurgaon

From 2017, STEPS research on the urban theme also continued with work in Gurgaon, an urban area of rapid development around 30 km from Delhi. This was one of the research sites of the Pathways Network, an international project that used ‘Transformation Labs’ to find responses to environmental-social problems that were controversial and difficult to resolve.

As a hub for information technology and corporate offices, the city had grown very rapidly as workers moved in. As ever more land became covered with asphalt, water stresses quickly became a problem: the city was depleting the water table faster than it was recharging. Construction projects were illegally extracting ground water, and basic amenities became stressed.

The project aimed to create ‘transformative spaces’ where these problems could be discussed by people with different insights and perspectives on the problem. The process included focus group discussions with marginalised groups, workshops with diverse participants, meetings with workers’ organisations, public consultations and community radio programmes.

Read: Enabling transformations to sustainability: Rethinking urban water management in Gurgaon, India

Book chapter in ‘Transformative Pathways to Sustainability: Learning Across Disciplines, Cultures and Contexts’ (2021), open access

To help get more people and groups involved, the Gurgaon Water Forum was set up as part of the project. The GWF aimed to promote dialogue, advocacy, experimentation, and participation in planning and decision-making. Practical initiatives include waste-water recycling and reuse, and flooding prevention at a local level; a longer project is underway to rehabilitate the main drainage channel in the city.

Central to the Forum’s approach is to bring together people with diverse forms of knowledge: NGOs, academics, workers’ unions, public administrators, and citizens’ groups. Despite this, the water system in Gurgaon will continue to be a huge challenge, and will require many more experiments and long-term engagement, so the work continues.

Find out more

Stories of Change

From 2006-2021, the ESRC STEPS Centre explored pathways to sustainability – showing the important roles that marginalised ideas, knowledge and forms of action could play in responding to complex social, technological and environmental challenges.

In this process, we were involved in many process of change, from local struggles to high-level international debates. These Stories of Change explore some key themes from STEPS work, to share what we learned.