by Cian O’Donovan and Adrian Smith

The maker movement in the UK, and globally, has grown rapidly over recent years. Hundreds of maker spaces, equipped with 3D printers, laser cutters, design software, as well as old-fashioned hand tools, have popped up in cities, towns and on university campuses, potentially promising new forms of re-distributed and community-based manufacturing.

But who gets to be a maker, where does making happen and what gets made? And what is the wider social significance of this phenomenon?

For example, if more people are able to open up technology in these spaces – and contribute to technology development in more varied ways – might the hitherto unquestioned values, interests and assumptions of conventional, commercial technology developers be opened up to greater scrutiny and challenge? How might civic-oriented maker activities contribute to a flourishing innovation democracy (pdf)?

These questions were put to a group of makers and the public during Power to the people, a workshop jointly organised by the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) and London’s Science Museum on Friday 21 October 2016. The event was one of a series of three held at the Science Museum as part of a partnership between the two organisations that aims to engage members of the public in contemporary issues in science, technology and innovation policy.

Power to the people aimed to connect making to a broader agenda about rethinking the processes of innovation and democratising technology. Our research into makerspaces at SPRU (pdf) and within the STEPS Centre has been part of a wider set of studies into grassroots innovation, and analysis into the possibilities and limitations these activities hold for redistributing design and innovation capabilities in societies.

The workshop consisted of three parts: a series of short introductory talks, live exhibits and demonstrations of made objects and tools, and a set of loosely structured discussions.

The Lucas Plan

First we heard from Phil Asquith, who discussed his involvement in the Lucas Plan in the 1970s. The Lucas Plan was a visionary agenda pioneered by workers at Lucas Aerospace, who wanted to redirect their manufacturing skills and technical capabilities away from military products and towards socially useful production.

The initiative galvanized a movement for ‘socially useful production’, which called for greater social control over design and more democratic input to technology developments, and led to the opening of community-based prototyping workshops in London and other cities in the UK in the early 1980s.

Maker spaces now

Next, Tom Lynch gave an overview of the contemporary maker community in the UK and showcased his Twitter-connected split-flap display project. Tom presented maker spaces as places in which to meet up, to share ideas, where it’s “OK to be a geek”.

Although Tom painted a picture of rapid growth in the number of makerspaces in the UK, he also offered a critical account: these spaces are often under-representative of women, some socio-ethnic groups and people with disabilities. Whilst diversity was recognised as an issue, Tom pointed out how it can sometimes be eclipsed by the more immediate pressures of finding and funding the physical space to run a community makerspace, especially in cities like London where property prices can be prohibitive.

Exhibits: hacking and repair

Our exhibitors displayed materials, equipment and made objects in order to engage the audience in what happens in makerspaces and maker (and fixer – see below) communities. Raj Shah, Deborah Adkins and Oisin Shaw were from Imperial College Advanced Hackspace, a lab specially constructed as “a new way to prototype” for students and researchers at the university.

Participants dissect a laptop. Photo: Cian O’Donovan

In contrast, Ugo Vallauri discussed the Restart Project. Their mission: “to help people learn to repair their own electronics in community events and in workplaces, and speak publicly about repair and resilience”. Unlike the team from Imperial, Restart don’t have a permanent space, instead they take the tools and skills for fixing and repair out to community centres throughout the UK and beyond, hosting “Restart Parties” where they help people fix technology such as laptops, blenders and audio speakers.

Also in the room were Mark and Alix Bizet from Remakery, and who were exhibiting decorative objects and garments. Amongst these were objects made deliberately to provoke people into thinking about materials and manufacture processes. Clothes made from human hair, for example, prompted varied responses and opened discussion about issues of global trade in hair for extensions, and the exploitation of women and children in that trade.

Remakery also brought beautiful handicraft objects that celebrated making. The mix illustrated some of the aims at Remakery in promoting activities for participants to consider the provenance and value of materials, and become involved in remaking in positive new ways.

Reactions

So what did the workshop participants make of this? What happens when people who don’t normally have a say in technology and production get their hands on it?

Roundtable conversations were wide-ranging and led off in fascinating directions: whether about the political economy of supporting redistributed making and technology activity, and the universal basic income in particular; or the challenges of enrolling community support in these practises; to the low levels of technological knowledge amongst many MPs but conversely, the willingness of some politicians to visit and become associated with the creativity and entrepreneurship in maker spaces.

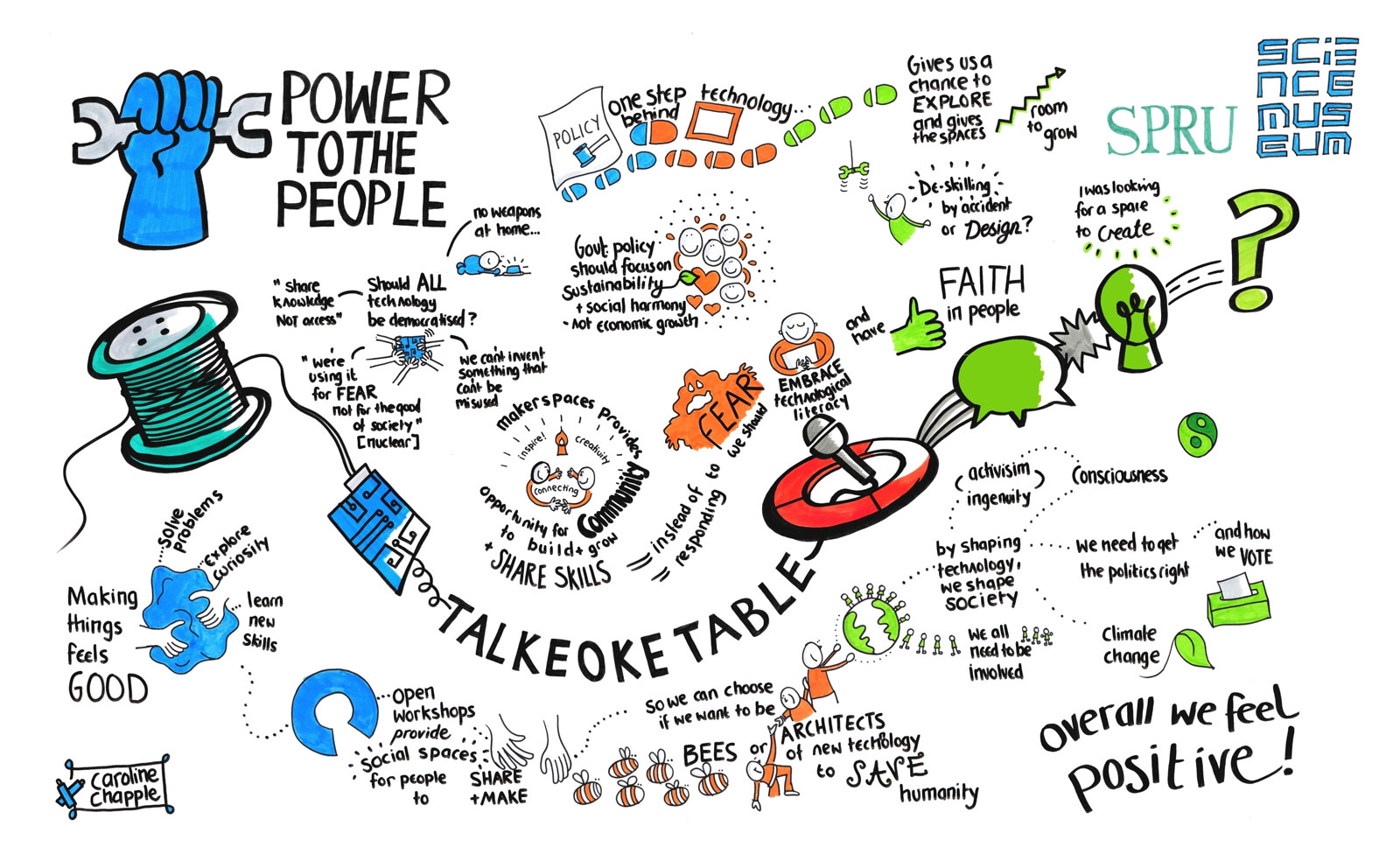

A graphic recording of the event by Caroline Chapple. (Click the picture for full size)

A number of participants questioned the logic of contemporary government spending on weapons, such as the Trident missile programme. When prompted, several disparate views of technology democracy emerged. There were multiple understandings of democracy and technology, perhaps a spectrum, which ranged from democracy meaning direct control by people, to people knowing about the technology and contributing to public debate, to having a say in the creation and deployment of new technologies by others. The debates at Lucas Aerospace appear as alive today as ever.

Tellingly, many participants felt they had little power to influence policy processes on science, technology and innovation, and that even elite “policy is one step behind the technology”. This observation prompted an interesting discussion on whether and how makers might contribute future orientations and directions for technologies; whether through emergent inventions and innovations on the one hand, or encounters with existing technologies such as encryption on the other.

Indeed, the point was made that not everyone needs to innovate in a maker space, value is realised not necessarily from ‘the profound’, but rather though exposing local publics to technology issues, and including more people in a conversation about the ways that technology developers (wherever they are distributed) have a responsibility for the way they shape our lives in positive and negative ways.

Critical conversations

It is tempting to try and construct a neat narrative concerning makerspaces, and indeed, that is the kind of packaging that policy-makers seek. But in reality the issues and discussions are found to be plural and messy, as those at our event demonstrated.

This workshop showed us first that opening up space can in itself be generative of (second) not only new material objects, but also critical conversations, new experiences and ways of thinking and relating, and which in turn will be productive for more open cultures for debating technology.

If the question of ‘who gets a say’ was tricky, issues of the space where these encounters and interactions take place were no less so. This of course was a solitary evening event, but nevertheless offered a lesson for what happens when spaces for deliberating technology are opened up and brought to people. Whilst we were focused around makerspaces, we also reflected that this pertains to other spaces too, such as the Science Museum itself. Issues of access and the availability of different fora in society are prescient.

As Phil Asquith illustrated, Lucas workers in the 1970s were able to turn to their trades union movement and its organisations for support, they had groups, research labs, and other institutional and physical resources behind them. Today, city authorities in Barcelona, São Paolo and elsewhere recognise and support makerspaces because they see them as public infrastructure for twenty-first century technology societies, and in ways analogous to public libraries and knowledge in the twentieth century. Libraries around the globe are now hosting makerspaces. Yet in the UK we’re closing libraries, while many galleries and other social spaces are feeling the strain of reduced funding, particularly at local government level.

In addition to constraints on the availability of physical space required to host these events, access to the people, resources and legitimacy required to organise events at locations such as the Science Museum is also unevenly distributed. As researchers at SPRU, we have privileged access, for which we are grateful. Others with high levels of access include large sponsors — who seek through partnership to legitimise their own technologies – as well as universities like Sussex and Imperial.

At the other points along an access spectrum are community organisations, individual makers, or maker spaces and members of the public. Clearly, then, not everyone has equal access to spaces for deliberating technology. This in itself leads to further questions of who gets to participate in these new spaces of innovation and processes of democratisation.

About the authors

Cian O’Donovan is a researcher at the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU).

Adrian Smith is professor of technology and society at SPRU and a member of the STEPS Centre.

Comments are closed.