By Fiona Marshall and Ritu Priya, STEPS Urbanisation theme

Urban areas are intense meeting points of people and cultures, but they’re also places where more or less visible interactions happen: between the infrastructures and systems of water, energy, food and other resources. These connections pose a big challenge for how researchers understand cities – but they throw up opportunities too.

Urban researchers and planners increasingly look at the ‘nexuses’ between different things in the urban space. For example, producing food and making sure people can buy it relies on water, energy and transport systems working well; if you reduce the quality of or access to one of these things, the others will suffer. These are also underpinned by social and economic systems, arrangements of land, urban planning, engineering, and architecture; and shaped by politics, power and social movements. Because of this variety, urban researchers increasingly need to work with other disciplines and make new alliances.

A recent workshop on the ‘nexuses of the urban’, convened by the Nexus Network, explored how these transdisciplinary alliances could understand and work for urban sustainability. Many of the themes are very much in tune with a conference on sustainable urbanization we held in Delhi in January of this year.

Despite the interest in the ‘nexus’ from policy makers, some kinds of connections are more obvious and recognized than others. In our research, focusing on South Asian cities, we have found that the ‘water-food-energy nexus’ is itself linked to at least four other dimensions – waste, land use, vulnerability and livelihoods, with health spanning all. Many important urban decisions affect not just one, but many parts of the nexus: for example, choosing to reduce landfill by building a waste-to-energy plant can undermine the livelihoods of wastepickers, as well as adding to local air pollution. But the environmental and health consequences are often not anticipated or recognized.

Engines of growth

Contemporary cities in south Asia are being promoted as engines of economic growth. Huge investments in infrastructure are often based on imported technologies and systems that have been deemed successful in entirely different contexts. The suitability and quality of the infrastructure, and social and geographical access to it, have enormous implications for social and environmental justice and for long term environmental integrity.

As cities strive to compete as ‘world class’, an increasing number of policies and plans come under a banner of ‘greening of cities’, developing ‘sustainable resource management’ plans or making ‘resilient’ urban infrastructures. But these initiatives are often skewed to benefit certain groups over others, or exclude some people altogether. There can also be unintended environmental consequences.

Examples of such projects are:

- green spaces that provide leisure facilities for the rich, but can displace or exclude the poor. These include initiatives such as ‘city forests’, which can use large amounts of land and water to establish new tree species, whilst displacing urban and peri-urban farmers. This land could alternatively be used for city farms, working in ways that have multiple environmental and health benefits.

- projects aimed at ‘resilient’ cities (eg attempting to secure the urban supply of water, or fresh urban produce in the context of uncertain climate events, price volatility and other expected shocks and stresses). These plans seem to disengage with nature (and the rural-urban continuum) and take little account of the need for resilient urban communities as the foundation of resilient cities.

Our research has looked how initiatives such as these might be recast to contribute to enhanced environmental integrity and social justice.

Opening up alternatives

To examine alternatives, we need to ask how and why urban policies are adopted and carried out. Over the past few years, our research has looked at why particular mainstream technological interventions, which are presented as improvements to basic service provision or the environmental management of cities (eg waste management, water supply and food systems) were chosen, how they are unfolding and what their implications are in terms of environmental integrity and social justice.

Often the picture for poor communities can be bleak: from unreliable and poor quality water, to losses of land and housing, as commercial interests are prioritized over social equity.

In many cases, there are pro-poor alternatives. Pursuing them means looking at the complex relationships between poverty, equality and environmental management and environmental sustainability. It also means asking why alternative visions for managing urban service provision and environmental improvement are often sidelined. In India, through a series of STEPS and related initiatives we have worked with diverse stakeholders (including poor peri-urban farming communities, waste pickers, local and national NGOs, and government institutes).

Policy change

There is no single reason why urban policies disadvantage poor communities and create environmental problems. At multiple levels of the policy process, there are drivers, dynamics, politics and power relations which influence the setting of agendas and the winners and losers that emerge as dominant development pathways unfold.

So to raise the profile of possible alternative pathways for urban water and waste management, and most recently urban agriculture, we have worked with local partners in Delhi who are highly experienced in policy advocacy. Our involvement is only part of long-running debates and efforts to get a better deal for Delhi’s poorer citizens, whose huge contributions to the city’s economy and life are often underestimated.

Our aim now is to move from ‘appreciating’ alternative pathways to actively building pathways to sustainability. This means exploring how sustainability transformations could take place in cities and the mechanisms through which they can they be realised. We are focusing our attention on how environmental research, undertaken with poor communities, is able to influence sustainability transformations. We will also explore how to achieve a wider systemic change through engagement with urban social movements.

Delhi: how elite agendas create environmental injustice

Currently, urban environmental plans and policies in India are being heavily influenced or captured by elite agendas. They often ignore the links between environmental change, and the health and livelihoods of citizens across the urban-rural continuum. Many mainstream urban environmental management interventions have ‘hidden’ impacts on ecosystems and health, undermining the potential for profound sustainability transformations.

A series of interventions in Delhi over the years have temporarily shifted pollution hazards to the margins of the city and to the poor, but with multiple unforeseen impacts.

- In the early 1970s, the movement of poorer communities out of the city centre, into slums in the periphery, led to a widespread cholera outbreak.

- In the 1990s, small-scale polluting industries were moved outwards to the city margins, resulting in pollution flowing back to the wider urban population in food and water.

- Now, urban farmers are being displaced on the basis of their ‘polluting’ activity without regard for the major causes of pollution or the wider benefits of urban agriculture.

These kinds of environmental injustice could be partly addressed by deeper, sustained knowledge exchange between researchers and communities of the poor. These interactions provide the insights, reflection, real time evaluation and the basis for community empowerment and political leverage that are crucial to urban sustainability transformations as a whole. We believe that there is real potential for wider systemic change if such coalitions can work with wider social movements in India.

We are looking at the sorts of alliances which will bridge the gap between the current focus of elite environmental movements and hidden nexus challenges being faced by communities of the urban and peri-urban poor. We are concerned with how to facilitate learning across different forms of knowledge, and create a political space to address the adverse consequences of urban policies for environment and health.

Going global

Beyond Delhi and its surroundings, we are seeking a deeper understanding of the politics involved in opening up and closing down alternative pathways for transformations worldwide. For the STEPS urbanization theme, we particularly want to know how urban actors can form coalitions for pursuing these pathways (across the blurred boundaries between systems). We will examine the types of knowledge co-production (between formal and informal, researchers and grassroots organizations, elite actors and social movements), how they emerge, are sustained, and what knowledge politics are they subject to.

We have a firm foundation for this work in South Asia and some excellent entry points into topical policy debates.Work by the hubs in the STEPS global consortium also provides some fantastic opportunities for comparative perspectives. We are extending our networks through multiple routes – eg the establishment of a ‘friends of sustainability network’ in south Asia (largely involving civil society groups and academics working together, with a focus on sustainable urbanization); and exciting links with a group working at Arizona State University and Mexico city on similar challenges of coalition building to realise pathways to sustainability for urban water.

Find out more

Browse our Hot Topic on urbanization to learn more about STEPS projects and resources on this theme.

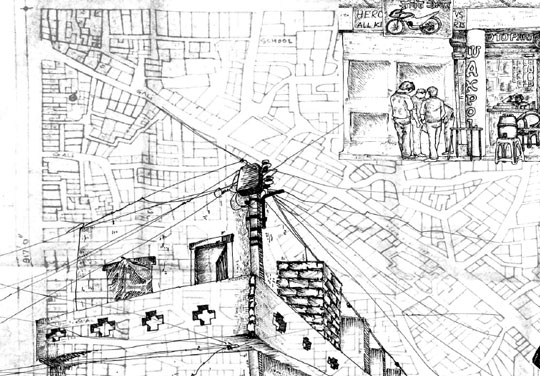

Main image: Illustration from the Water Cookbook by Bhagwati Prasad (STEPS Centre/Sarai)

I tend to agree.