This week marks the 60th anniversary of the Bandung conference when Asian and African countries gathered in Indonesia to discuss independence, peace and prosperity. The conference resulted in 10 principles based on friendship, solidarity and cooperation in this newly post-colonial era for many of the states involved, prefiguring what many now term ‘South-South’ cooperation in development.

China played a key role in the conference and President Xi Jinping is attending the Bandung commemorative summit following his visit to Pakistan.

This makes it an appropriate week for IDS colleagues and I to have been in Beijing meeting with existing and new partners to discuss the roles of cooperation and to debate shared agendas in what is now a very different era of global development.

Changing China

China has long grappled with some of the key problems of development. Amidst extraordinary economic growth and dynamism since the ‘opening up’ reforms 30 years ago, there have been massive advances in infrastructure, finance, industrial and technological change, and urbanisation, and some impressive domestic achievements in tackling poverty and building effective health and social welfare systems.

The sheer scale of China’s changes in a country of such size and diversity – along with its experience of managing complexity and dynamism, and particular combination of central state agenda-setting and local government and market innovation – have long invited international interest in Chinese lessons for development.

Two more recent shifts vastly magnify the relevance of Chinese comparisons and cooperation.

First is China’s growing global orientation, positioning itself as a world leader in addressing shared, interconnected development challenges as ‘first among equals’ of the so-called ‘rising power’ countries. This builds on longstanding Chinese interests in international trade and exports, and recent generations of infrastructure and agriculture projects, especially in Africa.

Now however China is the world’s largest exporter of capital. The country is staking stronger and positive positions in global governance, whether around climate change, international finance or epidemics – with plans to establish a Chinese Center for Disease control in Africa in the wake of the Ebola crisis, for example. The high-profile ‘One Road, One Belt’ strategy focuses on the Asian countries bordering the Silk Road and China’s maritime neighbours, including the recent establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

The second is China’s ‘New Normal’. Now heard everywhere, this term – though uses vary – both describes a situation where economic growth has slowed to around 7% per year or less, and promotes a new paradigm emphasising quality of life, poverty elimination, protecting the vulnerable, and care for the environment.

Chiming with the slogan ‘ecological civilisation’, this signals a stronger commitment to ‘greenisation’ to tackle the environmental consequences of rapid growth and urbanisation – experienced most viscerally in the extreme air pollution experienced by the residents of Beijing and other major cities. In the New Normal, it seems, domestic development is to be sustainable development.

Flows of money, flows of knowledge

How these shifts will play out in practice amidst China’s complex internal and external relations remains to be seen. But what is clear is that these changing flows of money and investment will be accompanied by changing flows of knowledge and learning.The New Normal places a premium on innovation to tackle sustainable development challenges.

As was clear in the rich discussions at the conference on ‘Pathways to Sustainability in a Changing China’ hosted by the STEPS Centre and partners at Beijing Normal University this week, China’s multiple innovation pathways in areas like low-carbon energy, seeds and agriculture, health service provision and sustainable cities can both enrich and draw from experiences in other countries. This event launched the China Hub of the STEPS Global Pathways to Sustainability Consortium, which we hope will facilitate joint research, learning and policy engagement in coming years with other Hubs in Argentina, East Africa and India as well as the US and Europe.

Mutual learning was also the key theme of our launch event for the Centre for Rising Powers and Global Development. This brought top Chinese researchers and policymakers together with the Centre’s other international partners in a roundtable to showcase ideas around global governance and finance, and development co-operation in areas such as agriculture, health and social policy.

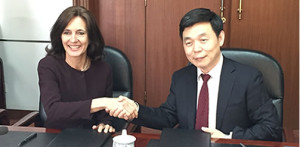

The Development Research Center (DRC) of the Chinese State Council, previously focused on domestic development, is now emphasizing international cooperation and is establishing a China International Knowledge of Development Centre (CIKD) to inform this, as well as a Silk Road Think Tank network. As the DRC head, Cheng Guoqiang, put it, they are interested in internationalizing Chinese experiences, and domesticating international experiences to assist development within China. The Memorandum of Understanding that IDS signed with the DRC should position us to work with partners in help to shape this learning agenda as it unfolds over coming years.

Challenging knowledge and power relations

All this signals that ‘South-South’ co-operation has become something quite different – involving new players and power relations, and a global conception of development, involving shared global challenges and public goods, and progressive change and transformation for everyone everywhere.

This applies to the UK too – development is now as relevant in Brighton as it is in Beijing, Bandung or Bamako.

Yet embracing the opportunities of multi-way innovation and learning in this global context will also require a new humility amongst all countries and institutions – to abandon hierarchies of knowledge and power; be prepared to share and adapt development models, not just export them; and to think seriously about addressing global challenges while respecting diverse local needs and perspectives.

How to achieve this shift – in China or other rising powers, or indeed in the UK – is perhaps the biggest challenge of all, and should be a question on all our minds as we enter this heady new global development era.

- This article was originally posted on the IDS website

- Image: IDS Director Melissa Leach and DRC Director General, Department for International Cooperation and Secretary General, Academic Committee Cheng Guoqiang shake hands, as part of the signing of an MOU between IDS and DRC. Credit: H.Corbett – IDS