by Almendra Cremaschi and Rebecca Shelton, Pathways Network

In the context of climate change and the rise of research about and towards transformations to sustainability, being an early career researcher has huge potential for learning and praxis but at the same time is filled with challenges and questions.

New and deeper ways of reflecting and connecting both with each other and the world are needed, as well as conversations about political, methodological, and other forms of rigor.

To explore these questions together, the ‘Living Aulas’ research school was held over 4 days in Colombia in June. It was designed as a space for learning, sharing, connecting and reflecting among early career researchers.

Living Aulas (Aula translates in English as ‘classroom’ or ‘lecture’) emerged from a collaboration between early career researchers in each of the three ‘Transformative Knowledge Networks’ (Pathways, T-learning, and Acknowl-EJ), who seek to connect transformative research and researchers across theory, methodology, relationships and processes. The group hopes to build a new network as funding for the three existing TKN networks comes to a close in late 2018.

With support from the International Social Science Council (ISSC), Living Aulas involved fifteen early career researchers, activists, and researcher-activists from around the world (South Africa, USA, Argentina, India, Malawi, Colombia, and Spain). The diversity of this group strengthened the discussions around how to merge praxis and research. Together we shared methodologies and frameworks from our respective work, such as the Living Spiral Metaphorical Framework (T-Learning) and the Alternatives Transformation Framework.

The Living Spiral Metaphorical Framework

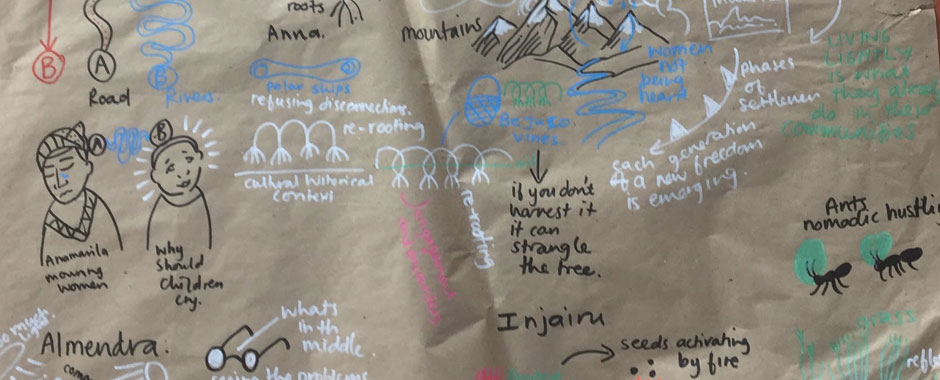

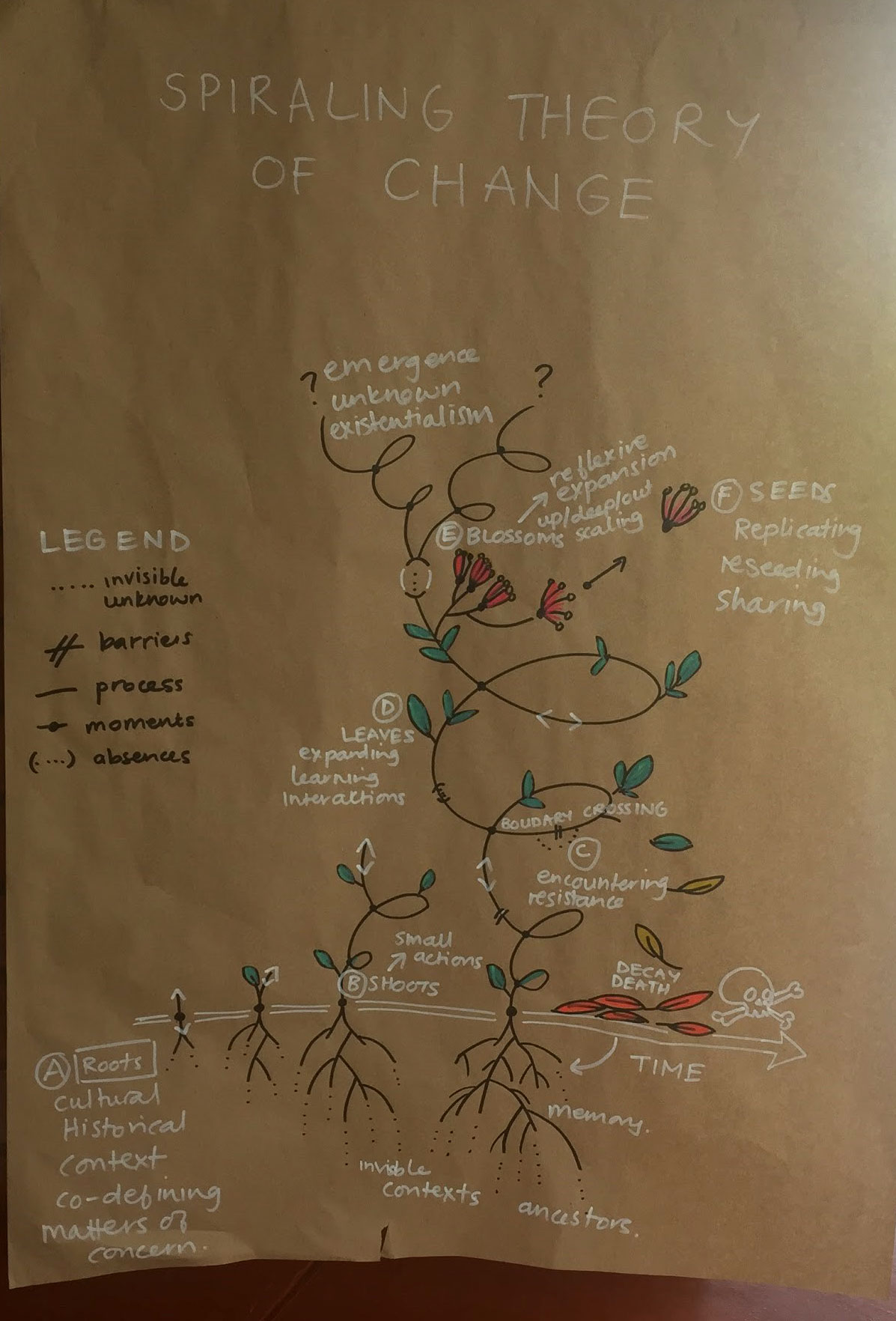

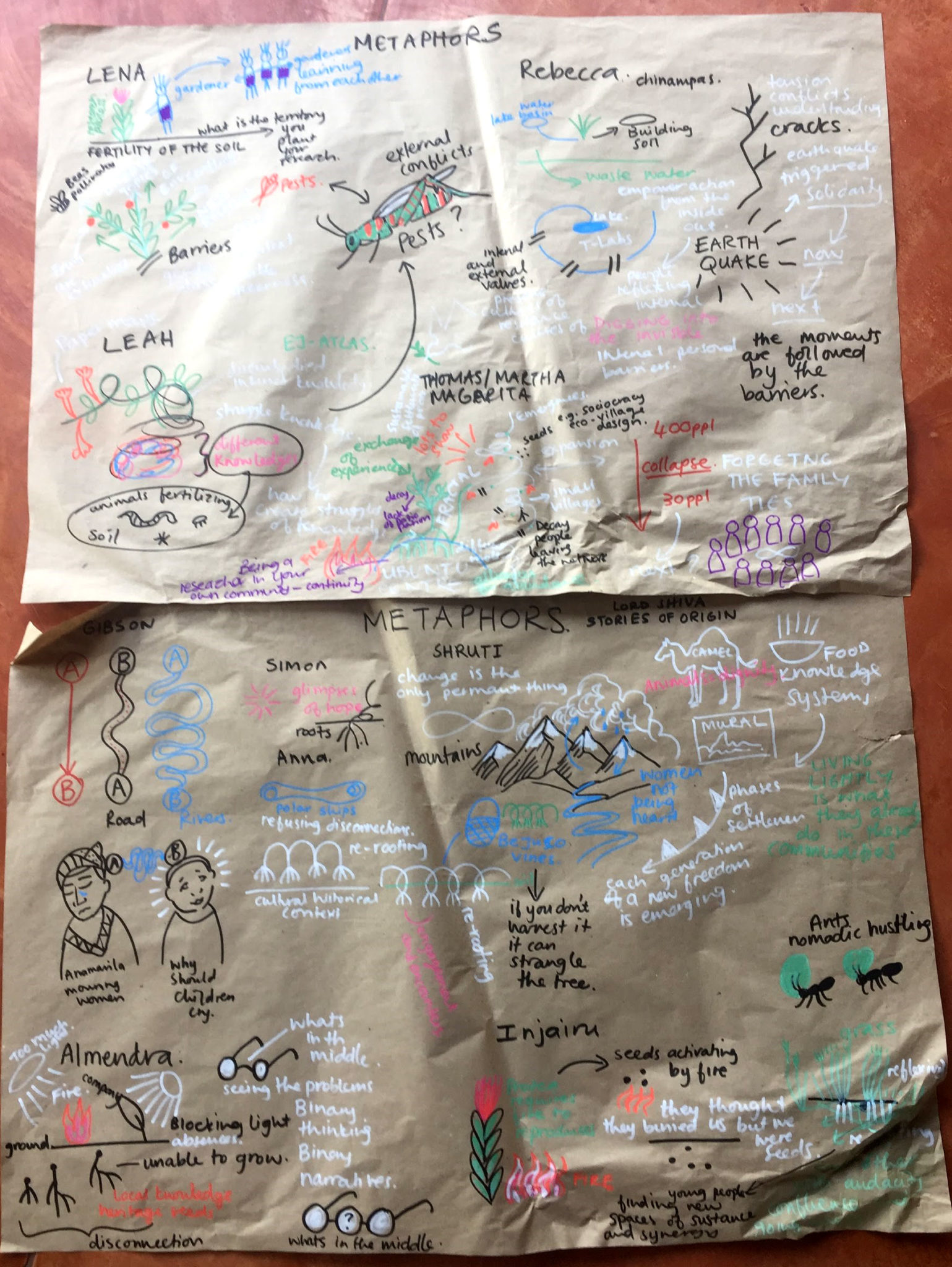

The Living Spiral Metaphorical Framework was an adaptation from the Spiralling theory of Change, and encourages the use of metaphor to aid in understanding how change occurs.

The Spiralling theory of Change was designed by the T-learning team to understand, communicate and analyse change and transformation processes. These processes are shown as structured but “alive”, combining the spiral shape with a plant with roots, stem, shoots, blossoms, seeds etc. Other components can be identified, like barriers; absences; moments of inspiration and comprehension (called “ah-ah” moments); invisible parallel processes, and processes of scaling up, from personal, to communal, to collective transformations.

Mexico: Research and time

The metaphor chosen to describe the T-Lab in Xochimilco, Mexico was the process of constructing a chinampa (the artificial islands used by farmers in the area). To construct a chinampa, you need labor, but you also need time. Time is also critical for our T-Lab process in which we are trying to strengthen collective agency and relationships in Xochimilco.

As we sifted through our own case studies, it gave us an opportunity to reflect on the process as a whole and to see a story of barriers and “ah-ha” moments seated in a dynamic process. We also reflected on invisible processes. And, for Xochimilco, the topic of time surfaced again – the time that participants dedicate to the project and the things that they give up in order to do so often are not clearly ‘seen’ in research.

Argentina: the roots of a new seed initiative

In natural ecosystems, some high, dry grasses block the light that young seedlings need to grow. Natural fires are nature’s way to revive the system, giving light to young plants by burning the old ones, and sending ashes back to the land which then nurture it. This process is repeated cyclically but not identically. This was a useful metaphor for the Pathways Network case in Argentina, which aims to create an open-source licence for seeds.

The case from Argentina finds its roots (context) in the concentration in the seed markets, a process highly intensified by the extension of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) (dry grasses) to vegetable materials. There are several initiatives (seedlings) but they cannot scale up because they are being blocked by the mainstream system.

Our aim is to give light to these initiatives by (a) creating awareness about the challenges of the mainstream system and the potential of more sustainable ways of production, breeding and exchange of seeds (fire) and (b) co-designing social innovations capable of addressing some of the concerns of the current system (shoots). The mainstream system (dry, old grasses) has many elements (nutrients) and kinds of knowledge from which the initiatives (seedlings) can learn. One example of this is the Open Source seeds licence that we have called Bioleft (a blossom), which seeks to protect genetic biodiversity using IPR as an inclusive-defensive tool instead of a restrictive one.

Using the living spiral

We think that this framework has great potential not only to enrich the analysis of each case individually, but also to make a cross analysis of different cases. Despite the great diversity of territories, issues and stakeholders of the cases, we found some similarities both in metaphors and challenges.

Injairu Kulundu (T-learning) also used the metaphor of fire to explain her case. Seeds of the South African protea flower can only germinate when exposed to fire and smoke. She said that in South Africa, the change drivers are like those seeds – activated by the fire and smoke of recent social unrest. They have been stifled for so long and now they are coming up like the forlorn seeds of a protea. The fire, in turn, burns down other plants that have been dominating the terrain for too long to make space for the new protea seeds to grow into healthy plants. There, the drivers of change are asserting the need for more space which will help them to flourish.

What about the barriers to change? Researchers from Argentina and South Africa both identified the problem of ‘polarization’. There is a severe water crisis in Cape Town, and different strategies need to be considered. However, there is a polarization in how people understand the problem, and therefore how they think it can be solved (and who can solve it). While some sectors say it is a natural scarcity and that every drop of water must be saved, others see it as a longer, persistent problem, which relates to unequal access.

One of the cases, shared by a T-learning colleague working in India, had an initial barrier in common with the Xochimilco case study. This barrier was that of overcoming the ‘researcher role’. When researchers or academics come into a participatory setting, they are often expected to fulfil a particular role – that of a researcher extracting knowledge, or having something in particular – something already defined – to offer.

As researchers of sustainability, we often are not coming into contexts with a clear idea of the problem or possible solutions, but come to work alongside others. How many others have faced the same barrier?

What makes an alternative ‘transformative’?

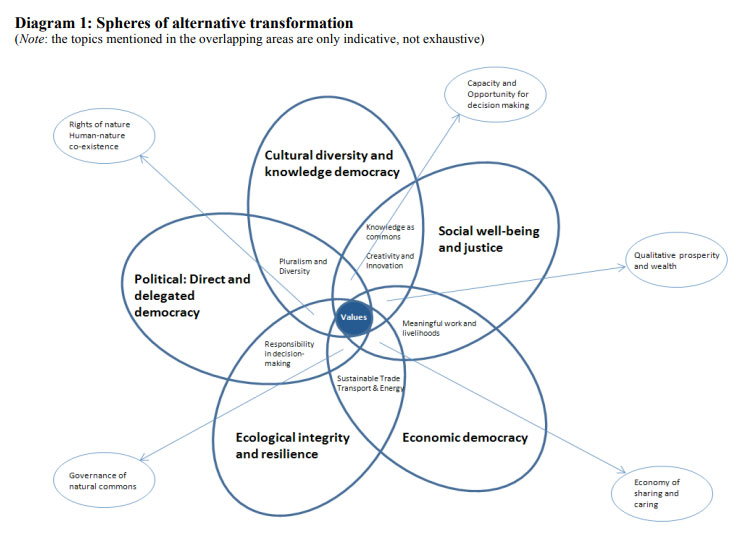

For any given problem, there are different kinds of alternatives and ways to classify them. Some are considered transformative, because they do not address the symptoms of a problem but the cause, such as through challenging power structures. Solutions for symptoms are then called ‘reformist.’

The Acknowl-EJ Alternatives Framework is a tool to deepen our understanding of what makes an alternative ‘transformative’. Why is it transformative? How? And in what ways could it continue to become more transformative?

The Acknowl-EJ Alternatives Framework is a tool to deepen our understanding of what makes an alternative ‘transformative’. Why is it transformative? How? And in what ways could it continue to become more transformative?

However, Acknowl-EJ explicitly explains that the framework is not to be used to “judge” an alternative, especially not by outsiders looking in. It is a tool to be used as a reflexive device for those who are creating, considering, or working towards alternatives in a specific context.

We used the tool to explore alternatives proposed in our own places of work. It may be that a solution cannot ever stand alone as objectively ‘transformative or not’, but must be viewed in the context of where it’s coming from. For example, a community-owned cooperative may not be transformative in the context of some societies, but if you take a society in which extractive industries have held the power for 150 years, and workers have had only their labor to sell – in this case, the values, commitment, and ownership that a cooperative entails may be transformative.

Rituals as a way of ‘transgressing’ techniques

Throughout the Living Aulas, we were also invited, through local culture, practice, and the generosity of the Colombian team, to connect with the beautiful place of Colombia and with each other through ancestral rituals.

These rituals were not meant to be cultural or novel experiences, but were used to generate spaces of reflection and collective decision, as they were originally intended by those who created them centuries ago (and who still use them today). This was a way of embodying the dialogue between different kinds of knowledges, turning to local rituals to reflect on academic knowledges and take decisions related to our future as a network.

The Living Aulas thus reflected the processes that we intend to facilitate in our transformative work. Our work creates spaces that are not organized or enacted through a strict agenda, exact pedagogy or methodological process, but guided by cycles of doing something, reflecting on what has been done, and collective intention.

Building the network

We often say that transformation commonly begins from a place of individual transformation, and from there collective transformation can emerge. We think that through strengthening personal (rather than just institutional) relationships, we can build a network that will continue for many years to come. The Living Aulas was a space not only to connect our research, but to connect with one another on a personal level.

We also found that there is a great value in being able to work within such a diverse networks as Pathways, T-learning and Acknowl-EJ are, but during this collective process we identified a strong need to weaken the boundaries of what distinguishes each of the three TKN and begin to understand the links that exist between our work. Case studies within each of the three networks can be strengthened and better understood by using the lenses of analysis and synthesis from all three networks. But to do that, it is necessary to transgress barriers that block communication, such as language barriers and jargon.

We have confirmed our commitment to build a network of early-career researchers across the three TKNs as a way to integrate frameworks, cosmo-visions/worldviews, and methods. According to Robinson (2008), when science is problem-based, integrative, interactive, emergent, reflexive, and also involves strong forms of collaboration and partnership, it can be defined as Undisciplinary, because it crosses the boundaries of disciplines and includes not only scholars but also non-scholars.

Reflecting on the process that has taken place during the first two weeks of June, we can affirm that we have started our walk together towards an ‘undisciplinary’ network.

References & links

- Alternatives Transformation Format: A Process for Self-Assessment and Facilitation towards Radical Change

- Haider, J. et al (2017). The undisciplinary journey: early-career perspectives in sustainability science, Sustainability Science 13:1

- Kulundu, I. (2018) Moving Through Methodologies: Fostering Decolonial Sensibilities In Our Own Rite(s) (T-learning website)

- Macintyre, T. (2018) A spiraling network of sustainability: Debates, power relations, and tensions in the CASA network (T-learning website)

- Robinson, J. (2008) Being Undisciplined: Some Transgressions and Intersection in Academia and Beyond.

- Shelton, R. (2017) How Rethinking local people´s agency could help navigate Xochimilco´s troubled waters (STEPS Centre blog)

- Van Zwanenberg, P. and Marin, A. (2018) Bioleft: experimenting with open source seed innovation in Argentina (STEPS Centre blog)