By Annie Wilkinson, post doctorate researcher, Institute of Development Studies

As the worst Ebola epidemic on record shows no signs of abating in West Africa, fear and ignorance are increasingly said to be playing a role in its continued spread. Meanwhile, local practices such as the consumption of bushmeat and deforestation are the go-to explanations for the epidemic’s underlying causes. However, decades of anthropological research in the region by STEPS Centre and Institute of Development Studies (IDS) researchers, indicates not only that this picture is an over-simplification, but that disease control policies based on these ideas may be unhelpful.

The latest news from West Africa is troubling: outreach and surveillance officers have been attacked, rumours circulate that the disease does not exist, that medical staff are harvesting organs and anyone going to hospital will not come out alive. Tear gas was reportedly used to disperse a crowd at Sierra Leone’s Kenema Government Hospital who were demanding the release of family members admitted to the Ebola treatment centre there. As many as 57 patients are reported “missing” in the country, either fleeing treatment centres or avoiding them altogether. This seriously hinders contact tracing and infection control efforts.

Both the Sierra Leonean and Liberian presidents have said anyone obstructing suspected Ebola patients from receiving official treatment will be punished. But these announcements are unlikely to have much effect, being disengaged from the reasons behind the community suspicion and the complexities of the socio-cultural context.

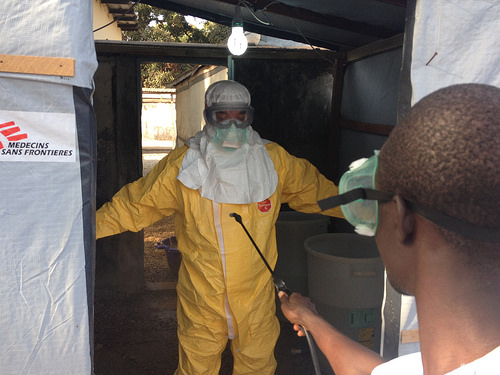

An important lesson from early outbreaks in Central Africa was to include anthropologists in the response teams so that local knowledge could be used to strengthen control measures and minimise fear. Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF) have been using anthropologists as part of their team in this current episode too, but the rumours are proving hard to beat. IDS Director and STEPS Centre former Director Professor Melissa Leach, has lived and worked in the region. MSF recently asked for her anthropological insights, so we at IDS and the STEPS Centre have been thinking about how to put the disease and responses to it in context.

Disease and health seeking

Even the most remote rural populations should not be assumed to be unfamiliar with concepts of modern medicine, however their engagement with them may be mediated by other logics. People are accepting of Western medicine but are ambivalent about the formal health system. The history of Lassa fever, another viral haemorrhagic disease which has been recognised as endemic in the area for decades, is relevant. During my doctoral research on Lassa fever I was told of longstanding rumours about medical staff administering lethal injections. Patients have been known to avoid the Lassa ward in Kenema.

Underlying health seeking patterns, is the fact that people hold multiple models for interpreting and responding to sickness. In Mende areas, there are general categories of big and small fever, and ordinary and hospital sick, as well as specific biomedical diseases. Lassa was classified a ‘big fever’ and Ebola may well be too. Diseases can be understood as caused by multiple things, including germ theory or ‘witchcraft’. These causes are not necessarily mutually exclusive. A diagnostic test which ‘proves’ someone has an illness may not be viewed as conclusive. Key to understanding health seeking is to understand how disease categories shift as the illness progresses. The way people and those around them have behaved, the events leading up to the illness and circumstances surrounding its onset all influence the model which is applied and the treatment sought.

Death and ‘secret’ knowledge

Traditional burial practices have been implicated in transmission as they involve mourners having contact with the deceased infectious body. The importance of burial practices cannot be underestimated as they are strictly controlled by the male and female societies (known as ‘secret societies’ in English) who are central to local and regional politics. Medical teams wishing to prevent traditional burials will likely be intervening in domains of power and ‘secret’ knowledge that lie at the heart of the socio-political fabric which society officials control.

Secret knowledge, and membership of particular societies which offer access to that knowledge (to different degrees) characterises this region of West Africa. Much about the medical response may resonate with these themes: hiding patients behind screens (in isolation), wearing masks (protective clothing). It may be that medical teams are interpreted as another ‘secret society’. Response teams should be sensitive to these possibilities and aware of their why they may face resistance.

As with disease, there are multiple kinds and causes of death. Certain circumstances – such as sudden death or that of a pregnant woman – raise suspicion. ‘Witchcraft’ is the most frequently discussed but this confuses some distinct phenomena including malicious spirits, bad intent by sorcerers, and inappropriate behaviour. If a death is blamed on ‘witchcraft’ it is necessary to establish which of these three is thought to be at work as they will be dealt with differently. Such deaths may require special practices and again secret knowledge is likely to be important. This may be an additional reason why funerals are proving a flashpoint in this epidemic. It is possible that by not allowing the secret societies to carry out the appropriate cleansing after unusual deaths that medical teams are perceived to be making the situation worse.

Avoiding simple explanations: the need for social science

While the recognition of Ebola in the area is new, people are likely to be interpreting and responding to it in line with longstanding local frameworks. Public behaviours and attitudes that might at first sight appear to reflect ignorance, can and should be seen as part of cultural logics that make sense given regional history, social institutions and experience.

Viewing conflicts as stemming from opposing categories of traditional and modern does not capture the complex and emergent meanings which define life in this region and this epidemic. This blog highlights only a small part of this, but it illustrates the need for a social science perspective. That perspective should also include examining the politics of knowledge which are at play. Simple narratives that blame the epidemic on local people for eating bushmeat and deforestation are already appearing. Prof. Leach has highlighted how these overlook well established patterns of land use and interaction with bat habits and so are unlikely to explain why the disease has emerged in West Africa now.

It is hard to say much with great certainty about Ebola, except that it is terrifying and tragic for those affected; all the more need for researchers, health workers, policy makers and the media to be cognisant of the power and politics involved in responding to and controlling the disease.

Find out more:

- Hot Topic: Zoonoses and the truth about Ebola

- Ebola in Guinea – people, patterns and puzzles Melissa Leach, Lancet Global Health blog

- Tackling the Ebola epidemic in west Africa: why we need a holistic approach Naomi Marks, The Guardian

- Haemorrhagic Fevers in Africa: Narratives, Politics and Pathways of Disease and Response STEPS Working Paper by Melissa Leach

- The book Epidemics: Science, Governance and Social Justice includes a chapter on Ebola and Lassa fever.

- Dynamic Drivers of Disease in Africa Consortium

Comments are closed.