by Hallie Eakin, Lakshmi Charli-Joseph and J. Mario Siqueiros

In our PATHWAYS network case in Xochimilco, Mexico City, we are exploring whether people can have ‘agency’ to make a difference to very complex socio-ecological problems. Xochimilco is a degraded but very culturally, ecologically and economically meaningful wetland system in the south of Mexico City.

In a recent project workshop, we turned our attention on to ourselves. Given our focus on ‘agency’, what can we say about our own agency as researchers involved in what we hope will be transformative research?

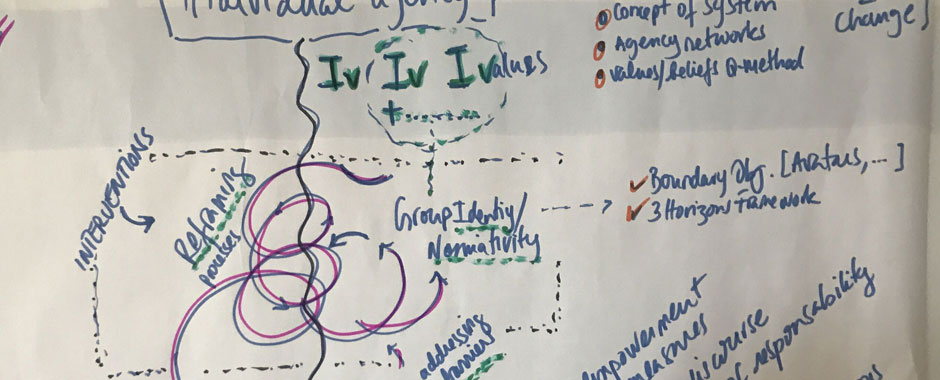

Agency, simply put, is power to act with intention. We are all agents: we have unique identities, we can and do take concrete action on our own behalf, and we do so with specific ideas about what is important, valuable, and meaningful. Across the PATHWAYS network, we’ve found that there are a diversity of perspectives, roles, institutional constraints and opportunities, and contextual issues that affect how we see our own agency and what we do about it. Inevitably these play into how we situate ourselves in the work that we are doing. The PATHWAYS network has allowed all of us to reflect on where we stand in relation to communities and individuals; sustainability and justice issues; and the institutions and political-economic contexts of our work

The North America hub is a diverse but small team, composed of three researchers from Arizona State University (ASU) and three from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Those of us from ASU are physically distant: our engagement is episodic and we are clearly outsiders. Our ‘stake’ in the issues at hand is intellectual, and it’s also personal to the extent that we are able to empathise with people in Xochimilco, and are concerned about the humanitarian and ecological consequences of what is occurring. But we are foreigners; while we can acknowledge the iconic cultural and ecological value of the wetland system, it is not our culture. Those of us from UNAM are much closer to it and therefore our engagement with each participant is deeper: we communicate with the actors on a weekly basis, and have developed relationships that go beyond the initial scope of the project.

How do Universities constrain the agency of researchers?

The immediate institutional contexts in which we are working also affect our agency in the project. We are fortunate that both our affiliated institutes at ASU and UNAM have embraced engaged, transdisciplinary research. Nevertheless, our institute tend to implicitly favor our roles of knowledge brokers, conveners and facilitators of learning over more action-oriented and interventionist work.

And within each institution, we are all at different stages in our careers. Those of us who are ‘junior faculty’ are concerned about how our work is measured and evaluated by our institutions, and perhaps have less flexibility to challenge university norms of practice and engagement, and less capacity to devote significant energy to highly risky activities that might not result in any tangible outcomes. The students involved in the project in both institutions also have to define a “researchable project” with research questions, methods and results that would be observable in the timeframe of two or so years.

Advocating solutions or facilitating agency?

In the particular case of the North American Hub, we were clear that we were not advocates of a particular solution or pathway. In any case, most of the ‘solutions’ proposed in the past have been unsuccessful. We believe that this may have been due to a lack of real participation of the people who both depended on the wetland and were having a real direct impact on its evolution: the farmers, households in informal settlements, and residents within the wetland system. We wanted to engage with those populations and explore with them how to develop a collective sense of agency that could then be mobilized in novel ways—ways we had yet to imagine.

So, in this work, we clearly positioned ourselves as facilitators and conveners in which our stake was more in whether the process we designed would help facilitate agency, rather than in producing a specific action or pathway of change. In any case, agency is a prerequisite for deliberate change and for the creation of purposeful pathways to sustainability.

Our decisions still mattered, however. Implicitly, by deciding to engage with particular individuals in the process, we were privileging their voices, perspectives and agendas in any broader process of change occurring in Xochimilco.

Alternative theories of change

All of these issues come to the fore when we are engaged in a process in which we hope to observe seeds of transformation. Whose transformation? To what ends?

If, in the Xochimilco case, the activities we conduct in collaboration with farmers, residents and activists in the wetland system do not appear to be leading to a new form of collective agency, have we failed in our research design? Or should we be prepared to shift our design, and do more intensive partnering and intervening ourselves, in terms of proposing interventions, and pressuring individuals to do more than they volunteer to do? Or, as we have learned from the experience of other groups in our network, perhaps partnering with an ‘implementing’ agency – a willing NGO, activist group or network – is essential. Yet in the North American Hub’s activities, this would have meant aligning our initiative with the agenda of an established organization. Given that we were attempting to facilitate a new perspective on the problems at hand, which could lead to novel strategies for change, this did not seem appropriate.

At this stage in our process we have no definitive answers to these questions. It is clear, as our colleagues in Delhi have stated, that the researcher must also be transformed to conduct transformative research. We are all at different stages in that process, and while it is fraught with questions, it is ultimately one of the more rewarding learning experiences in our collective endeavor.