By Annie Wilkinson, post doctorate researcher, Institute of Development Studies

(This post is part of a series of reflections emerging from a workshop on complex adaptive systems research methods held in Baltimore in June 2014.)

At the recent workshop on methods for complex adaptive systems (CAS) research in Baltimore, jointly organised by the STEPS Centre and Future Health Systems (FHS), thoughts turned to the legacy of such long-term programmes. Though they had different funders, both STEPS and FHS started in 2006. So now, as both programmes start thinking about their 10th anniversaries, how can we begin to summarise all that research and the influence that it has had?

If stuck in a lift with a DFID minister, for example, what would we say?

Memory fail aside, the question is hard to answer because our consortia have made it a mission to embrace the complex realities of health systems and other development contexts, and summing up needs to go beyond what is recorded in journal articles and research reports.

In a small-group discussion as part of the workshop, we concluded that one of the most innovative features of the FHS consortium is that we have developed and utilised approaches that put people and contexts at the centre of research.

The learning involved in doing research in messy and changing contexts is as important an outcome as the project findings. We have experimented with a number of tools to explore complexity in our research settings, many of which were discussed at the CAS workshop and are described in this blog series. But, in summing up our research, we need tools that enable us to explore the dynamic interactions between the context and the intervention, and the learning that this had generated over time. One such tool is the innovation history method, already employed across a number of STEPS Centre projects, and which the FHS Bangladesh and the FHS India teams have recently adopted.

About innovation histories

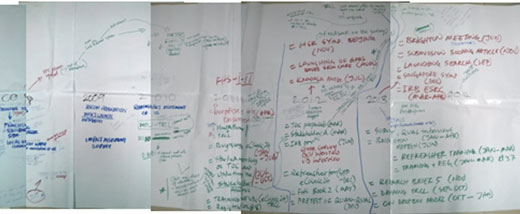

An innovation history, developed by the International Centre for Tropical Agriculture, is a participatory method for developing a detailed timeline and description of an innovation – in this case the design and implementation of a research project. Key elements are timeline construction, stakeholder mapping and production of a shared narrative history. Based on an understanding of innovation processes as evolutionary and non-linear, it traces how multiple innovation pathways emerge from the project and asks who are the people and events which shape them.

Innovation in Bangladesh?

I worked with the FHS Bangladesh team to carry out an innovation history and found it to be a productive and rewarding experience. It is not often that one is given a chance to reflect on the past and to be open and honest about what happened. What makes an innovation history different is that is tries to get beyond, or beneath, the official version of events, to probe the informal and the personal. It takes a while for people to warm up – and to remember! – but asking people about their experiences and opinions can bring about some fascinating insights.

The Bangladesh team have experienced some difficulties in the implementation of their mHealth project. A private-sector partner pulled out abruptly and uptake was not as high as hoped. Standard evaluations might have labelled this a failure. However, the innovation history highlighted what has been gained from this, and previous experiences with FHS research interventions in Bangladesh.

That history is one of continuous engagement and network building with informal providers and most recently with mHealth actors. From this base, the team have found – and continue to find – creative ways to deal with unexpected events and to keep up with the fast paced growth in Bangladesh’s eHealth sector. By taking matters into their own hands, for instance developing their own mHealth platforms when their partner pulled out, they have strengthened their in house capabilities; by seeking partnership and interactions with other eHealth players, they have positioned themselves at the centre of the emerging innovation system. All the while, they have maintained their focus on the people of Chakaria and are well positioned to take any innovative solutions to scale.

(For another STEPS example, the newly-established STEPS methods site includes a description of how innovation histories were used in a project on low-carbon development in Africa.)

Reflections on the innovation history process

Adapting to the context by developing one’s own capacities, reviewing old assumptions and creating new networks is surely an appropriate – and resilient – way to deal with the uncertainty and complexity of innovation and health system contexts.

If a focus of FHS research has been people and complex contexts then innovation histories are great ways to sum this up. As a tool they push us to pay attention to the experiences of people involved and to get beyond successes and failures, to see what has emerged over long periods of time. In its approach and its findings the innovation history in Bangladesh is an example of how FHS has supplemented RCT style evidence generation by putting into practice ways of opening up and broadening out health systems research.