by Yang Lichao, Kennedy Liti Mbeva and Jiang Chulin

This blog post summarises discussions between the Africa and China hubs at the project-wide meeting of the PATHWAYS Network in Dundee in August 2017.

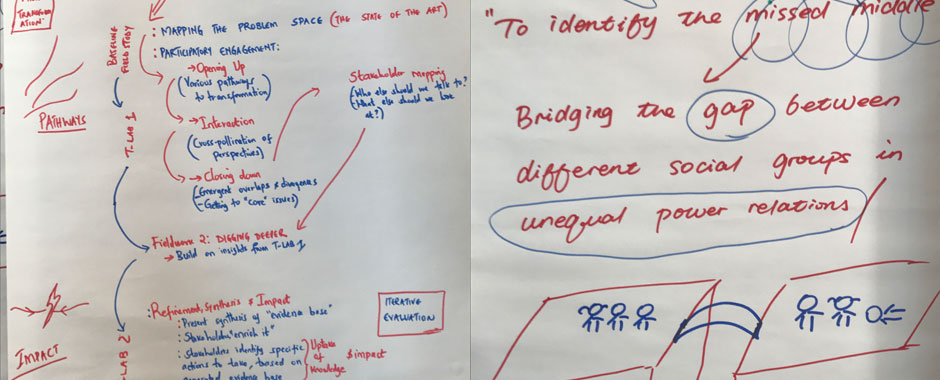

The Africa and China hubs in the project are both working on ‘Transformation Lab’ (T-Lab) processes related to energy, climate change and industrial production. In Africa, the hub is exploring the opportunities and barriers for pro-poor, low carbon energy from Solar Home Systems in Kenya. In China, the hub is exploring how the rapid decommissioning of cement factories in Hebei Province has affected local workers, and how the country’s ‘green’ agenda could take better account of these impacts. In both countries, we are exploring how transdisciplinary research can help empower local people to pursue transformations that benefit from a range of different people’s insights and learning.

In the project, the Africa and China hubs are a ‘pair’ of hubs committed to ‘co-learning’ throughout the project. This has included exchange visits from the Africa hub to the China hub, and vice versa, to discuss working practices and share emerging insights. These exchange visits have been crucial for encouraging a feeling of togetherness and a sense that the members of each hub are all part of a bigger team.

At our meeting in August, when all the hubs were gathered together, we discussed the ‘co-learning’ process between Kenya and China and what we had discovered.

These included some general insights and shared commitments:

- We see our role in transformation as producing knowledge and building the capacity of other experts, to inform policy and provide insights that cross national boundaries.

- It’s important to learn from indigenous knowledge and appreciate local voices. If the academic knowledge produced ‘borrows’ from indigenous knowledge, then it must respect local perspectives and seek to ‘broker’ knowledge between different groups who may have very different ways of seeing the world. We see this kind of ‘brokering’ of knowledge as fundamental to sustainability transformations.

- There are always diverse stakeholders in processes of transformation, but academic and research institutions have a unique ability to synthesize the different perspectives. This is especially true in developing countries where there are many initiatives addressing similar issues.

How does transformation happen in Kenya and China?

We also identified common challenges in carrying out T-labs. For example, we have both found that it is very challenging to track the impacts of the two T-labs and evaluate them in a comparative way. It is also hard to identify the extent and nature of change over the short life of a project. These challenges apply as much in Kenya as in China, but for different reasons – one of which is how complex policy change actually happens in both countries.

To explain this, we can look at the important differences in how pathways to sustainability can be pursued in Kenya and China.

In Kenya, transformations are driven by both government and actor networks, which can collaborate or come into conflict in different ways and at different times. For example, in our study of the case of domestic solar power, there are strong networks of businesses, researchers and funders promoting distributed solar home systems – but with a mixed response from government, which prefers to invest in more centralized energy production, despite its climate commitments. So an important way forward may be to highlight the points of contention and try to identify where state and non-state actors could work together, with the help of technology, investment, and knowledge brokers.

By contrast, in China, it is largely impossible for transformations to be driven by actor networks in this sense: the policy process is mainly top-down and authoritarian in nature. This can be seen in the swift closures of cement plants, as part of an agenda to cut pollution – as workers suddenly lost their livelihoods, with little opportunity to retrain or diversify. Voices of workers and other parts of civil society were absent from the decision-making process. Our strategy has been to show government officials the impacts of these closures on workers, by bringing them face to face in a workshop as part of our ‘T-Lab’ process to hear stories from those affected. This kind of process may go some way to helping to avoid some unintentional harms of China’s policy of ‘ecological civilisation’.

Who is involved in transformation?

We have also found striking similarities and differences in the roles and significance of different players in the transformation process in both countries.

In Kenya, government-led transformations in the energy sector are mainly driven by the economic case for change: that is, seeking the most cost-effective intervention to reach the largest number of people at scale. Environmental and social aspects are secondary. Other actors, especially civil society organisations, have a different focus – for example, placing emphasis on the broader context of poverty alleviation.

In China, marketization has prevailed since the 1980s – a radical change from the traditional values underpinning Chinese society. The pursuit of market and economic benefits have overwhelmed decision-making and public life. The resulting environmental degradation and pollution has become a serious challenge, and a crisis that can no longer be ignored. But it is the government that will determine any large-scale response; other stakeholders, like those in civil society, play a much less important role in policy-making than in Kenya.

We feel that we still have lots of things to learn and experience together. We look forward to our co-learning journey in the following year.

Very interesting article that is sending the massage to the world: There is a need for new types of frameworks for urban governance if we are to develop sustainable societies. This explains why there is also a need for cities to learn from each other. It adds more value on the growing field of knowledge of co-creating sustainable solutions. There could be a contrast in the approach: top-down/Bottom-up. But the essence is that in both cases there is need to apply the Quadrupple Helix approach, leaving no one behind in developing shared visions.