Making stuff is all the rage these days. But how does sustainable development fit into this enthusiasm?

The White House is celebrating a Week of Making from June 16-23 2016 after hosting its first Maker Faire in 2014 to spark a “grassroots renaissance in American making and manufacturing”. The hope is that by exposing people to design and fabrication skills it will “unleash a new era of jobs and entrepreneurialism in manufacturing and transform industries”. This follows the first ever EU Institutional Maker Faire, European Maker week, which ran from 30 May 2016 to 5 June to celebrate “makers and innovators from all over Europe”. The 400 events across the continent ranged from workshops on 3D printing in Italy to learning how to use a machine to do controlled cutting of hard materials, like composite or wood, in Limerick, Ireland. In February this year, there were also government-supported events to celebrate making in India. The maker movement is both mainstreaming and globalising.

A key element in the maker movement is the growth in makerspaces. These community-oriented workshops are equipped with freely-accessible tools, traditional and digital, such that people can get involved, meet and share resources and knowledge and to build and make things. There is an ethos of sharing designs, instructions and ideas, and making them available to the ‘commons’ through open source principles. Do-it-yourself and communal making spaces have expanded in popularity over the past decade – there are 14 times as many maker spaces as there were a decade ago. The scene is diverse, ranging from grassroots hackspaces to institutionally supported FabLabs.

With their rise in popularity, could these makerspaces help support sustainable development and have a social purpose? There are some exciting examples to point to. POC21, an “innovation camp” held in 2015, aimed to “overcome the destructive consumer culture and make open-source, sustainable products the new normal” by bringing together scientists, makers, designers, “geeks” and engineers to develop prototypes for a fossil free society. Some of the open source prototypes – that is, designs which are publicly accessible, and can be modified and shared – that came out of the camp included: reusable, 3D-printed water filters; a solar power concentrator; a portable solar power generator; and a wind turbine that costs less than £21 to build.

Of longer standing is Fablab Amersfoort, which aims to be a sustainable lab, working with recycling materials. And the Open Source Circular Economy Days consciously supports sustainable developments, by promoting initiatives and discussion in makerspaces as well as in the movement more widely.

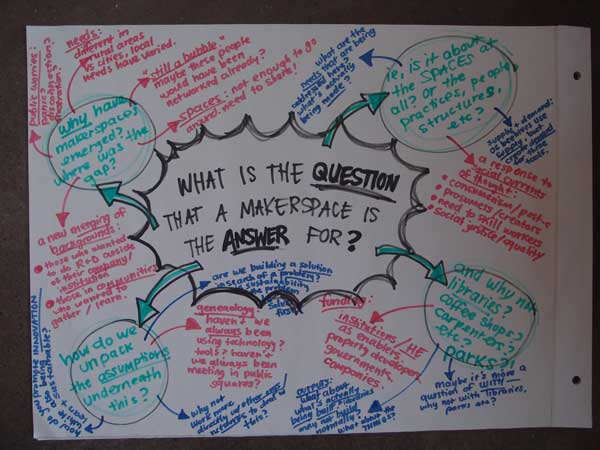

While these makerspaces make sustainability a key aim in their work, it’s certainly not a given that they all will. Indeed, concern for social justice and environmental sustainability appears absent from many maker movement activities. Adrian Smith, Professor of Technology and Society at the University of Sussex’s Science Policy Research unit, believes that unless explicit strategies are in place, there is a risk that makerspaces and making will drive consumerism and add to our environmental woes, rather than solving them. He organised a workshop to find out what can be done to boost the sustainable practice out there, and help cultivate sustainable development in makerspaces. The workshops involved leading practitioners in making and fixing for sustainable developments in Europe. The findings from the workshop are summarised in the Box below, and the full report can be found here (PDF). Reading the report, and hearing about the initiatives discussed there, this is what struck me most.

There is no blueprint

Fab Labs, which started out of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA), have a set digital fabrication tools that theoretically allows anyone to make almost anything they like, to innovate and become local entrepreneurs. Fab Labs are located in places as geographically and culturally diverse as Detroit, USA, the largest US city to ever file for bankruptcy, Spain, UK, Norway, Ghana, South Africa and India. In Ghana, for example, villagers built solar energy collectors and made machines to grind cassava into fufu powder, a time-consuming task previously left to women.

While the Fab Labs have been built in ethnically and geographically diverse environments, there is still a lack of ethnic and gender diversity within many makerspaces. There is a risk that the makerspaces will see technology as THE fix. But technology is only one dimension of the local development process said workshop participants. Social purpose could be injected into the movement by investing in community development. The technological skills of facilitators might need to be complemented with community development skills in order to increase participation of wider segments of society. Listening skills might need to be improved too. “Learning to listen to the grassroots is really important… It only works if you listen really carefully and put communities in the driving seat,” Smiths says in this podcast.

Makerspaces could take part in outreach activities acting as social hubs for information, contacts, and action. While there is a risk that this role is at odds with a makerspace’s creative role, some, like The Great Recovery, have created things, such as a recycled and reupholstered sofa, but have combined this ‘making’ with outreach activities on waste and successfully mobilised interest in solutions for more circular economies.

Sustainable pathways

Directing makerspaces along more sustainable “pathways” could potentially contradict the whole open source and free culture, especially in more self-organised hackspaces: “The makerspaces aim to create settings where people can playfully and creatively explore new design and fabrication possibilities….Directing people along certain (sustainability) pathways in makerspaces appears to contradict the cherished spirit of openness and autonomy found in makerspaces,” the conference report says. How can this inherent contradiction be overcome? The report points out that makerspaces operate in a structured world, where class, gender, race and other institutionally reinforced inequalities have to be strategically countered by makerspace organisers, and participation ensured, if those same structures are not to be reproduced in the maker movement.

Technological citizenship

A key trend within the movement is to make the manufactured world more democratic – sometimes referred to as technological citizenship. The Restart Project, which aims to “fix our relationship with electronics” is an example of this. Anyone can bring their broken tea kettle or slow electronic devices at pop-up community “parties”. People are supported by “restarters” who provide technical support and encouragement. The idea is to empower people to repair devices themselves and use the electronics they have for longer and to reduce e-waste. The Restart Project is popular – it claims to have run 185 parties in six countries since 2012. But, significantly, through this activity the aim is also to enhance people’s sense of having a stake in the way products are designed and made, and to exercise a form of technological citizenship in demanding the right to longer-lived, repairable electronics.

The project was inspired by people living in developing countries who “would never think to throw away things – they would repair them and give them a second lease of life” says Ugo Vallauri, co-founder of the Restart project. Having lived in Burkina Faso and Rwanda for three years, I saw this first hand. Every component of a bicycle or car was used and re-used. If it couldn’t be used, it was stored somewhere until it could be re-used in something else. Nothing was thrown away.

While there is no blueprint and it’s still early on in the evolution of makerspaces, the suggestion is clear: we need to move beyond just creating technology labs. Creating more socially-inclusive makerspaces focussed on creating sustainable innovations, could lead to a culture that benefits us all.

Key findings from the workshop report – How to cultivate sustainable developments in makerspaces by Adrian Smith and Ann Light:

|

Read the full report

Makerspaces: creating inclusive spaces for sustainable innovations (PDF)

Comments are closed.