This is one of a series of Stories of Change from the ESRC STEPS Centre.

Our work on science, technology and innovation suggested how these could be shaped in more democratic ways. Insights from grassroots innovation movements show the vital role of relationships, values and shared ideas in innovations that point towards more sustainable futures.

Science, technology and innovation can be crucial to creating prosperity and wellbeing, but there are big assumptions about how they do it. One is that investing in innovation and technology is bound to speed countries towards economic growth as part of a process of modernisation, with benefits trickling down to the poor. Another is that universal solutions to grand challenges can be found, if only they can be ‘scaled up’ in the right way.

Work by the ESRC STEPS Centre has challenged these assumptions. As well as being a force for good, new technology and innovation can bring problems, entrench inequalities, or even be used for violence and oppression. And problems of poverty or conflict rarely have a single cause that can be fixed by technology alone.

This means it’s crucial to think about how decisions are made, who makes them, what values are behind them, what kinds of uncertainties are in play, and how the benefits or risks of innovations are distributed.

Since 2006, STEPS research has explored how citizens can take centre stage in developing science, technology and innovation, and how this might lead to better results.

A ‘new manifesto’ for science, technology and innovation

In 1970, a document called the ‘Sussex Manifesto’, written by a group from the Institute of Development Studies and the Science Policy Research Unit, helped to shape modern thinking on science and technology for development. Forty years on, the STEPS Centre (including researchers from the same institutions) decided to ask what kind of Manifesto was needed for today’s world.

The ‘Innovation, Sustainability, Development: A New Manifesto’ project involved contributions from all STEPS Centre members and a network of international partners. The process included a dedicated series of 13 background papers by STEPS researchers and their colleagues, exploring the history of these ideas and the latest experience on how science, technology and innovation were shaped.

It also aimed to get participation and ideas from a wide range of people and places. This reflected the core idea that science and technology play very different roles in development depending on where you are, and different professions can have radically different views on it.

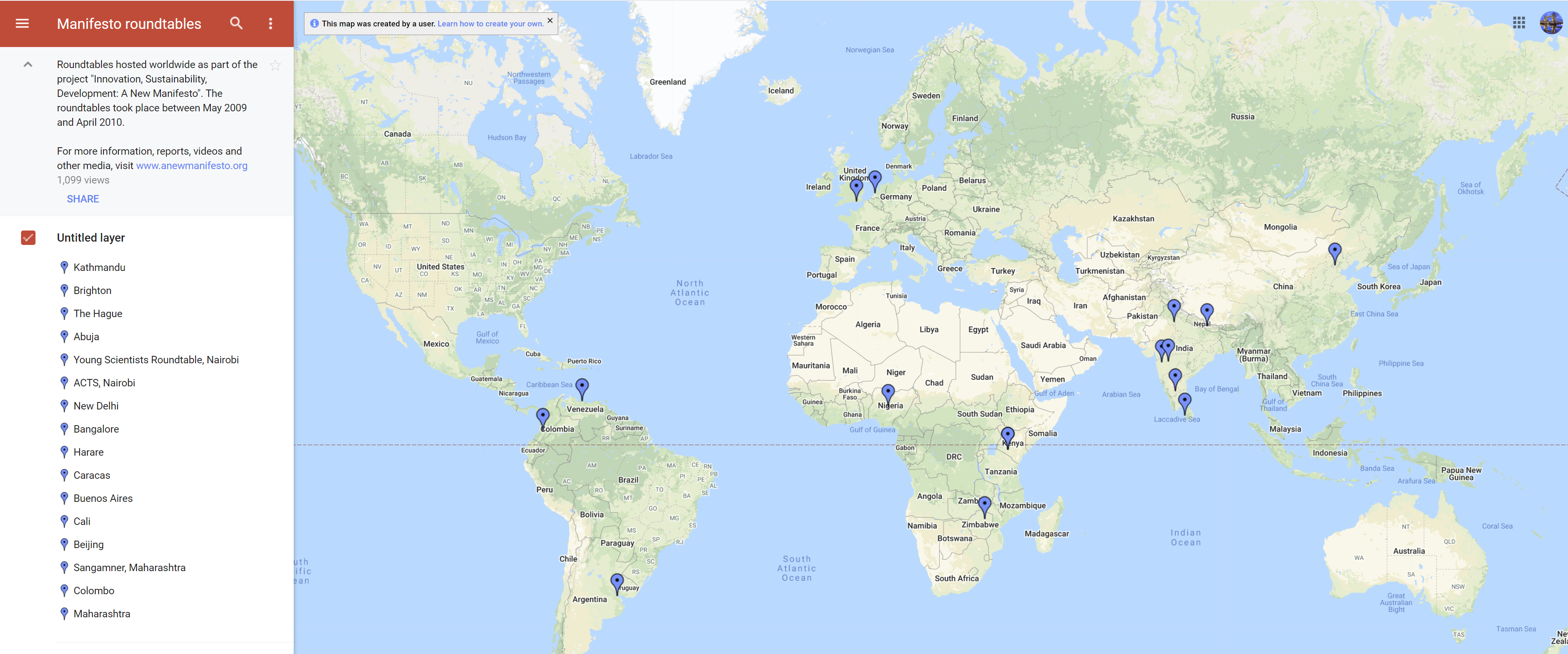

To do this, STEPS ran an international seminar series and 20 roundtables conducted throughout the world — involving hundreds of individuals from women’s groups in rural Maharashtra to researchers in Venezuela to the Zimbabwean Minister of Science and Technology.

View the original interactive map

Our partner in rural India, Marathmoli, reported that women involved in the roundtable had changed their perception of women’s experiential knowledge and science and technology innovation, added value to their work and made them look at their work in a new light.

The project ran other events in Nepal, Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe in collaboration with the development NGO Practical Action and worked with TWAS to engage with young researchers in Kenya and India.

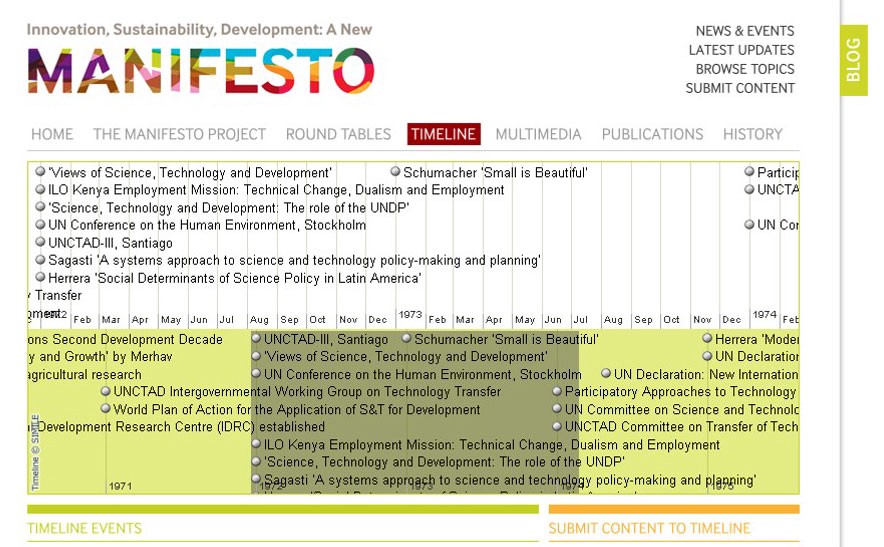

A dedicated website was used to encourage people to engage and document the process. The website included a crowdsourced (‘wiki’) timeline charting key relevant events in history, along with publications and all the multimedia resources we collected, including videos, photos and reports from the global roundtable events.

The New Manifesto proposed a ‘3D agenda’, drawing attention to a set of questions for innovation policy: ‘what is innovation for?’, ‘which kinds of innovation, along which pathways?’ and ‘towards what goals?’ (Direction); ‘who is innovation for?’, ‘whose innovation counts?’ and ‘who gains and who loses?’ (Distribution); and ‘what — and how many — kinds of innovation do we need to address any particular challenge?’ (Diversity).

It also made recommendations around five areas for action (Agenda setting, Funding, Capacity building, Organising, and Monitoring, evaluation & accountability).

In 2010, forty years after the original Sussex Manifesto, the New Manifesto was launched at the Royal Society in London, with a one-day conference involving around 150 people. It was translated into French, Egyptian Arabic, Portuguese, Chinese and Spanish, and reported not only in the UK media but across Europe, China, India, USA, Brazil and Colombia.

The report was also made available as a ‘Multimedia Manifesto’ — an annotated version with links to video and other resources at key points in the text.

The document struck a chord with many, especially as the international community reflected on the Millennium Development Goals and what might follow them after 2015. Outputs from the Manifesto project influenced (and were cited by) UK parliamentary committees on building scientific capacity for development and the post-2015 development goals.

Internationally, STEPS researchers were invited to present the Manifesto at an IDRC-OECD event in Paris in 2009, to UNESCO, the World Social Forum and the World Innovation Forum. STEPS also organised an event at the ESRC Festival of Social Science in Brighton, 2010, aimed at the general public. And in October 2012, the New Manifesto project won the prestigious European Association for the Study of Science and Technology (EASST) Ziman award for “the most innovative cooperation in a venture to promote the public understanding of the social dimensions of science”.

Innovation at the grassroots

The Manifesto had set out to show how citizens could be involved in shaping science, technology and innovation in different places. But was there anything special about innovations started by citizens themselves?

A STEPS project on grassroots innovation set out to understand better how individuals and communities at grassroots level were coming up with solutions for sustainability, and had been doing so for decades. How readily might this on-the-ground experience become the raw material for the more generalised aspirations of the New Manifesto?

Grassroots innovation: historical and comparative perspectives

The project looked at history as well as the present day — from the UK movement for socially useful production in 1976, to modern-day makerspaces and hackspaces, or the Honey Bee Network operating since 1996 in rural India. These groups often involved creating spaces where people could share skills and exchange ideas — more recently, using the internet to communicate.

In particular, the project looked at innovation in India, Latin America and the UK. These three settings were very different, but some common questions applied. For example, what happened when grassroots innovators came face to face with mainstream institutions — lenders, businesses, patent offices and governments? Would this help them ‘scale up’ their ideas, or would they clash or be co-opted? Why did some movements fail and others succeed? Was there anything about grassroots innovation that made it more ‘sustainable’, or was it equally prone to creating wasteful or ephemeral things?

A key insight was that the products — the most visible things or solutions — were only half the story. Communities of makers and hackers create something more than objects: they create things that are less visible, but no less important. These are things like the right to unpack technology, take it apart and understand how it works; a sense of solidarity and community; the sharing of skills and learning; and even new visions of the future. They could provide spaces for people to question how products, from a mobile phone to a new kind of seed, are normally designed and developed.

By its nature, grassroots innovation is very dispersed and diverse, and can’t be fixed or improved by applying a single solution or policy. The STEPS team focused on the principles at the heart of open, democratic innovation. They worked for example with the the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which was exploring how ‘inclusive innovation’ could be scaled up and the Inter-American Development Bank, asking whether digital fabrication could herald a ‘revolution’ in Latin America.

Scaling-up inclusive innovation: asking the right questions?

For these organisations, the insights from the STEPS Centre’s project were challenging. Instead of scaling up, perhaps grassroots innovation could be supported by a more decentralised, ‘scaled-downwards’ approach, as it looks very different in different contexts. And could a technology really be revolutionary without a social ‘revolution’ as well — one that allows people space to deliberate and debate about new technologies?

Work that followed on from the project, showed staff at Colciencias in Colombia how their work connected to wider movements and histories of community innovation. The benefits of supporting this went way beyond the products themselves.

The team also went on to engage with many communities of makers and innovators — from ‘street engineers’ in Argentina, to people involved makerspaces and workshops in the UK, Spain, France and the Netherlands. An event in London with the Centre for Innovation and Energy Demand (CIED) brought together an international group to talk about makerspaces and sustainability, inspiring several blog posts and articles by participants.

Articles in the Guardian about the Lucas Plan and fabrication workshops in Barcelona, plus an appearance by Prof Adrian Smith, the project’s convenor, on national radio in Spain, helped to spread ideas about grassroots innovation to a wider audience, and helped to highlight problems as well as celebrate examples of success. A thinkpiece for Friends of the Earth showed the links between innovation and democracy, and how grassroots innovations could be supported by action on culture, infrastructure, training, investment and the law.

In 2016, a book published by Routledge brought together insights from the project. The findings went on to inform further events and work on open science in Argentina led by STEPS América Latina.

Post-automation

Since then, Adrian Smith has also begin to form networks of thinkers around the idea of post-automation. This explores at how people have repurposed and hacked the technologies of automation for alternative social goals. Post-automation can challenge the sense that automation is an inevitable technological force in society.

Reflecting on the STEPS work on grassroots innovation, we realised that it reveals some questions about how research is often organised and funded, and how it can engage with makers and innovators over time. The networks formed with makers in the project shows the importance of allowing time to build relationships. Many of the most exciting ideas and initiatives in this area are not obvious — they have to be sought out, recommended, explored. This means having room to experiment.

By their nature, grassroots innovations change over time, meaning that a single visit or engagement isn’t always enough to really understand what’s going on. It also takes time to build up trust, so that busy makers will allow time to explain to a researcher what they’re doing.

And it’s not enough for researchers to capture what they’ve discussed into neat or general insights for a journal article — they also ought to feed back their findings to help grassroots innovators reflect on their own practices and learn from what others are doing. As innovators and technologies become more networked, and explore how to confront new problems and challenges, this isn’t the end of the story — it’s the beginning of much longer stories of learning, with more surprises and experiments on the way.

Find out more

Stories of Change

From 2006-2021, the ESRC STEPS Centre explored pathways to sustainability – showing the important roles that marginalised ideas, knowledge and forms of action could play in responding to complex social, technological and environmental challenges.

In this process, we were involved in many process of change, from local struggles to high-level international debates. These Stories of Change explore some key themes from STEPS work, to share what we learned.