36 hours in Venezuela to attend a roundtable: Innovación, Sostenibilidad y Desarrollo para el siglo XXI: una visión desde Venezuela (‘Innovation, Sustainability and Development for the 21st Century: a Vision from Venezuela’), hosted by the Centro de Estudios de la Ciencia del Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Cientificas (IVIC) and Fundacite Miranda (Fundación para el Desarrollo de la Ciencia y la Tecnología en el Estado Miranda), both under the Ministerio del Poder Popular para Ciencia, Tecnología e Industrias Intermedias), with the STEPS Centre, linked to the STEPS Project ‘Innovation, Sustainability, Development: A New Manifesto’.

The roundtable was convened by Drs Iokiñe Rodríguez (Researcher), Hebe Vessuri (Researcher and Director) at IVIC and Francisco Herrera (President, Fundacite Miranda), who divided the group of over 30 participants under 4 themed discussion groups on: Food Security, Sustainable Cities, Socio-Environmental Risk, and New Technologies. There is much I’d like to share about the various discussions at the roundtable that I can’t cover here, but stay tuned as the report by the roundtable convenors will be forthcoming, as well as other related blogs. Following are a few of my own questions and observations, though as a preface, I must say that one day is by no means sufficient to understand the complex political, social reality of Venezuela.

A bit of visual context: To get from the airport located on the Caribbean coast to Caracas the highway passes through a small Northern sample of the Andean mountains, and follows along the edge of the National Park Protected Area, El Ávila. I’d been hearing of the recent droughts (climate change? El Nino effect? ‘normal’ variability?) and the hillside scene was truly brown-grey bone dry with obvious blackened swathes, evidence of fires in various places.

Contiguous to the park, the first signs of approaching Caracas are informal colonization of the steep hillsides by people who have settled in precarious cement brick houses. In places evidence of relocation and rebuilding projects by the Chavez government are visible, standing out in their organised lines of color (often in patriotic red-yellow-blue).

Beyond that fringe, Caracas is also an immense city of high-rise apartments, office buildings, industry, traffic and of course many more people, all of which and whom I only glimpsed as we drove by on the highway, on our way up to another mountain where IVIC perches atop amidst the exquisite landscape – housing some 1500 researchers, plus postgraduate students.

The sign over the highway at the turn-off for IVIC: ‘IVIC – Ciencia para el Pueblo’ (‘Science for the People’) sparks my already piqued curiosity about where politics meets science in Venezuela. I am certain these words are meant to underline the stated priorities of the popular Bolivarian revolution led by President Chavez since 2000. Controversial, radical, a self-proclaimed ‘revolution’.

The sign over the highway at the turn-off for IVIC: ‘IVIC – Ciencia para el Pueblo’ (‘Science for the People’) sparks my already piqued curiosity about where politics meets science in Venezuela. I am certain these words are meant to underline the stated priorities of the popular Bolivarian revolution led by President Chavez since 2000. Controversial, radical, a self-proclaimed ‘revolution’.

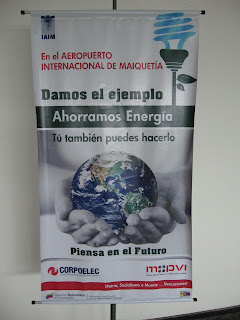

I’ve heard extreme opinions about Venezuela’s ‘transformation’ as represented in international media and in the Venezuelans I’ve met abroad, but have always been wary of what to believe. Just in my taxi ride from the airport to IVIC one rumour was confirmed: petrol here is amazingly cheap – far cheaper than water! To fill a medium-sized car’s gas tank here, I was told it costs less than 50 pence. But all forms of energy are not equal, and energy in the form of electricity is actually scarce at the moment. Venezuela is highly dependent on hydro-electric for its power and the recent dry spells have drained rivers and dams, leading to electricity rationing. Some roundtable participants told me that government campaigns for efficiency have been effective at increasing consciousness about reducing electricity and water consumption – apparently set in the familiar frame of environmental consciousness (see photo).

But as in any society, will this consciousness remain when the crisis passes? Apparently there have been strong protests any time there has been the indication of a rise in petrol prices. I wonder about the incentives – necessity, nationalism, environmentalism, financial cost? And which one (if any) might settle in for the long term?

But as in any society, will this consciousness remain when the crisis passes? Apparently there have been strong protests any time there has been the indication of a rise in petrol prices. I wonder about the incentives – necessity, nationalism, environmentalism, financial cost? And which one (if any) might settle in for the long term?

In the midst of building the new Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela – trying to create a social and political transformation to socialism, where does science and technology fit into the political process? The Chavez government speaks of ‘endogenous development’, uses wealth from petroleum resources to support social programs and reforms, has been vocal in promoting regional solidarity in markets, reforming of school curricula and housing – all with a populist approach, an emphasis on participation by all members of society, especially the most disenfranchised, considered most vulnerable to capitalist models of development. Roundtable participants pointed out that the 3Ds are very much present in the new Science, Technology and Innovation Law of 2001, the Science Mission of 2006 and the new Constitution of 1999, and I am curious about efforts like the ‘Socialist Networks for Productive Innovation’ – Redes Socialistas de Innovacion Productiva). Yet some roundtable participants felt that such efforts haven’t effectively engaged the full scientific community, or that the implementation of policies has been lacking. Furthermore, one roundtable participant argued that while the government has set a target to double crude oil production in the next 3 years the national focus on export of raw materials doesn’t direct needed attention to adding value or building capacities of domestic industry.

At the roundtable I sat in on the ‘Sustainable Cities’ breakout group where participants pointed out that any discussion of sustainability and development needs to pay specific attention to cities, urbanisation, and planning – especially in Venezuela where more than 90% of Venezuelans live in cities, even if the distinction between urban and rural is not always clear in qualitative terms. The point was made for a need to create a vision of a sustainable city– a vision that isn’t present in Caracas now and one that needs to be a wholly Venezuelan vision, not an imported European or North American vision.

Much of the discussion centred around bridging gaps – in terms of communication between disciplines, between the scientific community and policy-makers, and between written policy and implementation, though there was a notable absence of industry (in discussion and representation). And despite some divergent political views there was a truly constructive atmosphere of fruitful dialogue. Across the groups there was a real strong excitement for the space created by the roundtable, a space that was noted for its absence until now and opportunity moving forward. Not only was there interest in creating a vision for a ‘Manifesto’ for Venezuela, but to continue these discussion spaces through different forms as part of the means for creating and then facilitating the implementation of a new agenda for science, technology and innovation for the nation.

Watch this space!